After billions spent, still gridlocked: What the new government must do

The Daily Star: What should the upcoming government immediately do to make Bangladesh’s communication infrastructure—particularly in Dhaka—functional beyond just building more roads and megaprojects?

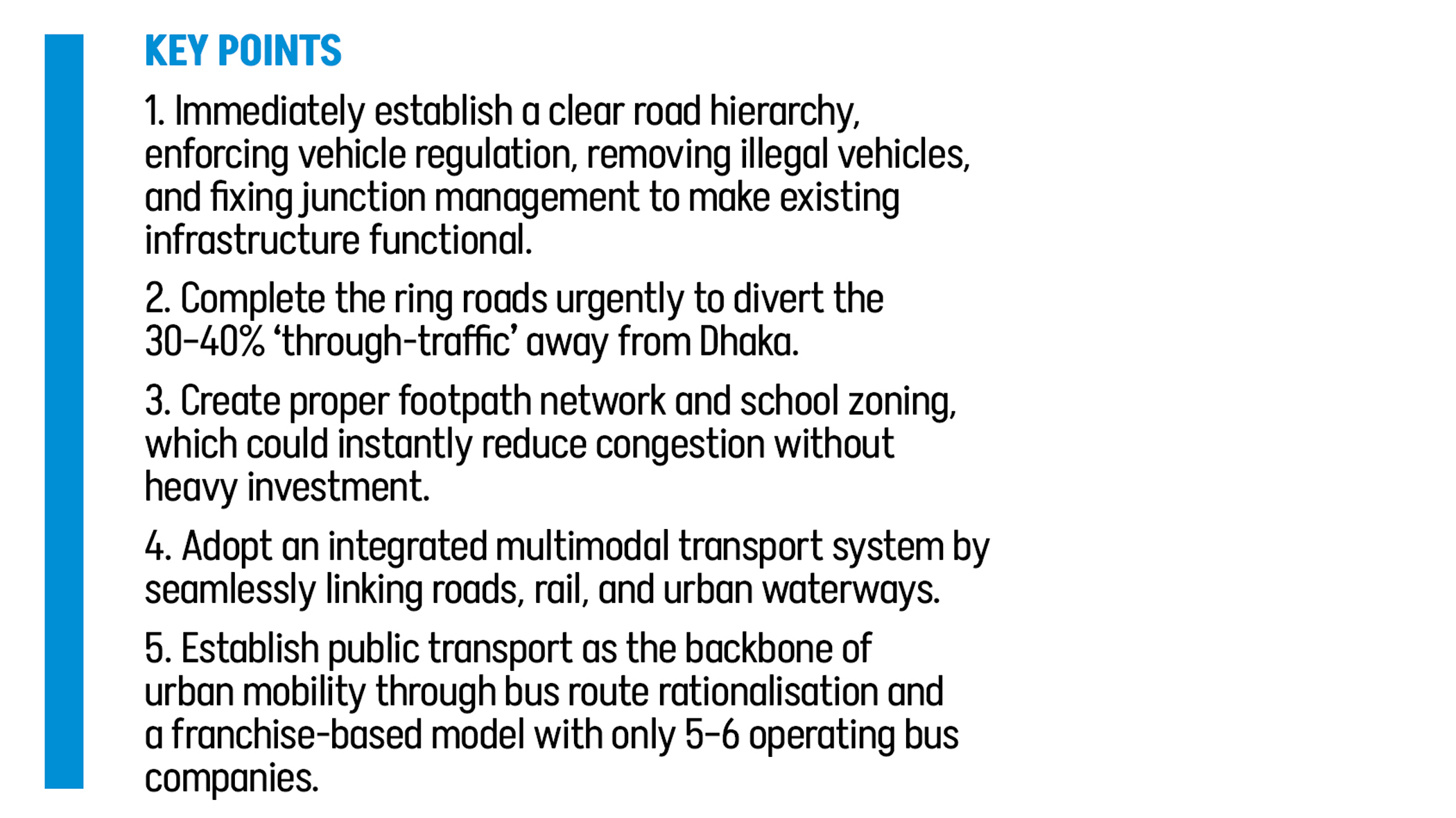

Md Hadiuzzaman: To make our existing road network functional, an immediate priority of the new government should be management and enforcement. It is tragic that, even after all these years, Dhaka still lacks a clearly defined road hierarchy. Within the city’s roughly 3,000-kilometre road network, we must first determine the function of each road—which ones are meant for mobility and which for accessibility. Without this classification, it is impossible to decide what types of vehicles should operate on which roads, or to what extent.

Establishing a road hierarchy is something that can be done immediately. It is not an investment issue; it is a matter of commitment. Once the hierarchy is defined, vehicle types, speed limits, and spheres of movement can be clearly set for each road. Simultaneously, it can also be enforced to remove unregistered, unlicensed, and illegal vehicles—especially from primary roads, whose main function is mobility.

Over the years, massive investments have been made in roads and flyovers with the sole objective of creating mobility. Yet we continue to fail because illegal vehicles prevent roads from functioning as intended. We have built around seven flyovers in the past decade and added expressways as well. However, these grade-separated structures must eventually meet the ground, where their effectiveness depends on how well intersections and junctions are managed.

I often describe intersections and junctions as the “heart” of the road network. Just as the heart pumps blood through veins, junctions direct vehicles in different directions. If, after defining the road hierarchy, we manage junctions properly, many traffic problems will be resolved. Again, this is a question of commitment, not investment. Why should illegal parking exist at every junction? Why should ride-sharing hubs cluster at crossroads? Why should illegal or non-motorised vehicles such as rickshaws and auto-rickshaws occupy these critical points? If the “heart” does not function, widening roads will achieve little.

For roads to function, vehicles must be able to move freely. Yet pedestrians are often forced onto the roads because footpaths are occupied or unusable. Despite investing hundreds of thousands of crores, the output remains poor. Dhaka has only about 3,000 kilometres of roads, of which just 200 kilometres are primary roads. It is entirely feasible to create a high-quality footpath network across the city.

Around 25 million trips take place in Dhaka daily, and nearly 25 percent people walk to their workplaces. Yet nothing has been done for them. Of the roughly 400 kilometres of footpaths in Dhaka, 60 percent are occupied and 40 percent are not walkable. With only an investment of around Tk 3,000 crore, Dhaka could have an excellent footpath network—keeping pedestrians off the road and allowing traffic to flow smoothly.

Another urgent issue is the absence of a functional mobility network due to hybrid trip patterns, where office and school trips collide on the same roads. In developed cities, school trips are typically separated from office commuting. Dhaka urgently needs a school zoning system with defined catchments so that students do not have to travel across the city—for instance, ensuring that a child living in Motijheel does not have to attend school in Uttara. Our research shows that 20 percent of trips in Dhaka are school-bound. Removing even this 20 percent from main roads would significantly ease congestion. This too requires commitment, not large investments. There are lots of examples to draw from to implement the school zoning concept.

Finally, Dhaka lacks any fully functional ring road. Most major roads here are aligned north–south, while the concept of peripheral ring roads exists largely on paper. Both the Strategic Transport Plan (STP) 2005 and the Revised Strategic Transport Plan (RSTP) 2015 clearly outlined an 88-kilometre inner ring road, followed by middle and outer ring roads. Yet, these remain incomplete. As a result, an estimated 30–40 percent of traffic in Dhaka is “through traffic”—vehicles merely passing through the city to travel from north to south of the country without any destination in Dhaka. The new government should urgently prioritise completing the inner and middle ring roads, which have already been partially implemented. As long as the full ring is not completed, north–south traffic will continue to pass through Dhaka, further worsening congestion.

It is particularly unfortunate that major infrastructure such as the Padma Bridge and the Dhaka–Mawa Expressway were completed without first completing the ring road system. The ring roads should have been operational before the expressway so that traffic travelling between North Bengal and South Bengal could bypass Dhaka altogether. Instead, we have rapidly funnelled even more traffic into the already overburdened city.

The inner and middle ring roads were partially implemented but failed to progress to a stage where through traffic could realistically avoid entering Dhaka. Additionally, the Dhaka Elevated Expressway was meant to connect with the Ashulia Expressway. If this connection is completed, the need for vehicles to enter the city would be significantly reduced.

Rather than initiating new megaprojects, the government should focus on completing these critical, half-finished projects. Partial implementation does not deliver real benefits. Cities such as Shanghai, with three ring roads, and Beijing, with seven, demonstrate the importance of such infrastructure. Dhaka, despite its population pressure, has none. As long as all highways remain Dhaka-bound, traffic issues will persist.

These five priorities are ultimately matters of political commitment, management, and enforcement—not investment.

TDS: Despite heavy investment in transport infrastructure, congestion keeps worsening. Where has planning gone wrong, and what policy corrections are most urgent?

MH: I believe our policymakers have failed to understand priorities and opportunities. There is often greater interest in projects where more money can be spent, rather than in addressing root causes. Dhaka generates nearly 2.5 crore daily trips, and traffic congestion of this scale cannot be solved through road-based transport alone. The next government must seriously think in terms of “integrated multimodal transport”.

Dhaka is naturally blessed with a river loop of about 110–112 kilometres, formed by the Buriganga, Turag, Shitalakkhya, Bangshi and the Tongi canal. We must utilise this asset. We frequently talk about “sustainable transportation,” but policymakers need to understand what it truly means. Sustainable transport ensures long-term returns on investment and accessibility for all. River transport, in this context, is the cheapest and safest option.

However, previous circular waterway initiatives failed because they focused only on purchasing boats and vessels without proper planning. Integrated multimodal planning is essential. It is not just about water transport; it requires identifying appropriate landing stations, ensuring seamless connectivity with road networks, and addressing challenges such as river pollution, siltation, and low bridges with inadequate headroom. If this river loop is properly utilised, road traffic pressure will reduce significantly.

The concept of a “Blue Network,” which is included in the Detailed Area Plan (DAP), remains largely on paper. If implemented, it could connect rivers, canals, and lakes within the city into a 550-kilometre network. In a city where even a 10-kilometre new road is nearly impossible, this offers a massive opportunity and could offload 30–40 percent of road traffic. But again, simply buying boats without an integrated plan will only lead to another failed project.

We can also draw lessons from cities like Kolkata, where a million people arrive at Howrah Station every morning, use the Metro, and return home via commuter trains. A similar synergy between MRT and commuter rail could reduce the need for people to live inside Dhaka. While we have undertaken many megaprojects, seamless connectivity is missing, and several projects remain partial. If the MRT Line 6 that goes towards Kamalapur is connected to commuter routes towards Narsingdi, Gazipur, and Narayanganj, the system would be far more efficient.

Our planning remains fragmented. We damaged a major highway for a BRT project while failing to launch a functional commuter rail system between Dhaka and Gazipur. Dhaka is a mature city; we cannot widen roads endlessly. We inherited a strong rail network from the British and an excellent river loop from nature. The new government must prioritise integrating and utilising these assets properly if we truly want to make Dhaka liveable.

TDS: How can vehicle regulation and the public transport system be strengthened more in fixing Dhaka’s mobility crisis, and what policy actions should be prioritised?

MH: Vehicle regulation is not only about numbers; it must also consider vehicle types and areas of movement. The number of vehicles must be proportionate to road capacity. Planners often say that a city needs 25 percent road space to be livable, but I disagree. With a strong public transport system, a city can remain livable with just 7–8 percent road space.

This is where the new government has a major opportunity. What we currently call public buses in Dhaka cannot truly be described as public transport. Public transport must be schedule-based and frequency-based, which our buses are not. Metro rail qualifies as public transport precisely because it follows a defined schedule and frequency.

We can learn from Singapore, where registration policies ensure that vehicle numbers never exceed 70 percent of road capacity, reserving 30 percent for future generations. For every new vehicle registered, one old vehicle is removed. In Dhaka, however, the number of vehicles is estimated to be eight to ten times higher than road capacity, compounded by illegal, unregistered, and unlicensed vehicles. This is why establishing a proper road hierarchy is essential, as it allows for science-based regulation.

Globally, cities are shifting towards research-driven transport systems, but we are living in a fallacy. Our roads have become sites of informal job creation and dumping grounds, which undermines functionality. Roads cannot compensate for the government’s failure to create jobs. Keeping roads overburdened ensures that even large investments fail to deliver results.

Transport development must follow stages: functional footpaths first, then public transport, followed by BRT, and finally MRT. Developed countries followed this sequence. We tried to impose advanced systems on top of a chaotic base, and unsurprisingly, productivity suffered.

Public transport works as the backbone for any city, then MRT is built on top as a high-capacity layer while public transport works as a feeder system. Because we lack proper feeder systems, MRT stations are now surrounded by informal transport such as ride-sharing vehicles and battery-run or paddled rickshaws. Our public transport system is so poor that informal transport ends up competing with buses—something virtually unheard of anywhere in the world. Informal modes are not compatible with buses and we must address the root cause here.

In Dhaka, only about 200–250 kilometres of roads are suitable for buses, out of a 3,000-kilometre road network, other roads are too narrow for buses to enter. So, there is no need for thousands of buses, routes, and owners for such a limited network. Currently, there are around 300–350 bus routes, which is far beyond what is required. The system cannot be fixed unless this is addressed.

We need bus route rationalisation and a franchise model with only five to six companies, as seen in developed cities and neighbouring countries. This is not a technical challenge—it is a political one. We are investing Tk 3–3.5 lakh crore in a metro system that carries only about 20 percent of passengers, while a dysfunctional bus system already carries around 40 percent. Our research shows that with just Tk 5,000 crore, we could introduce a fleet of modern double-decker, low-floor, air-conditioned buses like those in London.

If we had 40–42 rationalised routes operated by five to six companies, Dhaka could have an excellent bus network. Once road transport is properly functional, metro expansion can ensure seamless connectivity. Fragmented projects without a network concept will never deliver efficiency.

Regulation must also distinguish between mobility and accessibility. Some roads are high-speed mobility corridors and should not allow slow or unfit vehicles, while others serve accessibility. Vehicle types, routes, and numbers must be regulated accordingly.

Our research suggests that if public transport truly becomes the backbone, it could carry 50–60 percent of passengers, reducing reliance on private vehicles. Combined with MRT, this would create a smooth network—something currently missing.

Finally, coordination with regulatory bodies is crucial. Roads are built by City Corporations or RAJUK in the case of Dhaka, while vehicle registration is handled by BRTA, often without much idea of road capacity. Anyone with money can buy a car, but this cannot continue. Numbers of registered vehicles must be proportionate to our road capacity.

Additionally, traffic management through hand signals is outdated for a city with metros and expressways. We must move towards digital signalling, but that will only work after regulating vehicle types, numbers, and routes. Digital signals are not a magic solution—they require prerequisites and time. People have almost forgotten that they should be mindful of signals while driving, and that behaviour change will not happen overnight.

TDS: Is widening existing highways an effective strategy for long-term mobility, or should Bangladesh invest in a separate, access-controlled mobility network, and how realistic is this for Bangladesh right now in your opinion?

MH: Our existing highway network is primarily designed for accessibility, and in my view, we cannot simply widen highways from two lanes to four or six and expect them to function as mobility networks. Take the Dhaka–Chattogram Highway, for example. It is now being planned as an eight-lane road, but widening alone cannot transform an accessibility network into a high-speed mobility corridor.

Whenever we widen roads, we create development-induced displacement, which has serious social and economic consequences—business losses, joblessness, land loss, and social marginalisation. We have already seen this with the Dhaka–Mawa–Bhanga Expressway. Despite being an expensive project, it gained a poor reputation due to frequent accidents. In trying to convert existing roads by breaking and rebuilding them, we are destroying valuable assets, yet they are still not working as intended.

If we want to develop controlled-access mobility networks, challenges are inevitable, especially land constraints. However, we must carefully assess the costs of widening or dismantling existing roads—particularly the displacement they cause—and compare them with the land acquisition, capital costs, and investments required to build a new network. This feasibility analysis must begin now.

All our national highways are Dhaka-bound, following a radial pattern. While this provides accessibility, it does not create a true mobility network. If we want to accelerate economic and GDP growth, we must think beyond passenger movement. Where are our freight corridors? Currently, passengers and freight share the same routes, which is highly inefficient. Without dedicated freight corridors, mobility and economic efficiency suffer.

Most developed countries have separate economic or freight corridors. Although the Dhaka–Chattogram Highway has been widened to four lanes, it has not become an economic corridor. Simply widening an accessibility road does not achieve that—and widening it further is unlikely to change the outcome. If freight cannot move efficiently, passenger transport alone will not drive economic growth.

It is time to seriously weigh the costs and benefits of creating dedicated mobility and freight networks instead of repeatedly widening existing roads. This requires feasibility studies, land acquisition planning, and long-term investment—but continuing the current approach is already causing displacement without delivering efficiency. The new government must begin this planning now; delaying it will only make future implementation more difficult.

Finally, true mobility networks must be controlled-access corridors. Markets, schools, and other roadside developments cannot coexist along such routes. Otherwise, accidents and congestion are inevitable—as we are already witnessing today.

TDS: What reforms are needed within institutions like the Planning Commission to ensure communication projects are professionally evaluated, policy-driven, and aligned with long-term mobility goals rather than short-term political considerations?

MH: The Planning Commission has a wide mandate, but the way it currently functions lacks efficiency. At present, project-implementing authorities approach the Planning Commission only at the final stage for approval, which reduces the process to a formality. However, the Planning Commission’s role should go far beyond approval. It should prioritise projects based on actual needs, especially since it has a comprehensive view of who is doing what across sectors.

While different authorities may propose projects, the Planning Commission should have the ultimate decision-making power. I believe there should also be periodic reviews even after approval. Currently, projects return to the Commission only when there is a request for time extension or cost escalation. Instead, the Commission must have the authority to oversee, monitor, and hold implementing agencies accountable throughout implementation to prevent the overruns we see so often. Project initiation, approval, and monitoring should be led by the Planning Commission—because planning is its core responsibility, not just approval.

A major challenge is the lack of professional planners and technical capacity within the Planning Commission. It oversees projects nationwide, but without sufficient technical expertise, it cannot properly evaluate feasibility studies or hold implementing agencies accountable. Often, one authority plans a project without knowing another authority is planning something nearby, leading to conflicts during implementation. This is precisely why project initiation must come from the Planning Commission, which has a holistic view of water, rail, and road projects across the country. Strengthening technical and professional capacity within the Commission is essential.

Post-evaluation of projects is also critical. Many projects have failed to meet their financial or economic expectations, and without learning why, we risk repeating the same mistakes. There is also a misconception about “mega projects.” A project is not mega because of the size of investment, but because of its impact—it improves living standards of thousands of people, creates jobs, and accelerates economic growth.

Additionally, I want to emphasise that the new government must urgently work towards capital relocation or administrative decentralisation. Dhaka occupies just 0.2 percent of the country’s land but accommodates 15 percent of its population. This imbalance cannot be fixed by more projects in Dhaka. Claims that projects will “reduce traffic congestion” in the city are misleading, because new projects in the city only attract more people.

Many countries have taken bold steps. India has shifted its capital three times, while Pakistan, Malaysia, and Indonesia have also relocated their capitals. Indonesia’s capital is twice the size of Dhaka but has half the population. It has already passed legislation to move its capital from Jakarta to Borneo. That is forward-looking policy, and our policymakers must think the same way.

We cannot continue concentrating investment in Dhaka, which already generates 40 percent of GDP. Demand and supply will never balance this way. The new government must prioritise job creation in other districts and economic zones so people do not need to migrate to Dhaka. Even if capital relocation is not immediately possible, administrative decentralisation—relocating institutions that do not need to be in the capital—must begin now. Redirecting population flow away from Dhaka is no longer optional; it is urgent.

The interview was taken by Miftahul Jannat and transcribed by Ystiaque Ahmed.

Md Hadiuzzaman is a Professor in the Department of Civil Engineering at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET)