Will delaying LDC graduation address problems long ignored?

Bangladesh is on the path to graduate from Least Developed Country (LDC) status on 24 November 2026. In 2018, and again in 2021, the country crossed all the required thresholds set by the United Nations, placing it firmly on track to formally exit LDC status in 2026. Few would deny that this achievement reflects five decades of steady progress. Income levels have risen. Health and education outcomes have improved. Export-led manufacturing has transformed the economy in ways that would have seemed improbable in the years following independence.

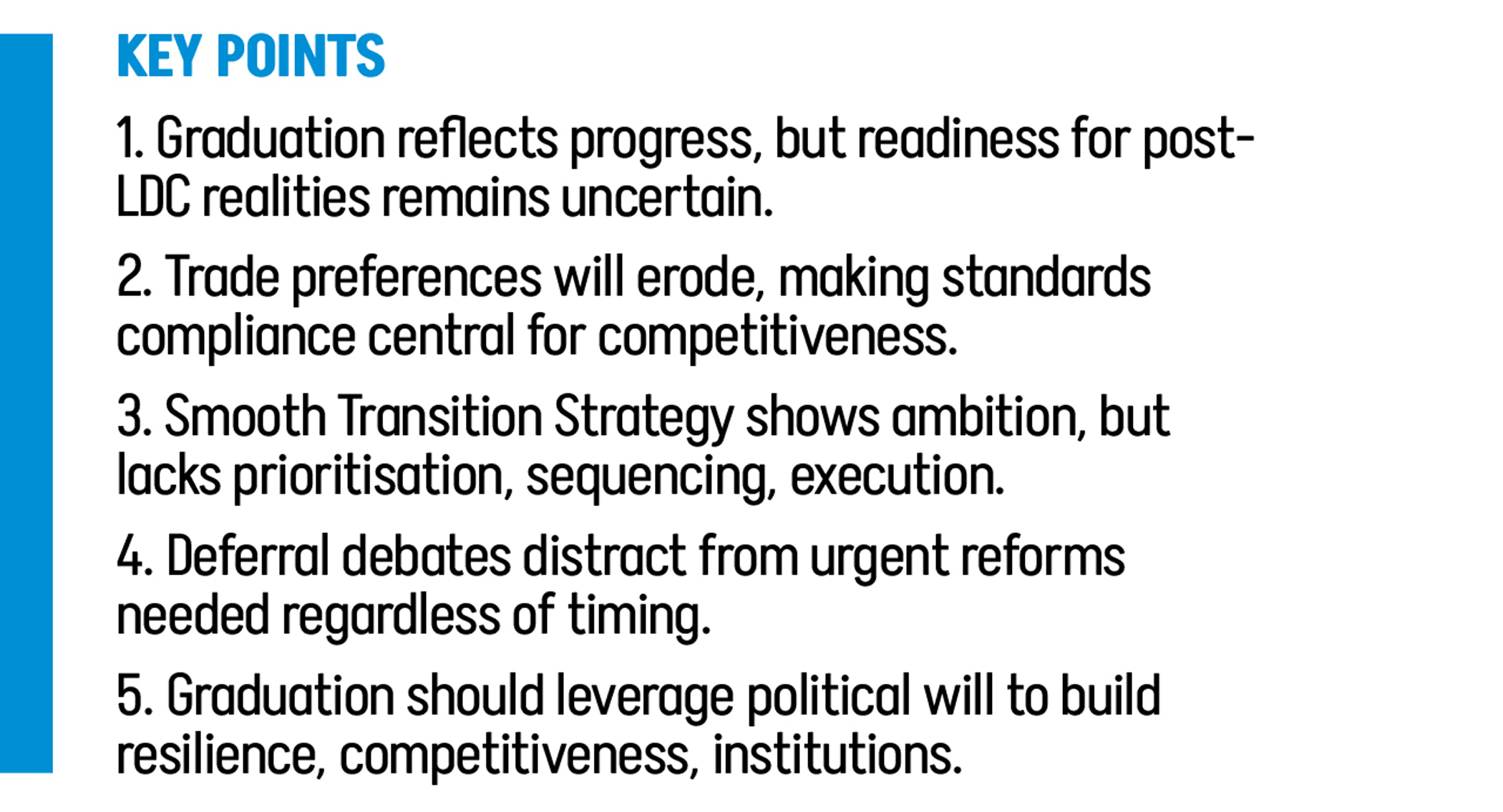

Yet inevitability should not be confused with readiness. Graduation is a milestone, not a destination. It marks the end of one development phase and the beginning of another that is far more demanding. The real question facing Bangladesh today is not whether it qualifies for graduation, but whether it is prepared for what comes after. Timing, preparedness, and reform priorities now matter more than celebratory headlines.

The issue of timing has returned to the centre of debate. November 2026 is fast approaching, and the global environment is far less forgiving than it was even a few years ago. Global demand is uncertain, geopolitics is tense, and trade is becoming increasingly conditional on compliance with labour, environmental, and governance standards. Graduation will imply that LDC-specific support measures, such as preferential market access and concessional finance, will be phased out. These cushions were never meant to last forever, but losing them prematurely, without adequate preparation, could expose fragile parts of the economy to sharp shocks. Graduation, by itself, does not generate growth. What matters is whether Bangladesh can function confidently in a world where LDC safeguards no longer apply.

This concern brings the Government’s Smooth Transition Strategy (STS) into focus. The STS, published in late 2024, was intended to serve as the country’s guide through the post-graduation period. On paper, it is comprehensive and well-intentioned. It recognises risks to trade, finance, and competitiveness. It acknowledges the dangers of excessive reliance on garments and the need to diversify the export base. It is the result of lengthy consultation, and it speaks the language of resilience, productivity, and sustainability.

However, a close reading of the document also reveals an awkward distance between ambition and execution. The Smooth Transition Strategy attempts to do too many things at the same time. It enumerates priorities without ordering them, actions without prioritising among them, and reforms without confronting the political and institutional barriers that have derailed similar initiatives in the past. Hard questions are acknowledged, then quietly sidestepped. Who will bear the costs of reform? Which entrenched interests will resist change? How will accountability be enforced when implementation falters? On these issues, the STS remains largely silent.

The deeper challenge is structural. Bangladesh’s graduation rests on impressive aggregate indicators, but beneath them lie persistent vulnerabilities. Income per capita has risen sharply relative to the LDC threshold, yet it remains far below the average for developing countries. Human development outcomes show progress, yet access to, and the quality of, health and education remain weak spots, while nutritional deficiencies continue to affect the majority of the population. Economic vulnerability indicators appear reassuring at first glance, but export concentration and climate exposure continue to pose serious risks. Graduation, in this sense, reflects how far Bangladesh has come, not how secure it has become.

Nowhere is this tension clearer than in trade. The export sector remains heavily concentrated in ready-made garments, which account for the overwhelming majority of export earnings and employ millions of workers. Preferential access to major markets has been central to this success. As graduation approaches, that access will gradually erode. In Europe, transition arrangements provide temporary relief, but elsewhere preferences will fade more quickly. Future access will depend not on status, but on compliance with demanding standards on labour rights, environmental protection, and sustainability. These are no longer optional extras; they are increasingly becoming the price of entry into global markets.

This shift changes the rules of the game. Competing on low wages and scale alone will no longer be enough. Firms will be judged on carbon footprints, supply-chain transparency, and worker welfare. For many exporters, especially smaller ones, meeting these requirements will be costly and complex. Export competitiveness could erode rather than strengthen in the face of global competition without focused assistance to raise standards, improve logistics efficiency, and build compliance capacity.

Financing conditions are also changing. Graduation will gradually narrow access to concessional finance, pushing Bangladesh towards costlier borrowing. At the same time, global lenders and investors are becoming more selective. They are scrutinising fiscal discipline, debt sustainability, and governance quality more closely. Here, domestic weaknesses become impossible to ignore. With a tax-to-GDP ratio that remains stubbornly low, fiscal space is limited. Public investment, social protection, and climate adaptation all compete for scarce resources. Without serious domestic resource mobilisation, development ambitions will increasingly outstrip available means.

Climate finance complicates matters even further. Bangladesh is unquestionably vulnerable to climate change, but access to climate funds is not automatic. It requires institutional readiness, credible project pipelines, and alignment with global best practices. Fragmented governance and weak coordination risk leaving resources untapped at a moment when adaptation and mitigation investments are becoming existential imperatives rather than discretionary policy choices.

Against this backdrop, the debate over whether Bangladesh should seek a deferral of graduation has gained momentum. The private sector has voiced concerns about preparedness, export competitiveness, and the pace of reform. Political uncertainty and macroeconomic stress have added to the unease. Supporters of deferral argue that a short delay could provide breathing space to stabilise the economy, complete key reforms, and strengthen institutions before fully stepping into a post-LDC world.

The case is understandable, but it is not straightforward. Deferral is neither automatic nor costless. Internationally, Bangladesh would need to demonstrate that extraordinary circumstances beyond its control justify postponement. Domestically, a request for more time risks being interpreted as hesitation or weakness. There is also a real danger that deferral could become an excuse for further delay rather than a catalyst for action. Time, by itself, does not produce reform. Political will does.

This is why the deferral debate can easily become a distraction. Whether graduation happens on schedule or after a brief delay, the underlying challenges remain the same. Export concentration, weak institutions, limited fiscal capacity, skill mismatches, and governance deficits do not disappear with procedural adjustments. If anything, graduation exposes them more starkly.

The private sector sits at the heart of this transition. Bangladesh’s growth story has been driven by domestic entrepreneurs, yet many firms remain trapped in low-productivity activities. Access to finance is constrained, especially for small and medium enterprises. Regulatory complexity raises costs and discourages investment. Technology adoption is uneven, and links between firms, research institutions, and training systems remain weak. Without deliberate efforts to upgrade productivity, diversify outputs, and build skills, the private sector will struggle to compete in a post-preference world.

Addressing these constraints requires more than policy statements. Reform in the financial sector will have to expand access to credit while restoring discipline and confidence. Industrial policy must move beyond protection and incentives towards genuine upgrading, innovation, and clustering. Skills development needs to respond to evolving technologies and labour market requirements, especially for women and young people. None of this is easy, but postponing it only raises the eventual cost.

At its core, the graduation challenge is a political economy challenge. Bangladesh has never lacked reform ideas. What it has needed are the appropriate incentives for those ideas to be translated into action. Rent-seeking networks, bureaucratic resistance, and short-term political calculations have repeatedly diluted reform efforts. Strategies are drafted, committees are formed, and reports are published, but execution stalls once vested interests feel threatened.

Breaking this cycle requires a different approach. Reforms must be prioritised and sequenced, not scattered across wish lists. Early wins that build credibility and public support matter. Mechanisms for accountability need to be strengthened if these commitments are to be translated into action. Reform coalitions must extend beyond the state, involving business, civil society, and the media to generate pressure for change. Above all, leadership matters. Without sustained political commitment, even the best-designed strategies will falter.

Seen in this light, graduation should be treated as leverage rather than a reward. It creates urgency. It narrows the room for complacency. It forces difficult conversations about competitiveness, governance, and inclusion. Used wisely, it can anchor reforms that might otherwise be postponed indefinitely.

The choice facing Bangladesh is therefore not a simple one between graduating now or later. The real choice is between drifting into an unprepared graduation or using that moment to redefine the country’s development trajectory. Deferral, if pursued, should be framed as a tool to accelerate reform, not to avoid it. Graduating on time, if chosen, needs to be supported by concrete actions that reassure citizens, investors, and partners alike.

Bangladesh has come a long way. That achievement deserves recognition. But the harder work lies ahead. Graduation does not end vulnerability; it reshapes it. The challenge now is to ensure that the next stage of growth is built on stronger institutions, wider capabilities, and a more sustainable model. Then graduation, rather than a ceremonial exit, will be remembered as the start of a more resilient future.

Selim Raihan Professor, Department of Economics, University of Dhaka, and Executive Director, South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM). He can be reached at selim.raihan@gmail.com

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.