Chittagong centred and de-centred A forgotten history

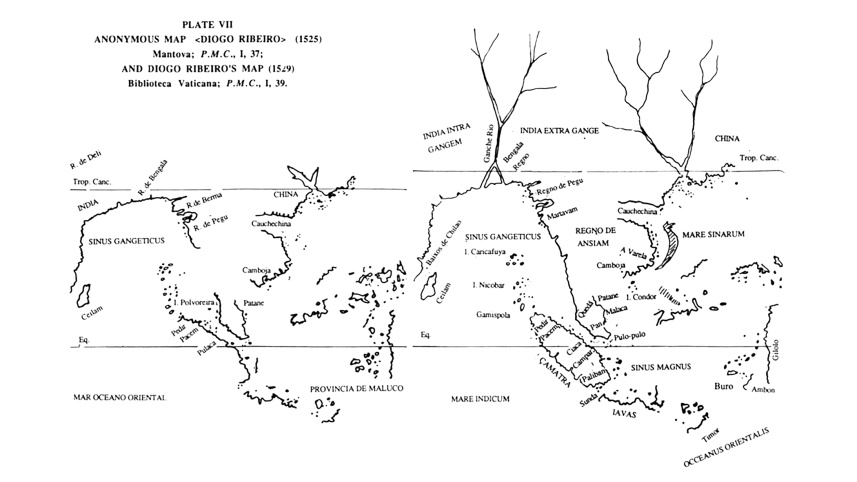

The previous article on Chittagong highlighted its nature as a frontier town in Harikela. The Markandeya Purana, one of the earliest of the major Puranas, validated Chittagong’s marginality from South Asia by locating it within Bhadrasva-varsha as opposed to Bharatavarsa. One of the island continents in Puranic cosmic classification, geographic imagination saw Bhadrasva-varsha as a separate region: “Hear from me of the continent Bhadrāśva, which is situated east of the magnificent eastern mountain Devakūta.” At the same time, given Chittagong’s thousand-year-plus history in trade, its absence in sea-faring texts such as Periplus Maris Erythraei and in early navigational accounts is strange, unless we reference the geographer Claudius Ptolemy’s placement of Chittagong within India Extra Gangem as opposed to India Intra Gangem, or “India within the Ganges,” within which lay India.

The Cantino Planisphere of 1502, which heralded Portuguese arrival into the Bay of Bengal, marked Chittagong as a major portal. However, this would be disputed shortly thereafter; the Jorge Reinel map of 1510 highlighted only Hormuz, Cambay and Melaka, and depicted, in addition, Goa, Dabhol, the Malabar ports and Sri Lanka. Chittagong was not depicted. Chittagong would evolve thereafter from a point within a string of ports to a sub-region among a band of coastal states, and finally, to a princely territory in the traveller’s imagination.

I. A Janus-faced history

One reason for Chittagong’s absence from historical records is that for a large part of its life it was under Arakan. Therefore, rather than studying Chittagong from Indian sources, reconstructing its history from Arakanese records that have engaged scholarly attention since the late nineteenth century makes more sense.

Arakan Chandra king Dhrtichandra’s downfall (ca. 665) encouraged Chittagong’s elite to declare independence from Arakan with silver coins carrying the legend Harikela above the bull. These are among the most plentiful coin issues of Southeast Bengal. Of similar style and identical weight standard to the later Chandra coins from Arakan, their iconography suggests Saivite and Vishnuite affiliation, but instead of giving the name of a ruler on the coins, as was done in Arakan, a place-name or polity is given. It is unusual for coins of this period to inscribe Harikela rather than the king’s name, but as maritime trade had become important in the region, probably merchant families or guilds wielded power, with any ruler there taking a purely ritual role and not being involved in coin issuance.

The Burma-based Pyu Sriksetra–enclosed “urban” community of ca. 638, and the rise of the Sumatra-based Srivijaya realm in the Indian Ocean maritime network sometime prior to 681, helped Chittagong. Trade with them offset the hostile conditions created by the Nan Zhao polity (729) in Yunnan, which saw the overland route—previously transmitting Vajrayana interactions from Bengal—becoming increasingly unstable. A third factor, noted by the late numismatist Nicholas Rhodes, was a cluster of events adversely affecting Samatata’s networks—the end of Amshuvarma’s rule in Nepal (621), the near-simultaneous deaths of Tibet’s Songtsen Gampo, Kamrup’s Bhaskaravarma and North India’s Harshavardhana (all ca. 650), and the Sassanid fall in Persia (651). The trading hub now shifted southeast from Samatata. Marundanatha’s seventh-century Kalapur copperplate had included Srihatta in coastal Samatata, but large deposits of Harikela coins indicate it becoming part of eighth–ninth-century Harikela. Clearly, Samatata’s declining trade had shifted Srihatta’s networks towards Harikela.

II. An early centring in Harikela

Seventh-century Chittagong city started rewriting the cultural paradigm from the margin, challenging traditional models of linear and totalisable historiography. Such marginocentric cities are at odds with the mainstream culture within which they find themselves. Francois Pyrard wrote of the wars between Arakan, Ayutthaya and Pegu: “the Gentile people of this Bengal country (!) have for their pagoda, or idol, a white elephant; it is but rarely met with, and is deemed sacred. The kings worship it, and even go to war to get it from their neighbours, not having one themselves, and sometimes grand battles are fought on this score.” This clearly references an Arakanese and not Bengali practice; white elephants were frequently seen in Chittagong when it was under the former’s rule. But marginocentric cities also find their own agency, as seen in Arakan’s sixteenth-century trilingual coin issues from Chittagong.

Buddhist king Devātideva’s land grant of 715 referenced Harikelayam (Harikela’s people)—the first epigraphic reference to Harikela to date. A Harikela kingdom emerged soon after, embracing the area north of Samatata from Chittagong to Comilla, forming a mandala with the capital (vāsaka) at Vardhamānapura (present Bara-Uthan village in Patiya Upazila). Amity with Arakan’s Vesali (Waithali) dynasty is seen in matrimonial ties, genealogical connections, shared use of specific script types, peculiarities in documentation of endowments to religious institutions, common Bengali-Hindu style regnal names, and overlapping coinage traditions. Arakan Chandra ruler Sri Dharmavijaya’s coins of ca. 750 are found not only in the Akyab area, but also in Chittagong, southern Tripura, and in and around Comilla. It seems that he reasserted hold over Chittagong and over all of the now-declining kingdom of Samatata. After his death, Arakan’s influence may not have extended north of Chittagong, as no coins of the later Arakan kings have been found there.

As an entrepôt of Bahr Harkand, Harikela participated in what Australian historian Geoff Wade has called the ‘ninth-century age of commerce’. Slightly after the mid-ninth century, a huge cache of coinage with the legend ‘Harikela’ was issued in the Samatata area as well. Despite its marginal location on major transoceanic routes, Chittagong became a gateway for Arab merchants. Sulaiman states, ca. 851, that at Samandar (? Chittagong) valuable muslin was exported. Trade was carried out using cowrie shells, which were the current money of the country, although Bengal possessed gold and silver.

By the tenth century, however, Harikela was monetised. Fewer land grants compared to Samatata, and the purchase of land for donation, indicate a scarcity of free land (hill tracts and saline lands impeded cultivation). Suchandra Ghosh has pointed out that lands were purchased with coin money and granted to the donee, while no such reference to direct purchases can be found in the Samatata grants.

Harikela re-enters the early tenth-century historical record, again as a mandala with Vardhamānapura as capital under Rājādhirāja Samaramargānka Attākaradeva. Perhaps hailing from Arakan, was he Bengal’s Trailokya Chandra’s (ca. 905–25) vassal? An Ākara-type coin has been found with the name ‘Attākara’, suggesting links between the Ākara families of Chittagong and Arakan. Sri Simghagandachandra’s late tenth–early eleventh-century coin in Arakan’s Kywede hoard has a script similar to the proto-Bengali script. An eleventh-century Shitthaung Pillar inscription evinces contacts with Southeast Bengal’s Govindachandra (r. 1020–55).

III. Interregnum

The period from the ninth–tenth centuries (when Arab traders came to Samandar) until the thirteenth (when Hinduism and Burmese Buddhism entered Chittagong and Arakan) is hazy for Chittagong, but records suggest that a tentative centring had lapsed into a de-centred space. Did the de-centring have something to do with events in Arakan in the post-Vesali period, which saw a break with earlier traditions and the abandonment of symbols of pre-tenth-century rulership? If so, our argument for seeing Chittagong’s history through an Arakanese lens is reinforced.

The eleventh century saw the Bengal–Arakan compact collapsing. The Vesali kings had adopted Bengali-Hindu style regnal names, but in the interregnum between the Vesali and Laun-kret (Launggyet) dynasties, and even into the early Laun-kret period, regnal names were either of local origin, or of a high-status Bagan-Buddhist model, or drawn from post-Bagan era Burman dynastic lists. Names began fitting more closely into the pattern of Burman kingship. Although Bagan’s hold over Arakan was purely nominal, inscriptions were no longer written in Devanagari but in a Bagan-style Burmese script instead. As proof of the breakdown of the Vesali kingship model, there were no further issuances of coronation coins. This corresponds to a similar lack of minted coinage in eleventh- to thirteenth-century Bengal.

IV. De-centring

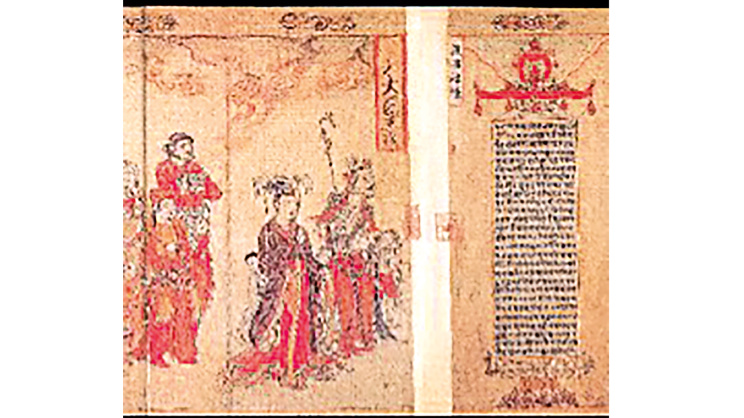

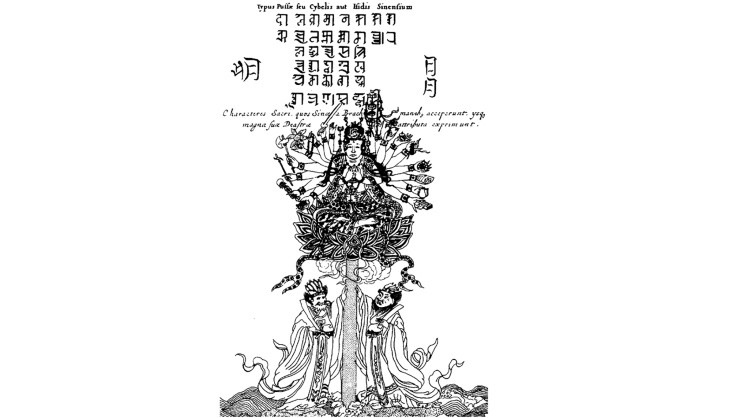

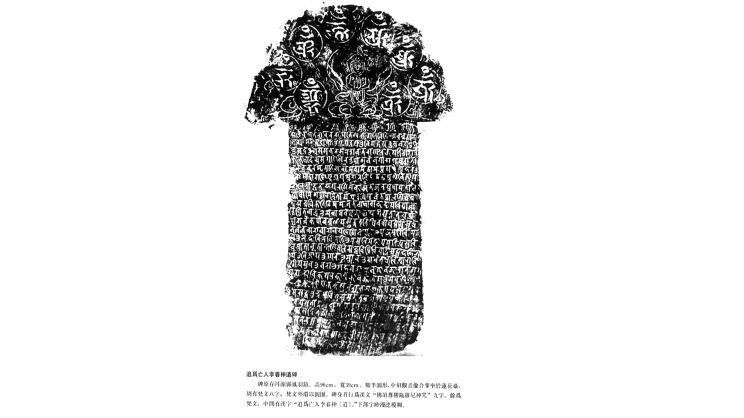

Chittagong was now constrained at either end. Rajendra Chola I invaded Bengal ca. 1023. Bagan’s Anawrahta invaded Arakan ca. 1018, and his successors claimed the northern part of Arakan’s Chandra kingdom. Tributary relations with Bagan gave Arakan a direct route into Yunnan. Zhou Qufei stated (1178) that Dali was only five days’ journey from Bagan. Did Chittagong leverage this new connection? A pictorial description of a mission through eastern India to the Dali court circa 1180 shows Vajrayana (Tantric) Buddhist symbols. A Yunnan stamp with Nagari-style characters and an image of Pussa, the Chinese Cybele or Isis, along with ‘the Sacred Characters which they borrowed from the Brachmans, and which express the great attributes of the deity’ in a work dated 1667, shows further Indic influences (images 1–3). Were these influences transmitted through Chittagong?

Coins and inscriptions reveal Harikela to be a land without a centre, unlike Pala Bengal, Laun-kret Arakan, and Burmese Bagan at this time. The restricted circulation of the Ākara coins, despite Arab traders visiting the port of Samandar from the first half of the ninth century, suggests they may have been withdrawn from circulation and melted due to the demands of foreign trade. But al-Idrisi’s description, ca. mid-twelfth century, suggests an extensive hinterland rather than declining numismatic vitality—he found aloes wood, yak tails, rhinoceros horns, and forest products from Kamarun (Kamrup) being exported from Samandar.

The Harikela coins circulated for nearly three centuries after the Samatata coins vanished. Then, a political and economic destabilisation across mainland Southeast Asia saw a simultaneous disappearance of minted coins at Sukhothai, Bagan, Angkor, and Harikela. Standardised silver and gold lumps served for transactions. Land grant records, not coins, reveal Harikela’s subsequent history. Since Arakan’s kings were devout Buddhists (Dharmavijaya [ca. 665–701] had called himself parameśvara, playing on a term referencing Siva, ‘who has given cause for crying throughout the Rudra-lineage’ [i.e. Siva] in Vesali’s Odein inscription), what happened when Nathism operated as a bridge between Tantric Buddhism and Saivism, or when land grants invoking Hindu deities were made? The distinguished historian-archaeologist Ahmad Hasan Dani noted that Ladahachandra (1000–20), although Buddhist, was a Krishna devotee. Land was granted to the deity Ladaha-madhava-bhattaraka at Pattikera, and he performed tarpana for his father, the deceased Kalyanachandra, at Varanasi.

Ranavankamalla Harikeladeva’s Mainamati copper-plate (1220) shows Harikelamandala coming under Comilla’s Pattikera kingdom in Samatata, on the Meghna’s eastern side between Dhaka and Chittagong. Amicable contacts with Tripura and Arakan are visible in terracotta plaques representing Arakanese and seemingly Burmese peoples at Mainamati. Sena chieftain Damodara Deva (1231–43), profiting from turmoil after Visvarupasena’s death, then established an independent kingdom comprising Tripura, Noakhali and Chittagong. Archaeologist Rajat Sanyal sees a syncretic milieu appearing with land grants to Brahmans (Damodara’s Chittagong Plate of 1243), Buddhist viharas (Pandita Vihara was a centre diffusing Mahayana Tantricism), and images (Chittagong was also a Mahayanist site with a large number of images; two were bronzes of Padmapani Avalokitesvara). A bronze Buddha image found in a mosque depicts him with his left palm placed below the navel and a vajra at the pedestal’s centre. Another bronze Buddha image, similar in all respects to the former, is covered with gold leaf. In 1927, a large Mahayanist hoard was discovered at Anwara: 61 Buddhist images, two miniature shrines, and three image fragments. Some show affinities to Nalanda bronze images, and others to Burmese bronzes, proving the existence of a local centre of beautifully executed Buddhist art that formed a link in the chain of its development and extension to Burma, Lan Na, Sukhothai and Sri Lanka.

V. Breakdown

The thirteenth century was very turbulent for the Bay polities. Mongol expansion left polities without discernible centres in the region. The southern Bay of Bengal vacuum created by the thirteenth-century Chola decline was exacerbated by Srivijaya’s fading networks. Ligor (Nakhon Si Thammarat), Boni (northwest-coast Borneo) and Jambi (mid-east coast Sumatra) contested its intermediary role between India, China and Southeast Asia. Majapahit Java and Sukhothai became commercially prominent. Gulf of Siam polities traded directly with Yuan China, which also accessed goods through the Pandya Coromandel port of Kaveripattinam, vital to China as a maritime pathway to the Malabar coast and, thence, to West Asia.

Bengal was seemingly bypassed. Zhao Rugua’s description of Bengal in ca. 1225 says:

‘Pong-k’ie-lo of the West has a capital called Ch’a-na-ki (? Pandua). The city walls are 120 li in circuit. The common people are combative and devoted solely to robbery. They use (pieces of) white conch shells ground into shape as money. The native products include fine swords, tou-lo cotton stuffs and common cotton cloth. Some say that the law of the Buddha originated in this country…’

But Wang Dayuan (ca. 1311–?) says Pengjiala (Bengal) remained an important destination for Chinese traders as a gateway to Delhi and Tibet. Ma Huan’s The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores said in 1433:

‘Travelling by sea from the country of Su-men-ta-la (Sumatra) … the (Nicobars) are sighted, (whence) going north-westward for 20 li one arrives at Chih-ti-chiang [Chittagong]. (Here) one changes to a small boat, and after going 500 odd li, one comes to So-na-erh-chiang [Sonargaon], whence one reaches the capital.’

Around 1436, Fei Xin’s The Overall Survey of the Star Raft said:

‘This country has a sea-port on a bay called Ch’a-ti-chiang; here certain duties are collected … After going 16 stages (we) reached So-na-erh-chiang, which is a walled place with tanks, streets, bazaars, and which carries on a business in all kinds of goods… Going thence 20 stages (we) came to Pan-tu-wa [Pandua], which is the place of residence of the ruler.’

The upper Bay trade had become important again. The decline of land-based trade routes forced Arakan’s kings to regard maritime trade as their new primary link to the outside world. Maritime trade provided new economic opportunities for kingly legitimation. Fifteenth-century Mrauk U kings abandoned the Burmese kingship model and adopted the Bengal Sultanate’s coinage styles and regnal names. Min Saw Mon used the name of Suleiman Shah (1430–34); Min Khayi was Ali Shah I (1434–59); Basawpyu was Kalima Shah (1459–82); Min Dawlya was Maw Ku Shah (1482–92); Basawnyo was Muhammad Shah (1492–94); Ranaung was Nuri Shah (1494); Salingatha was Sheikh Abdullah Shah (1494–1501); Min Raza was Ilyas Shah (1501–13); Min Saw O was Zala Shah (1515); Thazata was Ali Shah II (1515–21); Kasabadi was Jali Shah (1523–25); Min Bin was Zabauk Shah (1531–53); Min Phalaung was Sikandar Shah I (1571–93); Min Raza Gyi was Salim Shah (1593–1612); Min Khamaung was Hussain Shah (1612–22). With the Bay now open to growing royal interest in maritime trade, these rulers embraced the shift, changing from petty monarchs satisfied with political isolation to kings bent on empire and new economic opportunities. Chittagong would feel these effects. At the same time, it would become enmeshed within global trading networks—and that will be the story my next article will recount.

Rila Mukherjee is a historian and the author of India in the Indian Ocean World: From the Earliest Times to 1800 (Springer Nature, 2022) and Europe in the World from 1350 to 1650 (Springer Nature, 2025).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments