Amar Ekushey: Before Bangla became a demand

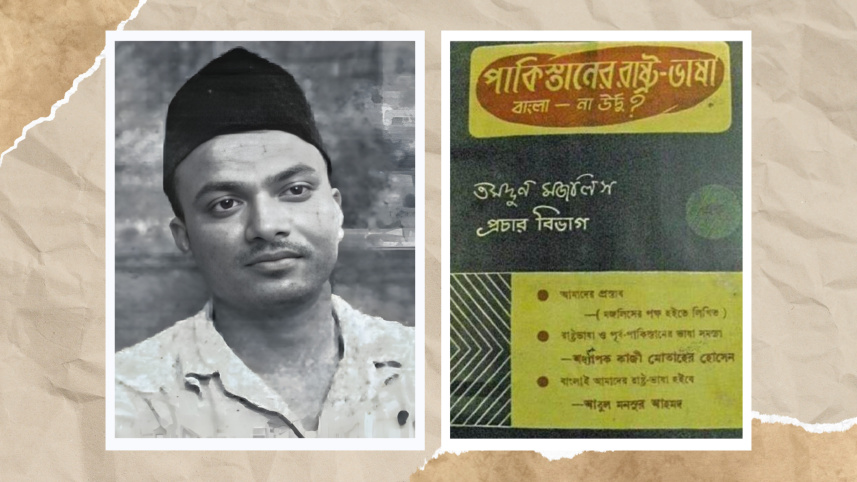

Principal Abul Kashem is an unforgettable figure in the history of the Language Movement. On September 1, 1947, under his leadership, Tamaddun Majlish, the initiating organisation of the Language Movement, was established.

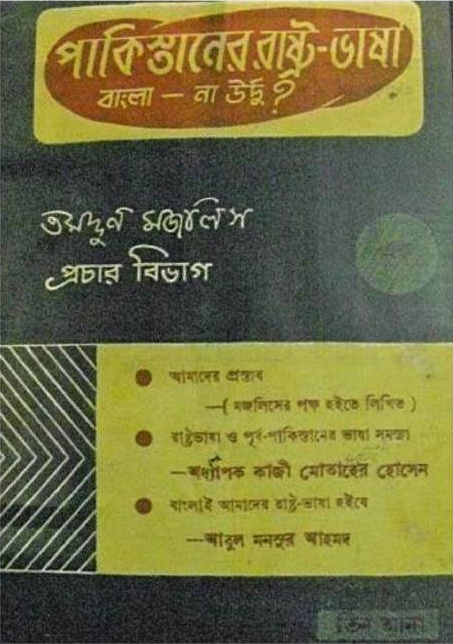

On September 15, 1947, he published Rashtro Bhasha Bangla Na Urdu?, the first booklet containing the demand for Bangla as a state language. He was also the founder of the Language Movement’s mouthpiece, Weekly Sainik.

Here, we publish translated excerpts from an interview with this historical figure. The interview was published in Bhasha Andolon Shatchallish Thake Baana (1993), compiled by Mostafa Kamal.

How was the Language Movement initiated?

The Language Movement was initiated through the Tamaddun Majlish (TM). On September 1, 1947, it was established at 19, Azimpur. I was a professor in the Physics Department and used to live at 19, Azimpur. I used to think deeply about Bangla as a state language and as a medium of instruction. I shared my ideas with my friends. Syed Nazrul Islam and Shamsul Alam were directly involved in the establishment of TM.

What were the primary actions that TM took to create awareness about Bangla as the state language?

Organising literary meetings and seminars in different places, including the university campus, was among the many primary initiatives of TM. These meetings used to take place on the lawn, which back then was adjacent to the south-west of the University of Dhaka, and at the Muslim Hall auditorium. Moreover, to create public opinion, we used to publish statements and handbills. The first book that demanded Bangla as the state language, Pakistaner Rashtrobhasha Bangla Na Urdu?, was published by me as its editor. The main point of the book was that the language which ensures that the strength of the nation is not wasted, and the language which its citizens can easily learn, speak, and write, should be the state language of the country.

What kind of attention did Rashtro Bhasha Bangla Na Urdu? receive from university students?

To be honest, we did not find even five people on the campus willing to buy this book. The attainment of Pakistan had captivated the whole nation. At that time, everyone used to try to make us understand how “dangerous” it would be to raise the issue of more than one state language, and how “unrealistic” a proposal it would be for Pakistan, in particular, to have two state languages.

Did you carry out any activities outside the campus back then?

Yes. We discussed this issue with certain government officials and litterateurs, and achieved some success there. At that time, we collected the signatures of several eminent personalities of the country and prepared a memorandum. The memorandum was presented to the government and published in some newspapers. The local newspapers of that time did not give this issue much importance. Ittehad, based in Kolkata and edited by Abul Mansur Ahmad, and Weekly Insaf, gave tremendous support to this cause.

How did Sainik start its historic journey?

Sainik, a weekly publication, was first published on November 14, 1948. A few sincere employees helped me to publish this revolutionary newspaper as the mouthpiece of TM. It played a historic role in the Language Movement.

When was the Rashtrabhasha Sangram Parishad formed? Why did you feel the necessity to establish such a platform?

After the meeting at Fazlul Haq Hall [October 1947], we, the members of TM, decided to form the Rashtrabhasha Sangram Parishad. There were various discriminatory practices against Bangla, such as the use of only Urdu and English on postcards, money order forms, rail tickets, and currency, as well as the omission of Bangla from the syllabus of the Pakistan Central Public Service Commission.

The Education Minister, Fazlur Rahman, even pleaded that Urdu should be the only state language. Unfortunately, students, teachers, and the intellectual community were quite lenient about the degrading status of their mother tongue. We feared that the government would try to impose Urdu as the sole state language by exploiting this state of leniency. So we took the initiative to mobilise people against this one-sided decision.

How did the Parishad start working?

We went to meet the Education Minister, Fazlur Rahman, at Nazira Bazar. We had a heated debate over the question of Bangla as a state language. He treated us badly, and that infuriated us. We took the initiative to present a memorandum demanding Bangla as a state language. We collected thousands of signatures in favour of this demand and submitted the memorandum to the East Pakistan government. We appealed to the government to immediately declare Bangla as the state language and the medium of instruction in East Pakistan.

Can you remember the statement issued against the decision of the Pakistan Central Public Service Commission to omit Bangla from the syllabus of the Civil Service Examination?

In November 1947, the Secretary of the Pakistan Central Public Service Commission issued a circular to the public universities outlining the syllabus of the civil service examination. There were 31 courses, of which nine were on languages such as Urdu, Hindi, English, German, French, and even dead languages like Latin and Sanskrit. But Bangla, the language of the majority of Pakistan, was omitted from the syllabus. This was proof of sheer disregard and negligence towards the Bangla language. I sent a statement of protest to Ittehad, severely criticising this malicious intent of the government. It was published around the end of December, along with an editorial by Abul Mansur Ahmed, who also vehemently opposed the government’s decision. Later, the concerned ministry expressed regret, describing it as an inadvertent mistake. This casual response infuriated us even more.

Did the Rashtrabhasha Sangram Parishad take a lead role in launching the programmes of March 11, 1948, demanding Bangla as the state language?

Yes, a meeting was held by the Sangram Parishad on March 7 at Fazlul Haque Hall, where it was decided that a strike would be observed on March 11 in Dhaka and across the state. The programme was highly successful. The police charged the crowd with batons and tear gas. Many students were injured, and many others were arrested. As a result of the movement of March 11, the demand for Bangla as the state language gained new momentum.

[The interview has been translated by Samia Huda]

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.