Jinnah vs Madani: The forgotten Muslim debate over Pakistan

In the wake of Bangladesh’s mass uprising of 2024, the partition of India in 1947 has re-emerged as a subject of renewed political and historical interest. A range of narratives has surfaced that seeks to frame the 2024 uprising not in continuity with the popular movements of 1971 or 1990, but instead by drawing parallels with the political moment of 1947. Some of these voices go further, presenting the events of 1947 and 2024 as part of a shared historical trajectory and claiming joint authorship of both moments.

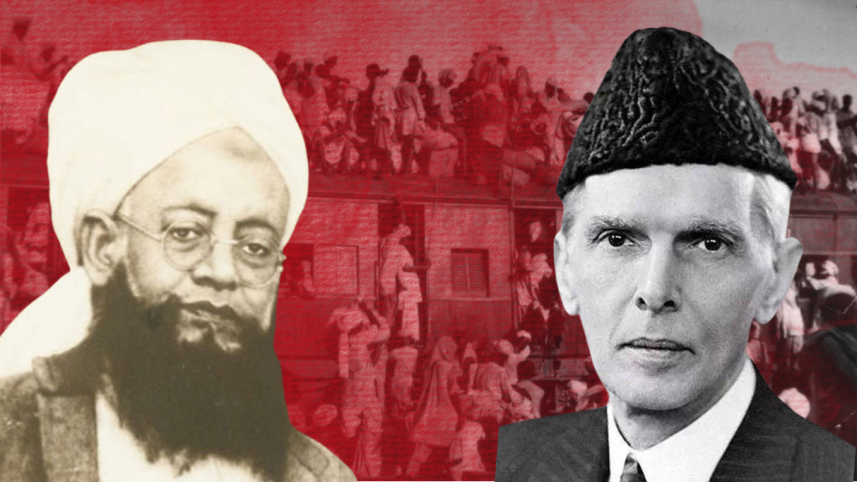

Against this backdrop, the noted researcher Altaf Parvez turns to the past to interrogate how Islamist parties positioned themselves during the creation of Pakistan in 1947. The first instalment of this series revisits a foundational yet often overlooked ideological confrontation over partition: the debate between M. A. Jinnah and Maulana Madani.

To the Jamiat and Maulana Madani, the Pakistan movement was a politics of division

There is no doubt that the chief architect of the Pakistan movement was M. A. Jinnah and the Muslim League. However, the origins of this idea do not lie solely with them. The word “Pakistan” did not appear in the Lahore Resolution. Well before that resolution, at the Muslim League’s 21st annual session in Allahabad in 1930, Iqbal proposed the idea of a “separate political space” for Muslims. In 1933, a joint publication by Chaudhary Rahmat Ali and three of his associates (Now or Never) presented a territorial vision called “Pakistan”, but even then the letter “I” was absent, and the aspirations of Muslims in Bengal and Assam for a separate state were not included.

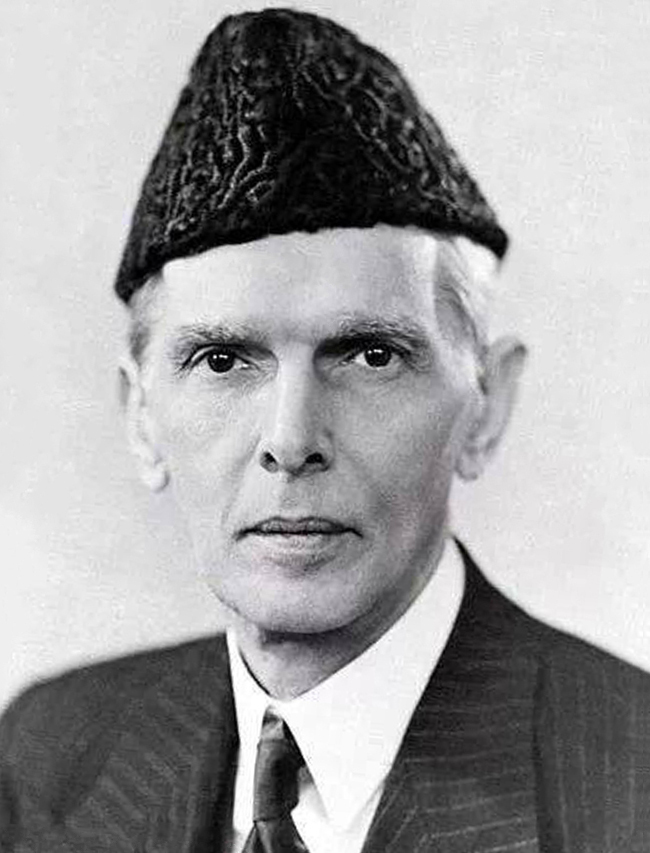

Jinnah’s emphasis on the idea of Hindus and Muslims as “two separate nations” began only after the elections of 1937, in which the League won just 111 out of 1,586 seats across the provinces—barely one quarter of the seats reserved for Muslims.

From this point onwards, Jinnah began to argue that, following any prospective independence of India, a democratic constitution and Western-style democracy would not be able to address Muslim demands. In a democratic political system, there was a credible fear that minorities would be ignored. The fear of Muslim subordination in a future India was, he argued, justified. Muslims, moreover, constituted a separate nation. They were part of a distinct civilisation. The unified cultural and spiritual consciousness required to form a single nation, he maintained, did not operate in the same way among Hindus and Muslims. The alternative, therefore, was a separate state for Muslims.

It goes without saying that this entire outlook was fundamentally different from Jinnah’s political discourse in his early years in Indian politics, and radically distinct even from the Lucknow Pact of 1916 concluded under his leadership.

After the elections of 1937, the Congress formed governments in several provinces and adopted measures that heightened Muslim fears of permanent subordination to a Hindu majority in a future India. Jinnah began to transform this fear into political capital. His new political vision entered the public arena through the Lahore Resolution. During this period, Jinnah also curtailed the autonomy of provincial branches within the party and centralised decision-making authority in his own hands.

When the Pakistan movement gained momentum and Jinnah entered the elections of 1946, other Islamic organisations were unable to compete with his party. Across the centre and the provinces, a total of 524 seats were reserved for Muslims in this election, of which League candidates won 453—many times more than their performance in the 1937 elections. At this time, with a few minor exceptions, the major Islamist parties and leading religious scholars opposed Jinnah and the Muslim League’s Pakistan movement. Among prominent religious thinkers, Maulana Maududi raised primarily theological objections to the League’s position. By contrast, Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madani and Abul Kalam Azad advanced cultural and political-strategic arguments. Maulana Maududi’s organisation later became today’s Jamaat-e-Islami.

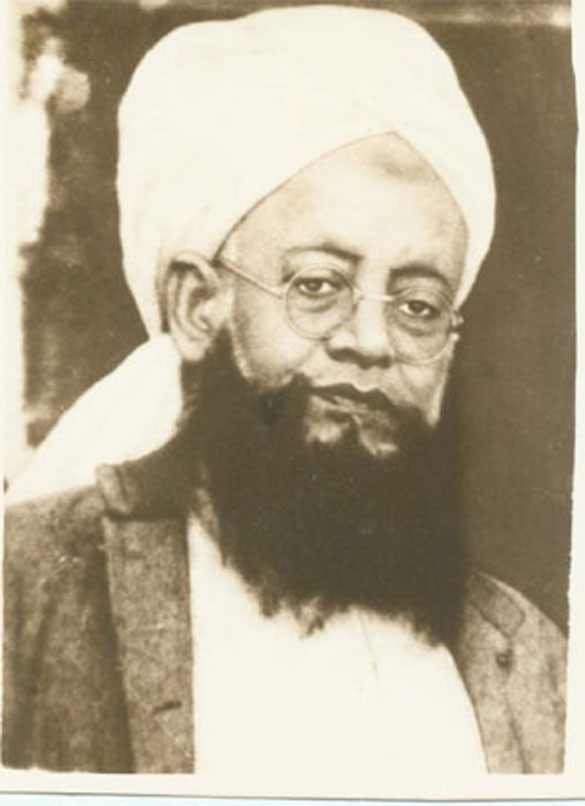

On the other hand, across India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, nearly all parties and sub-groups of the Deobandi tradition trace their organisational lineage to the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, founded by Maulana Madani in 1919. From 1938 onwards, Madani served for nearly two decades as the organisation’s third president, leading one of the most influential Muslim bodies in India.

Madani regarded the Pakistan movement as a politics of division. In his view, the development of the Indian subcontinent over centuries had taken place through the joint participation of Hindus and Muslims. In his words, “We were born in neighbouring societies, lived alongside one another, and shared many social advantages and disadvantages together.” (Maulana Husain Ahmad Madani, An Open letter to the ML, Trans: Dewan Ram Prakash, Lahore, 1946.)

For Muslims, he argued, the place of their birth established a deep organic bond with that land. They were simultaneously Muslims and members of a broader qawm that included non-Muslims, with whom they shared profound social ties. Together, they needed to stand against the real enemy—the British. The primary problem between Hindus and Muslims in India was British power, not each other.

According to Madani, after Mecca and Medina, India was the most precious place for Muslims. There was no contradiction between being a member of the ummah and living in India. He viewed the demand for the creation of Pakistan as a British project. Throughout his life, Maulana Madani not only opposed the League and Jinnah but also engaged in intense ideological debates with Maulana Maududi.

In short, at that time the Jamiat was advocating an undivided Indian political nationalism that stood above Muslim nationalism.

Against Madani’s Indian nationalism, Jinnah’s argument was that the historical interaction and proximity between Hindus and Muslims in Indian society existed only at the level of external social life. At a deeper level, the two communities had always maintained two distinct cultural worlds, whose core elements were not inclusive. Their ways of thinking and living had never truly merged into one. (S A Latif, The Muslim Problem in India, Bombay, 1939, p. 30.)

In the very year of the Lahore Resolution, a special conference—known as the “Azad Muslim Conference”—was organised by the Jamiat along with several other organisations to oppose the demand for Pakistan. So-called “nationalist Muslim” organisations were the main conveners of this conference.

In opposing the League and the Pakistan movement, the Jamiat also formed an alliance with the Indian National Congress. In 1930, the Jamiat formally passed a resolution declaring that “under the leadership of the Jamiat, Muslims will work together with the National Congress in the struggle for independence.” (Dr Mushtaq Ahmed, Shaykh al-Islam Sayyid Husain Ahmad Madani (in Bangla), Islamic Foundation Bangladesh, 2015, p. 219.)

Although Mufti Kifayatullah was formally the president of the organisation at the time, Madani was its principal driving force, and the above decision was taken under his chairmanship.

Even when the Congress eventually accepted the partition of India, the Jamiat maintained its opposition to the formation of a separate state, that is, the creation of Pakistan, until the very end. They formally reiterated this position at an official meeting held on 7 May 1947.

During this period, relations between the League and the Jamiat were extremely bitter. Many organisers of Islamist organisations opposed to the Pakistan movement, including the Jamiat, referred to Jinnah as “Kafir-e-Azam” and as Churchill’s “show-boy”. (Do You Know Who Called Muhammad Ali Jinnah Kafir-e-Azam And Why?, The Friday Times, Pakistan, December 29, 2023.) The originators of both these epithets were another Islamist group, the Ahrar.

In Bengal, the Jamiat was also a fierce critic of the governments of Khwaja Nazimuddin and Shaheed Suhrawardy. In particular, Madani portrayed the famine in Bengal during Suhrawardy’s tenure as the result of misrule by the League.

Maulana Hifzur Rahman Seoharvi of the Jamiat was an even more severe critic of the League than Madani. He argued that as the British were on the verge of losing Hindustan, they wanted to inflict damage on the country by using the League to take control of the ports of Karachi and Calcutta. He also claimed that Jinnah had left the Congress because the organisation had taken an anti-imperialist stance against British rule. To vote for the League, he argued, was to vote in favour of British subjugation. However, the 1946 election results testify to the fact that the Muslim masses did not pay much heed to such arguments. Even so, evidence of the Jamiat’s continued influence among Bengali-speaking populations after the election can be seen in the Sylhet referendum, where public opinion favoured the inclusion of some areas of the Barak Valley within Assam. This outcome was achieved through the active involvement of Deobandi scholars who were followers of Madani.

In order to manage the widespread opposition of pro–undivided India Muslim nationalists, Jinnah and the League had, from before the Lahore Resolution, been searching for allies within rival clerical camps. As a result of these efforts, a split emerged within the Jamiat-e-Hind by around 1945. Under the leadership of Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, the old Jamiat fractured and gave rise to a new stream called the Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Islam, which began to support the League’s Pakistan movement. This development helped overcome the League’s weakness within the religious-theological sphere.

Taking advantage of British favour towards them, League leaders at times even resorted to violence against the Jamiat. (A major example of such violence was the assassination of Allah Bux, the popular Chief Minister of Sindh, who had stood in the way of the Muslim League’s victory in Sindh.) League activists branded Maulana Madani and Maulana Azad as apostates (murtad). (Shamsul Islam, Muslims Against Partition of India, Pharos, India, 2023, p. 216.) Jinnah, for his part, referred to Azad as the Congress’s “show-boy”.

Altaf Parvez is a researcher specialising in history. The article has been translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles to Slow Reads for slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.