Raihan-Ghatak-Tarkovsky: We shall search, we shall find

“Eisenstein, Pudovkin / We shall fight, we shall win” was a chant by students of Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) during the 2015 student strikes. Their protests were against the appointment of a television actor-turned-politician as head of the film institute. This slogan invoked Soviet directors Sergey Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin, who proposed an idea of revolutionary cinema in the Soviet Union. That slogan reappears in a transformed meter as the title of Ashish Rajadhyaksha’s John–Ghatak–Tarkovsky: Citizens, Filmmakers, Hackers (Tulika, 2023), a vigorous history of public film education in India, which today manifests on vibrant film campuses that often encounter state-managed sanitisation. The first two names in Rajadhyaksha’s book title are Indian third cinema directors John Abraham and Ritwik Ghatak. On the walls of India’s film institutes, murals of both these figures are a typical sight (at Dhaka University’s Film & Television Department, Ghatak also appears on wall murals). Yet these majestic memorials exist alongside the uneasy contemporary reality– film schools that are increasingly run along anodyne, controlled vertices, with cinema’s original potential for radical change pushed far away. When I recently interviewed Zahir Raihan’s wife, actress Kohinoor Akhter Suchanda, she expressed a familiar sentiment– that cinema had once been an art form, a legacy vanished in the bustling contemporary.

I have thought of the John–Ghatak–Tarkovsky coupling while sifting through the uneven space of recovering Zahir Raihan’s legacy. While his portrait sits in the first-floor landing of the Bangladesh Film Development Corporation, our film industry is out of sync with the Raihan project of revolutionary cinema in his final years. In my new film A Missing Can of Film (2025), I attempt a dialogue with the absent figure of Zahir Raihan, and the punctum is a sequence where our camera glides up the stairs of FDC, past portraits of Raihan and Satyajit Ray. As the camera glides forward, it is interrupted, and then reverses itself, while on-screen supertitles propose that “angry” Ritwik Ghatak would have been a more appropriate pairing with Zahir Raihan. There are two concepts at work here– first, that if Zahir Raihan had lived, a very different film industry would have been birthed from 1972 onward; and second, if in spite of Raihan’s wishes the distorted film space we have today had prevailed, he would have rejected these “killing fields of cinema” (a phrase used by Catherine and Tareque Masud in a different context). The other punctum is the hallucinatory murder scene in Raihan’s Anwara (1967), in which I read the traces of Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925)– transposing a mutiny on a Russian battleship to a tangled family conflict in rural Bangladesh were the forms of internationalist cinema that Zahir Raihan was arriving at by the late 1960s.

Missing Can premiered at the Eva International– Ireland Biennial of Contemporary Art last year, and it is currently on view at the Kochi-Muziris Biennial of Art in India. Considering the internationalism of Zahir Raihan’s Stop Genocide (1971)– he invokes Auschwitz, Vietnam, Algeria, and Palestine through Alamgir Kabir’s narration– I spent my time in Ireland surveying what other forms of world cinema were being screened alongside my on-screen Raihan. In this process, I came across Eoghan Ryan’s Carceral Jigs (2025) where a ventriloquist’s puppet is the centre point for a meditation on the rise of a new form of Irish anti-migrant racism. Throughout the film, the puppet keeps reappearing, channeling dark and light, flopping around, never settling, never firm. In that physical apparition – one of the few elements to occupy the full 16:9 ratio of the video – I gleaned the presence-absence of a commitment to an accelerated editing rhythm, colour schema, and fluctuating ratio-proportions. We also encountered grainy surveillance of immigrant containment camps, a menacing dance floor in hyper-saturated VHS-like colour, and, at a repeating interval, furious mobs burning down homes for migrants.

There are two concepts at work here– first, that if Zahir Raihan had lived, a very different film industry would have been birthed from 1972 onward; and second, if in spite of Raihan’s wishes the distorted film space we have today had prevailed, he would have rejected these “killing fields of cinema” (a phrase used by Catherine and Tareque Masud in a different context).

This month in Dhaka, while organising screenings of Missing Can at the Liberation War Museum, Bengal Shilpalay, and the Dhaka University Film & Television Department, I have been thinking back to Eoghan Ryan’s staccato editing rhythm, and the way he slaloms between 4:4 archival and 16:9 contemporary, rather than the more typical approach of expanding archival footage to occupy the same screen span as the more recent footage. Walking into Eoghan’s space brought into intriguing contrast the slow, roaming shots of my own film and the frenetically exuberant pacing of his, both now unspooling to the same Irish audience. Missing Can includes the somnolent tracking style of my earlier film Jole Dobe Na (2020). The hushed silence of the Dhaka Film Development Corporation during my 2024 shoot (an echo of Kolkata’s dream-state hospital in the 2020 film) parallels my unresolved questions around Zahir Raihan and a particular nation-state-bound film history.

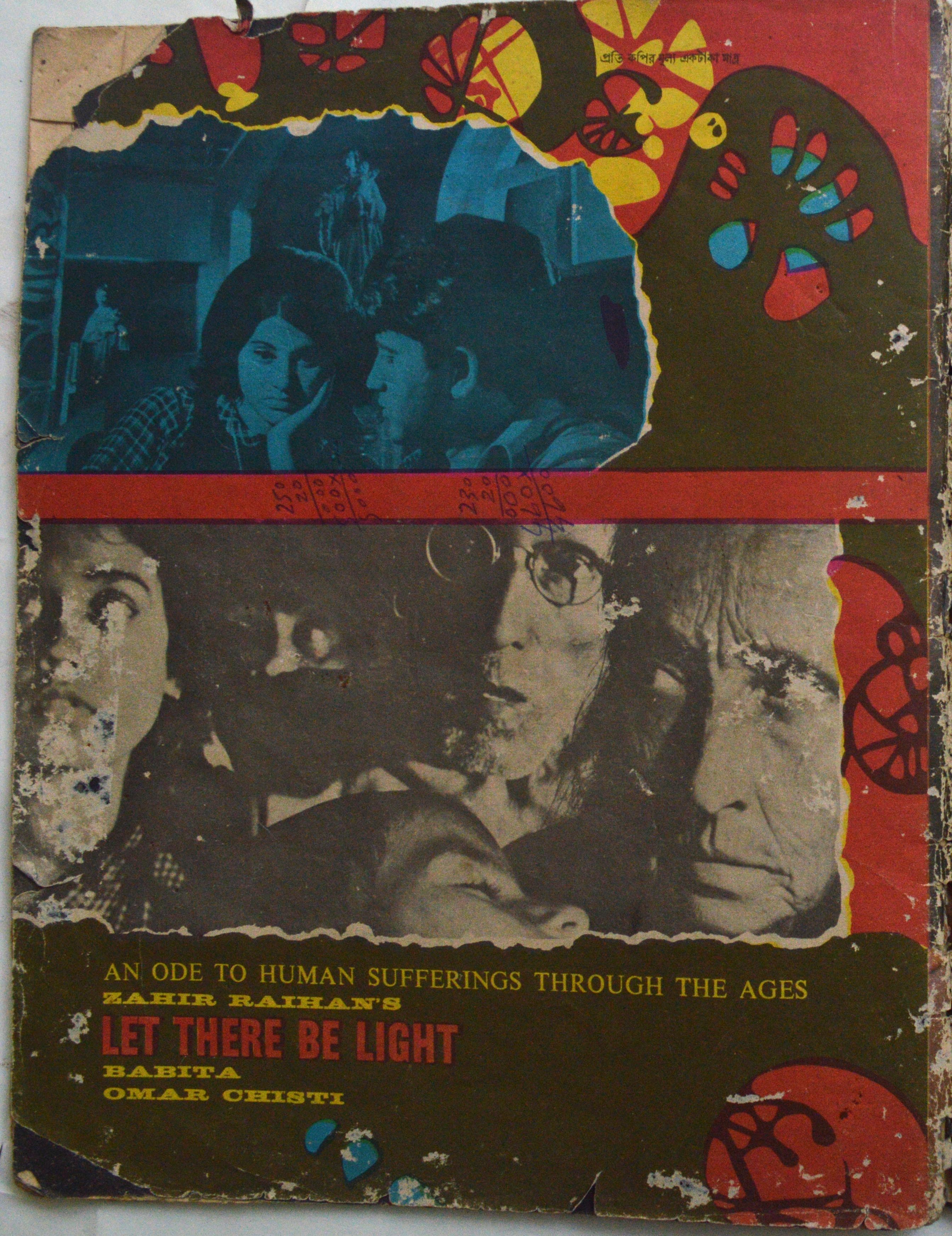

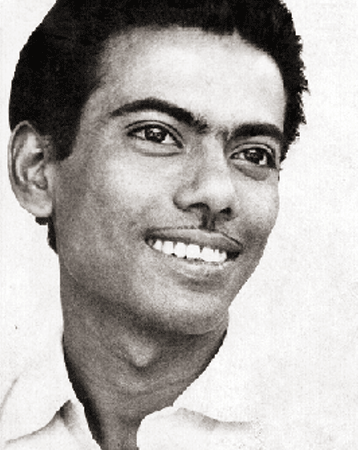

Zahir Raihan disappeared on January 30th, 1972, immediately after the Bangladesh Liberation War. He had set out to find his missing brother, novelist Shahidullah Kaiser, and was abducted in Mirpur. A restless polymath, he had directed and produced numerous films and written many novels. The tensions within his cinematic forms (from neorealist social realism to mass-popular entertainment), film dialogue (from Pakistan’s ‘Islamic language’ of Urdu to the Bangladesh national language of Bengali), and political alignments (from a nationalist project to the Soviet International) rendered him a cipher after death. We consider him a war martyr (shaheed), but he was abducted 45 days after the end of the fighting. In Missing Can I search for Zahir Raihan within his own film archive, and I supplemented my reading of his life through conversations with his family members (Kohinoor Akhter Suchanda, Farida Akhtar Babita, Tapu Raihan, Anol Raihan), film scholars (Mir Shamsul Alam Baboo), and Film Archive leadership (Farhana Rahman). These conversations are the foundation of my own understanding of his legacy, yet the search for Zahir Raihan is stymied by the absence of critical materials, including around his unfinished film Let There Be Light.

During the editing phase, I was in my own internal dialogue with the films of Molla Sagar, about whom I first wrote in The Daily Star in 2017 (“The cinema you were waiting for”). In Sagar’s new film Bhobar Vita (2025), for which I assisted with subtitles, he is on a similar quest for the legacy of Ritwik Ghatak. Interspersed with conversations with Ghatak’s twin sister, Sagar’s film attempts a “road movie” style journey through Old Dhaka, often with a GoPro camera that searches for traces of Ritwik Ghatak’s residence. That search faces current residents whose fear is that a documentary may result in some loosening of their own claims to the land they live on, often without paperwork. At the end of the film, Sagar provides a painful coda– the news that Ritwik Ghatak’s ancestral Rajshahi home was destroyed during the many conflictual events of post-uprising Bangladesh in 2024. The reader can understand how, while editing his subtitles, I experienced a flash of recognition around the ways that Zahir Raihan’s legacy has also slipped out of reach.

The posthumous ambiguity around Zahir Raihan circumnavigates the way he became a symbol for a nation-state project that he may have been critical of if he had lived. Dhaka’s film industry emerged from the war shattered by the murder of Raihan, who had held promise of what anthropologist Lotte Hoek called ‘cross-wing filmmaking’ within a period when ‘united’ Pakistan was about to split into two nations. Raihan started as an assistant director on Jago Hua Savera (The Day Shall Dawn, dir. A. J. Kardar, 1959), an early Pakistani neorealist production. Featuring East Bengali fishermen speaking an invented Urdu-Bengali patois, the film was a commercial failure. However, scholar Iftikhar Dadi argues that the film played a ‘spectral role in subsequent cultural developments’.

The two Raihan films that are relevant to trace his turning away from Pakistan are Jibon Theke Neya / Taken from Life (1970), made a year before the war, and Stop Genocide, completed at a feverish pace in the middle of the 1971 liberation war. Both films intercut documentary footage with filmed fiction. Newsreel footage and photographs of street marches against the Pakistan military junta are inserted between filmed scenes. Stop Genocide was completed during the war and faced what Alamgir Kabir (Film in Bangladesh, 1979) called a ‘paucity of filmic documents of [that] gruesome massacre,’ and responded, through montage and inserts, with ‘artistic stubbornness’. Mahmudul Hossain posits in The Other National Cinema of Bangladesh (2023) that Raihan had observed ‘Third Cinema’ and drew upon its use of documentary clips, newsreels, photographs, and statistics.

Masha Salazkina ends her book World Socialist Cinema: Alliances, Affinities and Solidarities in the Global Cold War (2023) with a close reading of Stop Genocide. She reads in Raihan’s approach a kinship he may have had with socialist filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein, Santiago Álvarez, and Andrzej Wajda. Yet, if we look at Raihan’s corpus from the 1950s until the Bangladesh war, he also made family dramas, commercial blockbusters, and one nationalist film. His family members recall that Let There Be Light was to be the film in which his affinity with direct cinema was finally going to find full expression– it was slated to be a film in multiple languages, including English and, possibly, Russian. In Missing Can, I wanted to trace the genealogy of Raihan’s brief, liminal socialist cinema, or what I call the ‘Socialist Stillborn’ formed under the crucible of a liberation war in which the communist parties were not allowed a central role. What type of socialist cinema did Raihan develop during that war year spent in exile in India? What earlier tendrils of this had he concealed within productions while having sympathy for left politics? What future Bangladesh socialist cinema might have been birthed if Raihan had survived the war and moved forward with his proposal (co-authored with Alamgir Kabir and Syed Hasan Imam) for a nationalised cinema industry?

I spoke to Eoghan Ryan about some of this, and he highlighted the work of ‘unpack[ing] a life not lived but presumed, through detritus and intention; compelling the dead to speak’. Over an afternoon conversation, I asked him if he made a differentiation in his editing choices between footage of the quietly confident Irish immigrant who speaks of gardens with many flowers, and the covert video material of white ethnonationalists he spliced together. Though inconclusive, I cited the difference between Walter Heynowski and Gerhard Scheumann’s Der lachende Man (The Laughing Man, 1966), in which the interviewee mistakenly thinks he is among ‘friends’, and Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing (2012), where Indonesia’s executioners embrace the restaging of their crimes with gusto and a lack of remorse. What could a similar method be for the messy, unresolved narrative left behind by a mysterious abduction in 1972?

Missing Can projects my own simmering hesitation to break free of the path of quiet viewing. The editing pace quickens only when it comes to Raihan’s own films, sometimes mixed as three scenes per screen, to create a split-screen homage to John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix (1966). Then, as the jumpy rhythm of those scenes ends, we politely return to the Film Development Corporation (FDC). The red text on screen queries the artifacts in the FDC buildings – the Ray-Raihan portrait stairway, the rusted reel-to-reel machines, and the underused sound stages. These scenes from an enervated film industry sediment into a gentle critique that sits alongside Raihan’s own lifelong desire to challenge icons and deities.

Naeem Mohaiemen is Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Visual Arts, Columbia University, New York. He can be contacted at naeem.mohaiemen@gmail.com

Missing Can of Film can be viewed online for a limited period at these links.

Bangla: https://vimeo.com/user1938880/raihanbangla

English: https://vimeo.com/user1938880/raihan

Send your articles to Slow Reads for slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.