Chittagong, before Chittagong: An early history

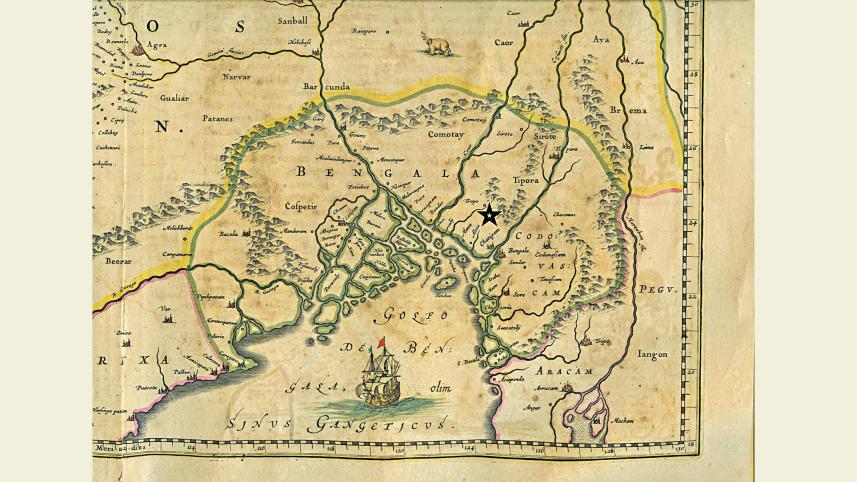

In the remote east of a region once called Harikela lies Chittagong, an upper Bay of Bengal port city at the juncture of the medieval Bengal, Arakan and Tripura kingdoms. Once central to Portuguese and French expansion, it later became marginal to British rule. Independence in 1947 and liberation in 1971 then imposed state and district boundaries bearing little relation to Chittagong's once expansive surroundings. The US-led post–Second World War Area Studies programme conducted the final surgery by bifurcating the region between South and mainland Southeast Asia.

In historical writings, Chittagong is both a place name and a sub-region within the larger geographic-cultural unit of Harikela. The place name 'Chittagong' refers to both the port and the city. But since decisions about geographic framework or regionalisation are rarely as explicit as those involving chronological framework, or periodisation, the contours of the Chittagong sub-region remain unclear. It includes the area lying east of the Karnaphuli River. This area neighbours Arakan, with which Chittagong has had a long association.

I. Unstable land

Dating from the seventh century and conflated with Yavadvipa by travellers, Chittagong was an autonomous border town and port town on a dynamic but unregulated water frontier. Located at the apex of the Bay of Bengal and straddling the fault line between South and Southeast Asia, it was subject to forces of earth, wind, and water. Its site is distinctive, with a complex land–river–sea ecosystem marked by unstable sea islands (char) at a short distance from the mainland, separated by shallow waters and mangroves. To its south, where Arakan and Bengal overlap, the Arakan Yoma barrier forces riverine or coastal voyaging along a coast interrupted by channels owing their waters to tidal actions. To its north-west, waterbodies (haor in the local dialect, from the Sanskrit sagar [sagaranupa], or sea) supplement the Meghna–Brahmaputra waterway as the 'Eastern Sea'. In this water frontier, many looked to the sea and to maritime trade, smuggling, raiding, or even piracy for survival.

My late mother, who came from the adjacent Noakhali district, spoke nostalgically of the floating markets and waterborne passageways she saw as a child. Instead of bullock carts, people travelled by boat, for this was a marine land.

The waterbodies underwent continuous evolution. As they expanded, lands were submerged; as they receded, new lands sprang up. Although what happened earlier is unknown, we have some records from the sixteenth century onwards. The Ottoman navigational treatise Muhit (1554) speaks of extensive level alterations and alludes to navigational dangers among islands that have since disappeared. Maheshkhali Island, separated from Chittagong by the Maheshkhali Channel, originated from a severe cyclone and tidal bore (1559). The merchant Cesare Federici (August 1569), the traveller Ralph Fitch (March 1588), and the adventurer Glanius (October 1661) all mentioned severe cyclones in the region.

Seismic disturbances also rocked this coast. An earthquake in 1678 affected Arakan; the one of April 2, 1762 saw the submergence of 60 square miles near Chittagong. A tsunami elevated Arakan's coast by some three to six metres, raising Foul Island by nine feet and Cheduba Island's north-west coast by 22 feet above sea level.

Seismic disturbances also rocked this coast. An earthquake in 1678 affected Arakan; the one of April 2, 1762 saw the submergence of 60 square miles near Chittagong. A tsunami elevated Arakan's coast by some three to six metres, raising Foul Island by nine feet and Cheduba Island's north-west coast by 22 feet above sea level.

II. Marginocentric space

Straddling Indic, Buddhist, and Islamic realms—neither wholly South Asian nor entirely Southeast Asian in nature—the political borders of both city and sub-region were always weak compared with the strength of their economic and cultural relations. Yet because border social dynamics can affect the formation and territorialisation of states, marginocentric cities like Chittagong have sometimes exerted profound influence on continental histories.

'Marginocentrism' is a term coined by Marcel Cornis-Pope in 2006 to explain the evolution of cities in East-Central Europe. These cities, by driving historical change, can challenge mainstream paradigms. But unlike Fernand Braudel's primate cities, they lead a solitary existence. While Braudel's cities assume a role in the market economy by virtue of their relationship with the surrounding rural area, a patchwork of urban–rural interactions forms the basis of the marginocentric city's market-economy exchanges.

III. Early market economy

When the decline of the Later Chandra dynasty in Arakan in c. 957 presented an opportunity for Chittagong to declare autonomy from Arakan, it could connect rural industrial production with trading networks in the upper Bay's regional economies as an entrepôt, becoming a coordination and communication centre for long-distance bulk trade supplying non-agricultural populations.

As a port, it simultaneously assumed importance in a growing commercial economy as a relay point within regional trading networks, including bulk shipping and the trade in staples such as rice, salt, and cottons, as well as the aloes and eunuch trades. David Ludden has noted that Chittagong port historically operated as a hinge between two commodity circuits: the Indian Ocean circuit and the upstream/downstream, river-borne Brahmaputra–Himalaya–Tibet–Yunnan circuit. This second circuit also linked it to Persia via Magadha, through a region to its north-west called Pundravardhana. A third circuit carried cowries across the seas from the Maldives, through Bengal's rivers and across the tropical mountains of Yunnan and Burma, connecting Chittagong's agrarian frontier with India, China, the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and larger oceanic networks.

A degree of control over provisioning is evident in Chittagong's progressively large trade portfolio, which reveals its expanding reach: gold, silver, rubies, cowries, iron, steel, tin, timber, pepper, spices, salt, sugarcane, cottons, muslin, linen, silk, indigo, rice, corn, a wide range of fresh and dried foods, preserves, butter and other dairy products, cattle, horses, elephants, rhinoceroses, turtles, leopards, tigers, red lacquer, wax, and manufactures such as boats, chinaware, crockery, cookware, and cane and rattan furniture (as good as those of China, according to the seventeenth-century traveller François Pyrard). Was this provisioning undertaken by outsiders or by a local mercantile class? Exports and re-exports suggest trade with the Maldives, Persia, Africa, and China, the last particularly in exotic animals and rare animal products. Chittagong's rice and slave exports were crucial to Dutch Batavia.

IV. Chittagong Port: Hazy history, few sources

Chittagong's early history is unclear. Despite its strategic location when compared to Samataṭa, Harikela emerges late in the historical record. It was seen as an extension of King Sanjaya's Hinduised Java, since seas did not constitute natural frontiers as they do now, and the notion of borders was then fluid. Rachel Midura points out that events and perceptions generated a spatial 'othering' through the influence of factors other than geographic proximity; journeys by sea or through mountain passes could appear as a single route in a traveller's narrative, and instead of emphasising sovereign states, as cartography does, itineraries linked distant places through commercial and cultural pathways.

The names Jambudvipa and Yavadvipa were used interchangeably for Java and Chittagong. In c. 413, returning to Guangzhou from Bengal, the Chinese Buddhist cleric Fa Xian stopped at an unspecified port in Yavadvipa which practised a blend of Brahmanism and animism. He noted that 'heretic Brahmans flourish there, and the Buddha-dharma hardly deserves mentioning'. Was this perhaps Chittagong?

Records indicate that Samataṭa had links with the Buddhist polity of Srivijaya and perhaps with China as well. Sources reference pilgrim circulation and the collection of Indic religious texts there; it was a rich region marked by a gold coinage and a flourishing commerce. Yet, as historian Suchandra Ghosh reminds us, while Chittagong supposedly adopted Buddhism late compared to Samataṭa, when Xuanzang mentioned, c. 635, Samataṭa's relations with Southeast Asian polities, these must have occurred through Harikela, as Samataṭa had only the fluvial port of Devaparvata. Even so, early notices, including Xuanzang's, ignore ports in the region. It was only c. 675 that Yijing saw this easternmost region emerging as a political frontier (the early Harikela coins appeared c. 665). His contemporary Wu Hing disembarked at an unnamed port here; possibly this was Chittagong, which had appeared as both place and port by then.

V. Chittagong city: Late emergence

Early Chittagong's nature is therefore enigmatic. Slow to appear as a port, it was even slower to rise as an urban centre. Some third-century Kushana gold coins are found at Chandraketugarh in western Bengal, but none at all at Chittagong, which clearly did not play a major role at that time. Early Arakan yields a greater number of sources for studying late medieval Harikela, but it provides no numismatic evidence to suggest that Chittagong port was operational in the early sixth century, or that it was in the hands of Arakan's Buddhist Chandra kings.

Late sixth-century Gupta-style gold coins are found in Comilla, southern Tripura, and Noakhali district, but not at Chittagong. Subsequently, despite the influence of the port-town-based Vesali-Chandras (c. 788–957) in the Chittagong–Tripura area, the fact that Vesali-Chandra coin distribution is limited to the Danra-waddy river basin (the central Arakan littoral) suggests that Vesali's effective political control was not widespread.

Chittagong would later become central in shaping the course of the region's history, but in the absence of adequate records, how do we assess the relevance of local occurrences—such as state formation, Hindu–Buddhist clashes, and conflicts between Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist merchants for control over Chittagong—for the unfolding of regional processes, including the growth of the Arakan and Bengal polities, or the mismatch of Muslim and Buddhist forces in the upper Bay? Or, possibly, was there an even wider conflict between Buddhists, Muslims, and Christians for control of sixteenth-century Indian Ocean trade? At this time, Arakan, with its Mrauk U centre and trade outlet at Chittagong, occupied a median position between the medieval agrarian states of the interior and the coastal trading polities. This is also the period when sources on Chittagong become more plentiful. There is thus an asymmetry in our perception of time and space in this borderland spanning South and Southeast Asia.

VI. A borderland without elites

Although network centrality made it a significant place, Chittagong's frontier location under multiple hegemonies produced a historiographic erasure. Its historical development was determined simultaneously by politics in Bengal and Arakan, and by the social, economic, and political interactions between them.

It has been said that a region's representation and public image are products of status and power, yet Chittagong's urban hierarchy or its elite-dominated order lacks definition. David Ludden noted that early Chittagong was not marked by an ethnically distinct population that could evolve into an elite class. This makes Chittagong's recorded history strangely timeless, as elites produce historical records and typically live in central territorial sites with networks of coercion and patronage.

Chittagong's elite reach over resources was sporadic, suggesting limited integration into neighbouring power networks. If the state, regional elites, and the local population are knit into a coherent power structure with relatively low tension, the borderland is likely to be peaceful and flourishing. This was not always the case for Chittagong. Rudimentary elite classes emerged after the Chandra decline in 665, and again around 957, and yet again following Gaur's decline after 1538, but further progress was thwarted each time. Despite these setbacks, Chittagong's elites were sufficiently integrated into networks of state power to issue their own coinage to conduct trade during periods of their existence, and to work generally in alliance with political authorities to control the region.

VII. A visible heterogeneity

We cannot fully envisage Chittagong's social world, but its names in various languages and diverse dialects reveal its heterogeneity. In the local dialect it is Cat'ga or Catiga. The Anglicised 'Chittagong' derives from the eighteenth century. The Sanskrit Chattagrama (literally 'four villages') is similar to the Buddhist Chaityagram (chaitya meaning pagoda). It is also the ninth-century Arab Samandar, famous for the aloeswood coveted in Persia and China. Other names include the seventeenth-century Mughal 'Islamabad'; the sixteenth-century 'Porto Grando'; the fifteenth-century Bengala–Banghella; the fourteenth-century Sadkawan–Sutirkawan of Ibn Battuta; and the Bengali Roshang (also used for Arakan's capital Mrauk U and Bengal's mint town Fathabad).

In Puranic and Tantric texts, it appears as Harikela and Cattala. In tenth-century Tibetan and Arab texts it is Jwalandhara and Karnabul (Karnaphuli). Other variants include Tsi-Tsi-Gong, Che-ti-chiang, Shetgang, Xatigam, Chatgaon, and Chartican. Of particular note are the Arakanese Caittegarm—meaning 'chief' or 'superior fort'—and Cit-taut-gaurm, meaning 'do not make war'.

Badr Pir is Chittagong's patron saint and guardian of rivers. His influence is visible in place names such as Badartila (Hathazari thana), Badarkhali (Chakoria thana), Badarkua (Cox's Bazar), and the ninth–tenth-century Badr Maqam shrines—situated on boulders and crags at river mouths to mark a maritime circuit—worshipped by Hindus, Muslims, Chinese sailors, and local fishermen at Akyab, Cheduba, Thandwe (Arakan), and Mergui (lower Burma).

Chittagong port historically operated as a hinge between two commodity circuits: the Indian Ocean circuit and the upstream/downstream, river-borne Brahmaputra–Himalaya–Tibet–Yunnan circuit. This second circuit also linked it to Persia via Magadha, through a region to its north-west called Pundravardhana. A third circuit carried cowries across the seas from the Maldives, through Bengal's rivers and across the tropical mountains of Yunnan and Burma, connecting Chittagong's agrarian frontier with India, China, the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and larger oceanic networks.

VIII. Question

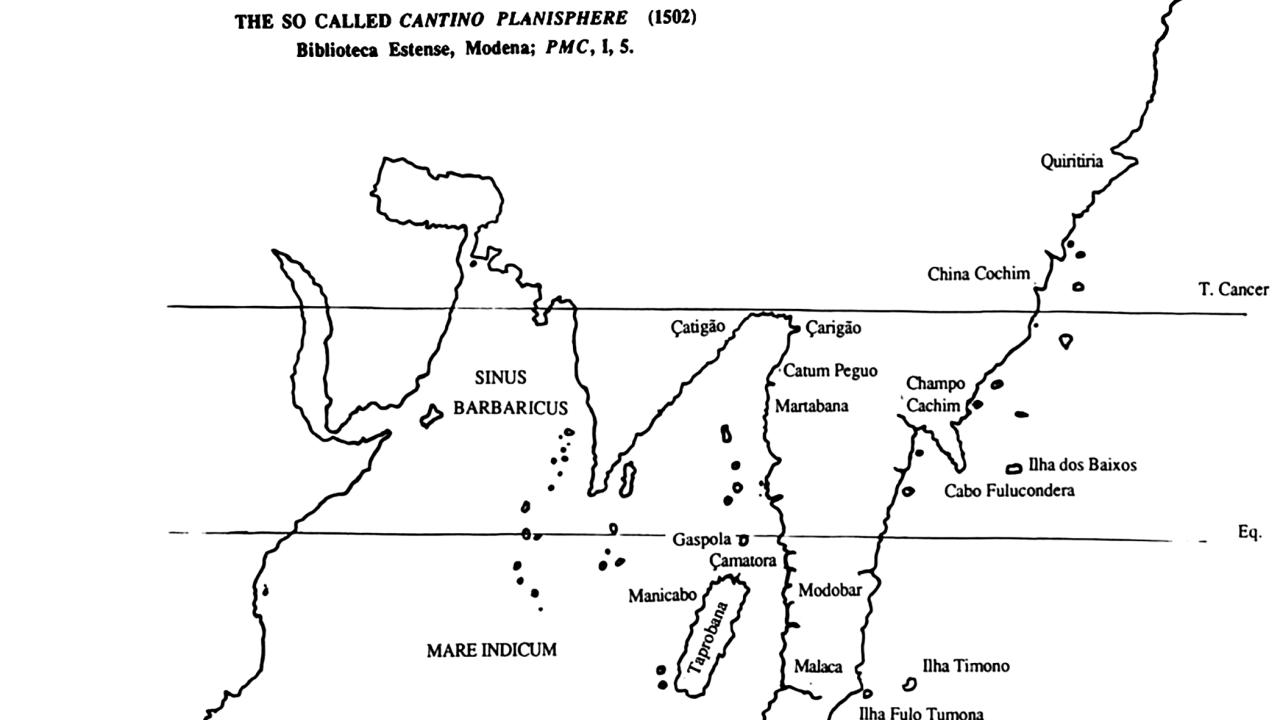

How, then, did this marginal land transform into the Cantino Planisphere's major portal in 1502? The Portuguese diarist Tomé Pires (1515) observed a westward commercial networking from Chittagong, with Persian, Rumi, Turk, and Arab merchants present there, as well as traders from Chaul, Dabhol, and Goa, while the Portuguese epic poet Camões (1572) emphasised eastern networks:

'The City CATHIGAN would not be wav'd,

The fairest of BENGALA: who can tell

The plenty of this Province? but its post

(Thou seest) is Eastern turning the South-Coast.'

Rila Mukherjee is a historian and the author of India in the Indian Ocean World: From the Earliest Times to 1800 (Springer Nature, 2022) and Europe in the World from 1350 to 1650 (Springer Nature, 2025).

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.