Between memory and truth: Mark Tully and the Bangladesh he witnessed

I first met Mark Tully a decade ago, on an ordinary London evening. The DSC Prize for South Asian Literature shortlist event at the London School of Economics (LSE) had just ended. In the Old Building, voices drifted in soft murmurs, thoughts remained half-finished, and the evening moved at its own gentle pace. It was there that my teacher, Professor Syed Manzoorul Islam, introduced me to Mark Tully. There was no ceremony to the meeting, no sense of occasion. He smiled, shook my hand, and asked a question that was almost disarmingly simple. We began talking, without knowing how far the conversation would travel.

At that moment, I knew who he was in the way one knows certain names before meeting the person behind them. I was born after 1971. The war that gave birth to Bangladesh had reached me not as lived experience but as inheritance— through books, conversations, and the careful silences of those who had seen too much to speak lightly. I did not grow up waiting by a radio, tuning into the BBC World Service, hoping for clarity amid fear. And yet, long before I met him, I knew his name. It surfaced repeatedly, spoken with a particular seriousness, as though it belonged less to a journalist than to a moment when truth itself had been under threat.

Some names survive not because they were loud, but because they were trusted.

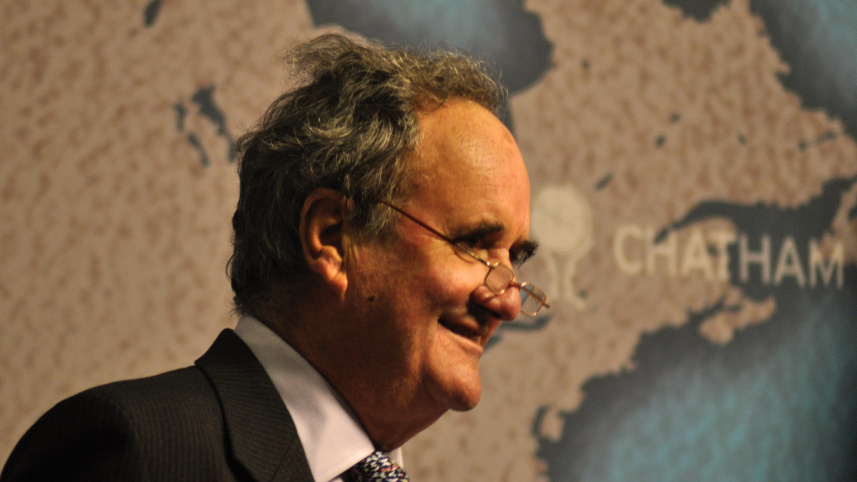

What struck me almost immediately was how little he seemed interested in speaking about himself. This was a man who had served for years as the BBC World Service’s South Asia bureau chief, whose reporting had shaped global understanding of the subcontinent, who had been knighted by the British Crown, awarded India’s Padma Shri and later the Padma Bhushan, honoured with a BAFTA, and formally recognised by Bangladesh as a Foreign Friend for his role during the Liberation War. Yet none of this entered the conversation naturally.

Instead, history entered quietly. I asked him about 1971.

I did not ask as someone seeking dramatic recollection, nor as someone testing historical claims. I asked as a journalist trying to understand what happens to truth when power is determined to erase it. Mark did not respond with certainty polished by time. He responded with memory— hesitant in places, vivid in others.

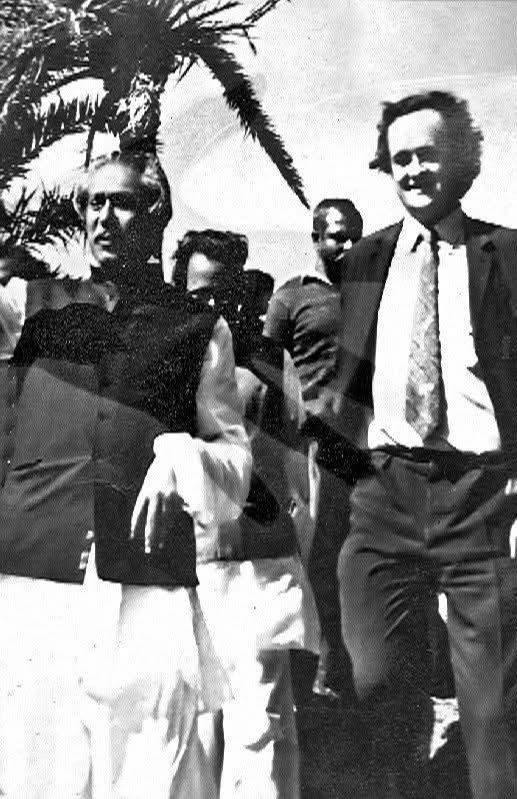

He spoke of March, of the suddenness with which violence overtook ordinary life. Of the Pakistani military’s swift attempt to suppress information, as if silencing journalists could undo reality. He spoke of the difficulty of verification when access was restricted and misinformation deliberate. He spoke of seeing Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, and Yahya Khan up close— not as figures frozen in textbooks, but as men navigating ambition, fear, and consequence.

As he spoke, it became clear that he was not interested in placing himself at the centre of events. His concern lay elsewhere: with responsibility. With the ethical weight of reporting when lies are institutionalised and silence becomes complicity.

He described refugee camps spilling across the Indian border, the scale of displacement defying numbers. He spoke of families who had lost everything, of exhaustion that went beyond hunger or fear. He spoke of the Mukti Bahini not in heroic abstraction, but as a lived reality of uneven resources and unyielding resolve.

Listening to him, I understood why Bangladesh remembers him.

Not because he was a foreign journalist. Not because he worked for the BBC. But because, at a time when the Pakistani military regime sought to bury the truth alongside its victims, his reporting refused to comply. When most foreign journalists were expelled and local voices silenced, the BBC World Service remained one of the few channels through which the world learned what was unfolding in East Pakistan. Mark Tully was among the journalists who made that possible.

There was a quiet dissonance in that moment. I was hearing firsthand accounts of a war I had never lived through, from someone whose professional life had been shaped by it. History, which had always felt distant and complete, suddenly felt unfinished— still breathing through memory.

At some point, the conversation turned towards me. In the course of it, I mentioned that I had studied at LSE, that the place carried its own quiet familiarity. He nodded, the gesture suggesting he understood without the need for further words. When I spoke of living in Dhanmondi, Dhaka, his expression shifted almost imperceptibly, sharpening with interest.

He began speaking about Dhaka after independence.

Not nostalgically, and not with the authority of an expert, but with the attentiveness of someone who had returned often enough to notice change. He spoke of watching the city grow, strain, adapt. Of how early optimism gave way to complexity. Bangladesh, to him, was not a story that ended in 1971. It was a living society, constantly reshaping itself.

He spoke, too, of resilience— a word often overused, but never casually. What he admired was not resilience as rhetoric, but resilience as practice: people rebuilding lives after devastation, navigating instability without illusion, continuing despite historical and institutional failure. It was a resilience he had first encountered during the war, and later recognised in the relentless movement of an independent nation.

That evening ended as such conversations often do— without closure.

We did not meet again in person.

Years later, during the COVID pandemic, I interviewed him virtually. He joined from Delhi, a city where he had spent much of his life. By then, he was well into his late eighties, but his mind remained alert, his curiosity intact. The conversation extended far beyond the allotted time.

We spoke about journalism in a media-driven world. I asked him how he viewed the relationship between traditional journalism and new media. He did not dismiss the latter, nor did he romanticise the former. Instead, he spoke about discipline. About how speed had replaced judgement, and reaction had displaced reflection. In his early career, slowness had been imposed by technology. Now, he said, slowness had to be chosen.

For him, the central crisis of contemporary journalism was not technological, but ethical.

Trust, he believed, was fragile. Journalism still mattered, but only if it resisted becoming an extension of power, outrage, or performance. He spoke of context, of historical memory, of listening before speaking. These were not abstract ideals. They were lessons learned in places where misinformation had real and often lethal consequences.

As the conversation drifted, we spoke about belonging.

Born in British India, educated in England, and shaped profoundly by decades in South Asia, Mark Tully believed it was possible to belong to more than one place without dilution. Britain was his formal home. India was where he had lived, worked, aged. Bangladesh occupied a different space altogether— not geographical, but moral.

I asked him whether one ever truly returns home after living elsewhere for most of one’s life.

He paused. Then smiled. It was not an evasive smile, but one shaped by acceptance. He did not offer a clear answer. He did not need to. The pause itself was an answer: that places change, that people change, and that the idea of return often survives only as memory.

Mark Tully’s career is often summarised through distinctions— long-serving BBC World Service South Asia bureau chief, knighted in 2002, recipient of India’s Padma Bhushan, BAFTA award winner, author of No Full Stops in India and India in Slow Motion, presenter of BBC Radio 4’s Something Understood. Bangladesh’s decision to honour him as a Foreign Friend sits among these recognitions as something different— not professional validation, but moral acknowledgement.

Yet knowing him, even briefly, I sensed his discomfort with summaries.

What mattered to him were moments when journalism mattered beyond institutions. When telling the truth was not a career choice but an ethical necessity. 1971 was one such moment, and it bound his life permanently to Bangladesh’s history.

Mark Tully has passed away, yet in every memory and every conversation, his presence remains vivid. I never heard his voice live on the radio in 1971. That belongs to another generation, to a different kind of listening— one shaped by fear, urgency, and hope pressed tightly against uncertainty. What I encountered instead, decades later, was the after-resonance of that voice: measured, thoughtful, unhurried, still attentive to the moral weight of words.

In an age where journalism often confuses visibility with value, his life stands as a reminder that the most enduring work is not always the loudest. It is the work that earns trust slowly, that refuses simplification, that understands when to speak and when to pause. For Bangladesh, Mark Tully will be remembered not as a foreign correspondent, but as someone who refused to look away when looking away was easier and safer.

For me, he remains a conversation.

A conversation that began in an old building at LSE and continued, years later, through a screen across continents. A conversation about truth, responsibility, and the uneasy relationship between home and distance. A conversation that never sought closure.

Some lives do not end with conclusions. They linger, asking us to listen better.

Farewell, Mark Tully.

Bangladesh will remember you.

Bulbul Hasan is a British-Bangladeshi journalist and writer with over two decades of experience across television, print, and digital media. He serves as the UK Correspondent-at-Large for The Daily Star.

Send your articles to Slow Reads for slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.