National sovereignty in the climatic age

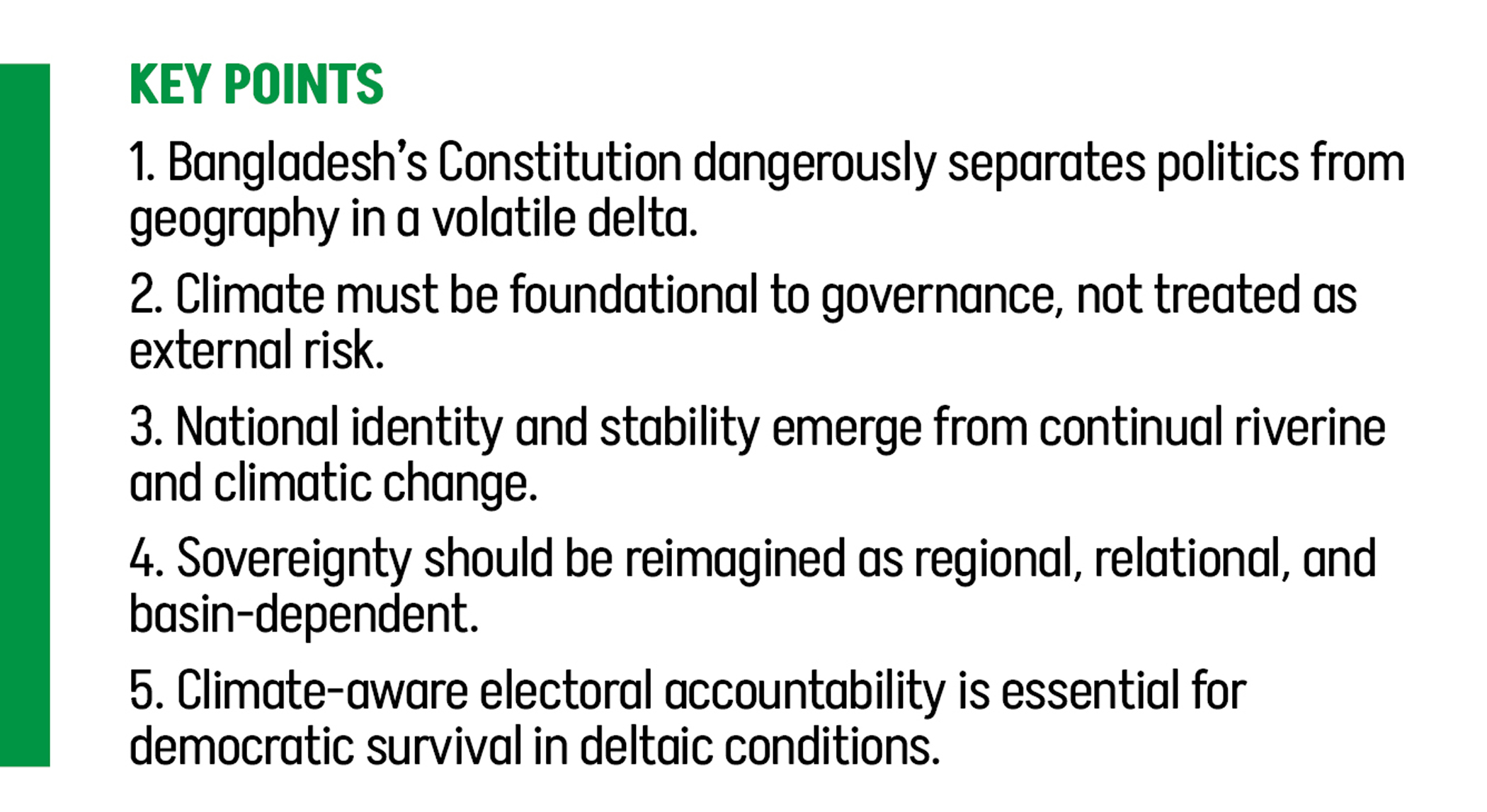

In the recent reform efforts initiated by the interim government, significant attention has been paid to elections, electoral politics, and fundamental rights, yet a critical question remains largely unaddressed: where does geography and the political challenges it produces fit within these reforms? If those tasked with reimagining the constitutional future of Bangladesh believe that geography can be dealt with later, this signals a deeper problem in the prevailing thought of the state. It reflects a worldview that externalises nature, relegating it to the imagined category of the “environment,” something to be managed technically rather than lived politically. This way of thinking assumes that politics can exist independently of climate, as if life in the Bengal Delta allows for a separation between governance and geophysical reality. In the planetary age we inhabit, this assumption is not merely outdated; it is existentially dangerous. The persistent separation of climate from politics only deepens the crisis we face, foreclosing the possibility of a constitution capable of addressing the conditions under which life is lived.

The language through which climate change is addressed in policy and law today largely revolves around protection and adaptation – protecting the environment, protecting communities, protecting development from external shocks – and this language presumes a separation between nature and society, climate and politics, law and land. It treats climate as an external force that occasionally disrupts an otherwise stable social order. In a deltaic country like Bangladesh, this presumption is not only inaccurate; it is actively harmful. Such rhetoric allows climate to become a “tomorrow problem,” something to be dealt with in the future, or an adversity that somehow bypasses the collective “we.” The result is a form of political delay in which climate is always urgent but never foundational, always acknowledged but never decisive. This mismatch is visible not only in everyday speech but also in everyday laws, and in the constitutional imagination itself, which continues to push away ways of negotiating and living with geophysical reality. It is therefore surprising that climate-proofing the Constitution remains absent from reform discussions, not because climate is irrelevant, but because it is assumed to be external.

To move beyond this impasse requires a fundamental shift from protection to alignment, beginning with how the Constitution understands the country itself. Bangladesh is not a nation that exists on stable ground and is then affected by climate change; it is a nation continually made and unmade by climatic and riverine processes. Erosion, sedimentation, floods, salinity, and shifting channels are not exceptional disruptions but the conditions of life. The Brahmaputra–Ganges–Meghna system is not a threat acting upon society but the material infrastructure through which land, livelihoods, and political communities come into being. The idea of “Shonar Bangla” has often been romanticised as a stable ecological past – six seasons, predictable rivers, fertile land – and while this nostalgia is culturally powerful, it is politically paralysing. There is no return to a prior equilibrium. The climate that now shapes Bangladesh is more volatile, more uneven, and more unforgiving than before.

What gives Bangladesh its fertility, density, and cultural richness is not stability but the alluvial process itself: the continual arrival of silt, the constant rearrangement of land and water. A constitution that imagines permanence in such a landscape governs a fiction, and the cost of that fiction is borne through slow violence, displacement, and recurring catastrophe. Recognising this does not diminish national identity; it deepens it. “Shonar Bangla” is not golden because it resists change, but because it is continuously made through change. Constitutional language, especially in the Preamble, can acknowledge that the Republic is founded upon a living delta, where land, livelihoods, and political life are shaped by riverine and climatic processes. Such recognition reorients governance away from emergency response and toward long-term alignment. Erosion becomes not a failure of development but a political condition requiring constitutional planning, while displacement ceases to be an anomaly and instead becomes a recurring reality that citizenship, representation, and rights must anticipate. At this level, climate-proofing protects the Constitution itself, for a constitutional order that ignores the delta eventually undermines its own authority.

This realignment also requires a rethinking of sovereignty, because, like most postcolonial constitutions, Bangladesh’s Constitution inherits a classical nation-state model in which sovereignty is imagined as internally supreme and territorially contained. The State appears all-powerful within its borders, while external relations are framed as matters of diplomacy and choice. For a deltaic country, this model is deeply misleading. Bangladesh’s geophysical existence depends on processes that unfold across the entire South Asian region. Rivers originate far beyond its borders; sediment loads are shaped by upstream dams, diversions, and land use; monsoons, glacial melt, and climate variability operate at continental and global scales. Bangladesh does not merely interact with the region; it is constituted by it.

Treating regional cooperation as merely economic, political, or diplomatic, without grounding it in the realities of life on the delta, is therefore profoundly problematic. It suggests that national policy alone can secure land, water, food, and climate resilience, when in reality many of the most consequential decisions affecting Bangladesh are made upstream or across borders. Climate-proofing the Constitution requires rescaling sovereignty, not abandoning it but reimagining it as relational capacity: the ability to secure national survival through engagement with basin-wide and regional systems. Acknowledging regional embeddedness does not weaken the State; it strengthens its claims by constitutionally grounding demands for shared responsibility, basin-scale governance, and transboundary accountability of rivers, forests, and ecosystems such as the Sundarbans. When regional cooperation is framed merely as foreign policy, failures of cooperation are treated as unfortunate realities; when framed constitutionally, they can be named as political and legal harms. This shift also guards against the false comfort of self-sufficiency, for a Constitution that pretends Bangladesh is geophysically autonomous sets the State up to fail its citizens, sustaining nationalist zeal in the short term while undermining long-term survival.

Finally, without electoral alignment, constitutional climate recognition risks becoming technocratic or judicialised, disconnected from democratic life, even as climate politics cannot remain trapped at the scale of the delta as a whole. The Bengal delta contains immense ecological diversity: coastal zones facing salinity and cyclones, floodplains shaped by seasonal inundation, char lands subject to erosion and accretion, drought-prone northwestern regions, and heat-stressed urban centres. These agroecological zones experience climate differently and therefore require different political responses. Uniform, national-level climate promises blur responsibility and allow contradictory electoral mandates to coexist, where upstream constituencies vote for water retention or extraction and downstream constituencies vote for flood mitigation or sediment flow, both democratically validated yet hydrologically incompatible. The State is then left to reconcile these contradictions administratively, while downstream harms are depoliticised.

Area-specific or zone-specific electoral manifestos offer a way out of this trap by reconnecting votes to material consequences without fragmenting the polity. Candidates would be required to articulate how resource use, water management, infrastructure, and adaptation strategies relate to the specific ecological conditions of their constituencies and how these fit within national and constitutional limits. This does not mean granting constituencies absolute rights over nature; rather, it clarifies that electoral authority over natural resources is conditional. A climate-proofed Constitution can establish that resources are held in trust by the State, to be allocated equitably and sustainably, and that no local mandate can justify disproportionate harm to others. Elections thus become mechanisms for negotiating shares rather than asserting absolutes, enabling voters to demand accountability for protection, adaptation funding, water access, and land security, while representatives are judged on outcomes rather than rhetoric. At a larger scale, political parties must also confront cross-border climate vulnerability and regional redistribution, recognising that climate governance is a distributive political question rather than a moral abstraction.

These three shifts signal the possibility of deltaic alignment, rescaled sovereignty, and climate-aware electoral accountability needing to form a coherent constitutional project. They do not seek to weaken the State, romanticise nature, or fragment democracy, but rather seek to make governance possible under conditions that already exist. Bangladesh has lost the luxury of treating climate as a future problem. The delta is already rearranging land, livelihoods, and political life. A Constitution that continues to imagine stability, autonomy, and uniformity will increasingly govern a country that no longer exists. Climate-proofing the Constitution is not an act of idealism. It is an admission of reality and the minimum condition for democratic survival in a volatile delta.

Dr Saad Quasem is a Lecturer in Anthropology and Climate Change at SOAS, University of London

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details