When policy lacks a development philosophy, failure follows

Every elected government sets certain goals once it comes to power. Most of the time, these stated goals sound impressive. They literally set expectations among the citizens. When governments fail to meet those expectations within a few years, dissatisfaction grows among the public. In this scenario, we regularly see that election pledges have little influence on voter decisions. Instead, people come to trust their chosen government when their quality of life improves. Those state initiatives that may swiftly bring about improvements in the level of living lay the foundation for a government’s legitimacy.

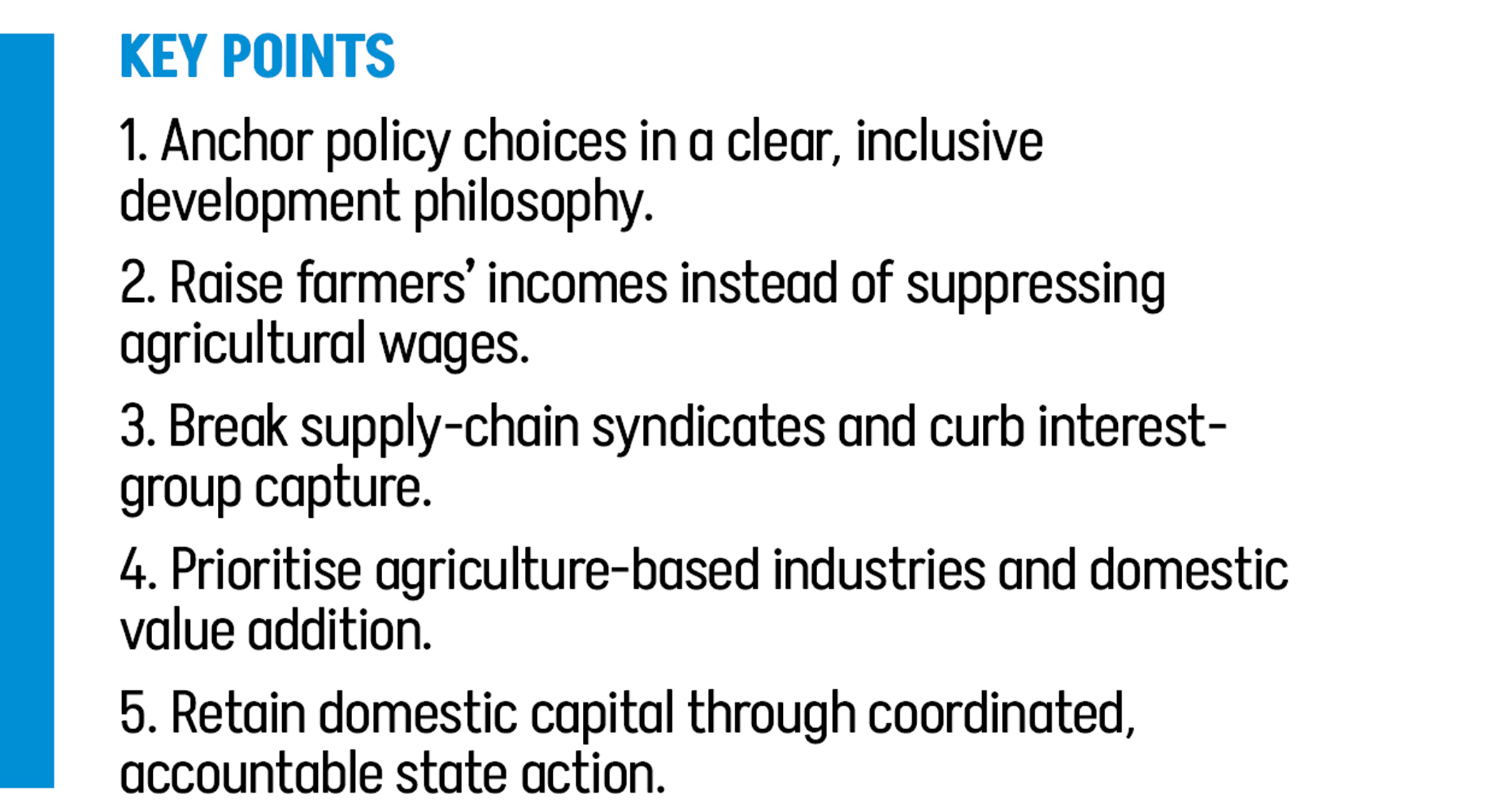

The new government’s priorities following the election should be determined by its development philosophy. Regardless of whichever party takes power, some populist demands persist, such as lower commodity prices, higher purchasing power, and increased employment. However, these are not inherently development philosophies. These commitments are the outcome of a development philosophy. A development philosophy answers questions such as, “For whom is development?” What type of development? And “How could progress be achieved?” In other words, the questions are: how will employment grow? How will inflation go down? How will people’s incomes increase? Because in a market system, none of these things can be controlled without government intervention. If there is a war, a natural disaster, or a pandemic, all countries are affected to some degree. A country’s economy is regarded as stronger if it has a higher economic capacity to swiftly use its own resources to satisfy its residents’ primary needs.

In today’s capitalist economy, greater emphasis is placed on efficiency and productivity, be it manufacturing, agriculture, or services. Efficiency is important, but efficiency can be achieved in numerous ways. The more important question today is how to achieve efficiency and at what cost. When discussing development, economists currently argue that foreign investment should be increased, new factories should be built, cheap local labour should be used, exports should expand, and remittances should be increased. Apart from this discussion, there is virtually little debate about development. The reason for this is that a large section of economists has been indoctrinated to believe that we only have competitive advantages in industries where cheap labour can be employed and profits can be maximised. We must go beyond these repetitive platitudes. We must question why, over the previous fifteen years or more, while our guiding force was achieving efficiency, the country’s wealthiest have become richer and poverty has risen once again.

During the interim government, we observed how various interest groups created resistance against reform initiatives. The syndicate in the agricultural supply chain could not be eradicated. We noticed how the market was dominated by a few edible oil importing companies, and the government had little influence over them. We observed that rental and quick rental power plants, built through a government–business nexus, have not been shut down. Despite the fact that rural electricity reform is desperately required, we saw how contractors and businesses colluded with the Rural Electrification Board to impede reform. We discovered that merely subsidising fertiliser is not sufficient. If dealers are not monitored, farmers do not benefit from subsidies. Even with a 70% subsidy for agricultural mechanisation, marginal farmers could not access the machinery. Brokers acquire agricultural equipment using farmers’ identities and sell it at higher market prices, while farmers fail to receive the subsidy. As a result, we already know where the barriers to reform lie and why cosmetic initiatives are ineffective. We have come to realise that without keeping these varied interest groups under control, reform will not be possible. Therefore, the real task is not making a checklist of what to do, but identifying how to do it.

In the five decades since Bangladesh gained independence, a wave of new technologies has transformed the agricultural landscape. As the population grows, so too does our agricultural production. The push for greater production capacity has led to an increased dependence on chemical fertilisers over organic alternatives. With growing dependence on pesticides, our food is increasingly contaminated by harmful chemicals in the water. Farmers are facing rising health risks from fertilisers and pesticides, while toxic chemicals in food endanger public health nationwide. Seeds are being commercialised, yet escalating prices are burdening farmers with higher production costs. The rising need for irrigation has highlighted the importance of utilising surface water, alleviating the strain on groundwater supplies. Recent advancements in irrigation technology are transforming agricultural practices. The demand for innovative technologies to preserve agricultural products is on the rise.

Despite all these technological advancements, farmers’ quality of life has deteriorated even further. Production costs have surged, compelling farmers to sell crops at a loss. Farmers not only battle harsh weather but also suffer from unfair market prices. They face escalating production costs and delayed crop sales, forcing them to rely on high-interest loans to manage expenses.

Failure to repay loans on time forces individuals to seek additional loans from other NGOs to cover their obligations. Farmers ensnared in debt often abandon their land, migrating to cities as transient labourers. For many, daily labour or pulling rickshaws to settle debts takes up a considerable part of their existence. Children are being denied access to education. The burden of debt has driven some individuals to tragic ends, including suicide. Therefore, we need to make a choice: should we increase efficiency by ensuring higher income and greater security for farmers, or should we try to decrease production costs by lowering agricultural wages?

Bangladeshi farmers, living on the frontlines of climate disruption, are pioneering solutions that are shaping a new blueprint for survival. File Photo: Palash Khan

In Bangladesh, so far, the marginalisation of farmers has helped maintain a steady flow of cheap labour to urban areas and migrant labour abroad. The emigration of our youth in search of jobs abroad brings back valuable dollars, bolstering our reserves amidst rising unemployment. Much of this funding is allocated to cover substantial mega-project loans and to support imported energy costs. Development narratives have long centred on mega-projects and large-scale infrastructure initiatives. Despite the Sheikh Hasina administration’s plans for 100 special economic zones, leading to significant land acquisitions, investment remains elusive. High production costs, driven by soaring electricity and gas prices, are significantly dampening potential growth in the industrial sector. In the future, a significant imbalance may persist between supply and demand. Decisions are made erratically, without considering long-term consequences. Often, these decisions are made to serve the interests of some dominant interest groups. In such cases, the absence of coordination leads to spending billions of takas with no beneficial outcomes for farmers. On the other hand, those who need capital do not have access to it.

The next government must prioritise addressing the coordination issues. The agricultural sector requires alignment with an integrated development philosophy, rather than a mere checklist of tasks. Making inconsistent policy choices will not address the real issues. The agricultural sector must evolve in tandem with the industrial sector for balanced growth. The shrinking agricultural land and the transformation of farmers into transient labourers threaten the potential for a robust consumer goods market in this country. The nation’s industrial growth hinges on fostering local industries alongside export-oriented production. It is imperative that we prioritise agriculture-based industries. The garment industry heavily relies on imported raw materials, while agriculture does not. In the case of the garment industry, the nation’s input is confined to the value added by its workforce. On the other hand, agriculture-based industries, such as jute and sugar, have different layers of value addition. Unfortunately, these sectors have experienced a steady decline over the last two decades.

When a nation relies entirely on foreign raw materials, it undermines its own economic stability. Such circumstances foster chaos and unpredictability. For example, the government’s failure to control commodity prices highlights its subservience to market forces. If domestic industries decline, Bangladesh will risk becoming overly dependent on imports, jeopardising its economic stability. Rising import and export costs will only exacerbate the government’s diminishing control over the economy.

The next government must prioritise building an economic base for the country. Over the past five decades, the sources of capital have been bank loans and the surplus from unscrupulous and unethical practices. For capital accumulation in the country, domestic sources of capital are also necessary. If the profits from foreign investment do not get reinvested and instead leave the country, there will be a continued shortfall of domestic capital. There must also be discretion regarding foreign investment opportunities. Not all sectors are equal. We need to think about how to keep domestic capital within the country. In this regard, it is urgent to increase farmers’ incomes. When farmers’ incomes rise, they can contribute to the economy as consumers of many domestic products, and reinvestment of surplus can also contribute to capital accumulation in the country. Instead, in our country, NGOs and microfinance institutions are benefiting. Farmers are being exploited from all sides only to generate capital for others. The government must take initiatives to improve farmers’ healthcare and gradually introduce a pension system for farmers.

It should be remembered that there have been technological advancements over the past fifty years. Technology can be utilised to improve farmers’ living standards. There was a time when sugar mills incurred losses as farmers were reluctant to supply sugarcane because they did not receive timely payments. Now, with various digital technologies, there is an opportunity to ensure that they receive their dues on time. Many of the crises in sugar mill management can now be addressed through investments in technology, allowing for more efficient management. There are now various ways to ensure accountability that did not exist before. In marketing agricultural products, technology can be used to ensure farmers receive fair prices. In all these areas, the government can form committees to review and plan anew.

For a long time, certain memorised knowledge and ideas remained acceptable, while anything that builds national capacity remained neglected and rejected. Without considering the changes of the past few decades and assessing the real needs, policies have been highly influenced by external actors. The new government’s task will be to prioritise exploring new ideas, conducting experiments, and encouraging innovations in every sector. However, this does not mean that these actions should be taken on a massive scale without scrutiny. Instead, they should start on a small scale, with coordinated planning to gradually address each complexity.

The government’s core development philosophy dictates how the government may control and regulate. The incoming government must decide how control will be maintained across sectors, which sectors can be left to the market, and how much control should be retained to maintain an appropriate balance. Rather than making a checklist of random policies, if the policies are guided by a specific development philosophy, a more consistent political infrastructure may support the effective implementation of policies.

Moshahida Sultana is an Associate Professor in the Department of Accounting at Dhaka University. She can be reached at moshahida@du.ac.bd