Dreams on canvas: the silent worlds of neglected children

Paintings often open doors to worlds we forget how to enter. As adults, our imaginations become layered with pretence and caution, but children create from a place unfiltered and intensely real. Their drawings are the reflections of what they see, fear, love, and hope for. Nowhere was this truth clearer than at "The Catcher in the Rye", a two-day exhibition held on December 5–6 at Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, showcasing the artworks of children born and raised in the country's red-light areas. It was organised by Project Pothchola, an initiative of the Give Bangladesh Foundation.

The title draws from J D Salinger's novel, where Holden Caulfield imagines himself as a guardian protecting children from losing their innocence. Similarly, this exhibition becomes a space where the children's art preserves that innocence and asserts their right to dream.

The opening ceremony began at 3:30 pm with chief guest cartoonist Ahsan Habib. "Children don't pretend. They draw what they truly feel. Their paintings are honest, almost like looking directly into their eyes," he shared. The ceremony began with a heartfelt group performance of "Amra Korbo Joy," sung by the children themselves—an earnest, hopeful chorus that set the tone for what followed.

The artworks were created by two groups: children from the Astha shelter home and children living in the Daulatdia brothel area. Their pieces were thoughtfully arranged in segments, allowing visitors to move through the different corners of their worlds. There were paintings, installations, photographs, videos, and handmade crafts.

One section displayed photographs of Daulatdia, alongside black-and-white blurred portraits of the children—an artistic way that preserved their dignity while making the starkness of their surroundings unmistakable. Narrow alleys, dim rooms, and minimal study materials told stories of constraint, but never of defeat.

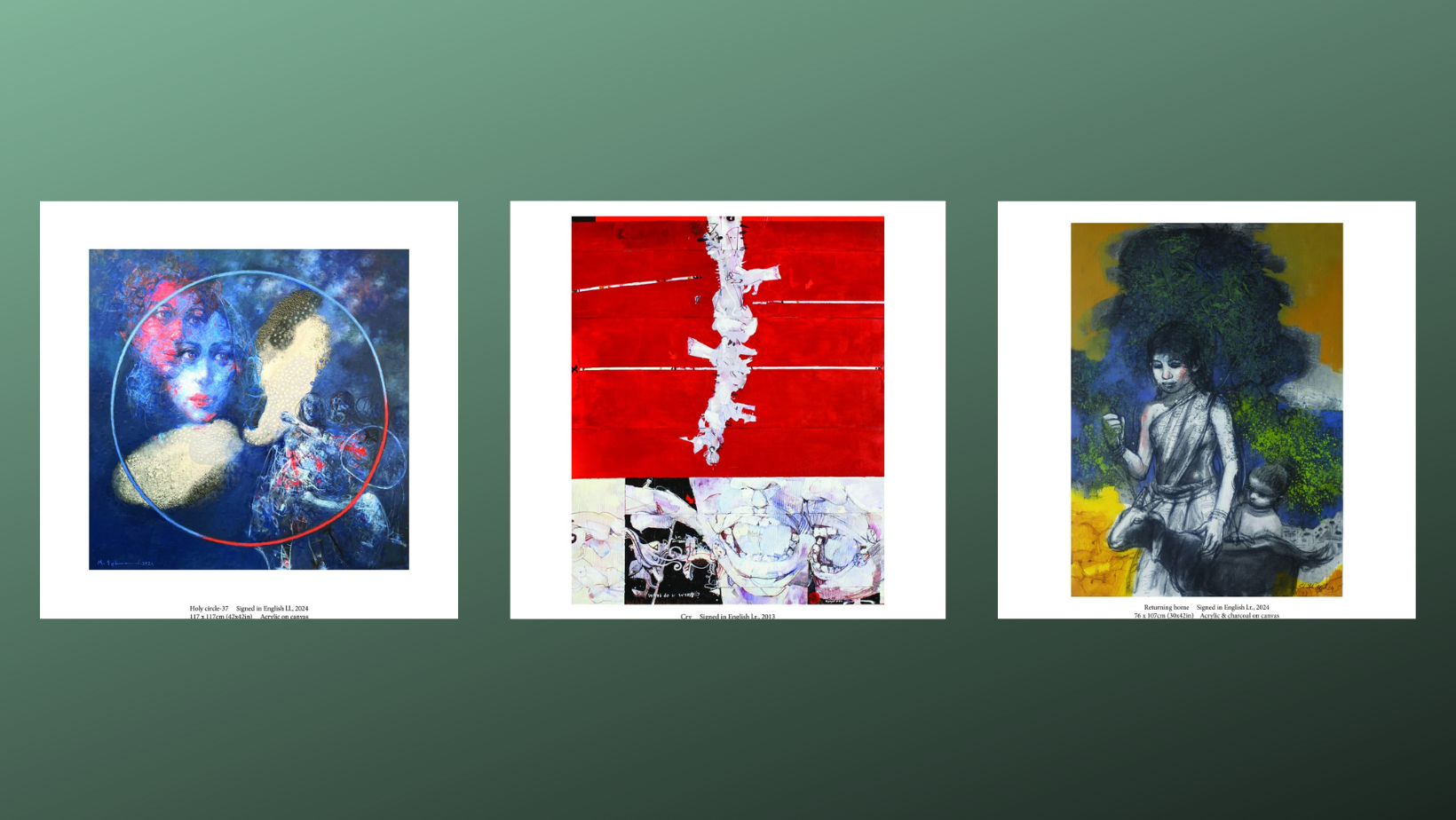

The paintings themselves ranged from whimsical to haunting. Some children covered their canvases in bright blues and balloon-filled skies, like the piece titled "Up, Up and Away" showed a blue sky filled with colorful hot air balloons decorated with buttons. There were abstract paintings using the colors they imagined. Interestingly, many children chose darker colors despite having access to the full palette. The organisers noted this choice was entirely theirs—brown, dark red, dark blue appeared frequently. Some paintings featured dark colors even in skies and trees, in natural scenes where one might expect brighter tones.

Psychologically, children who've experienced difficult circumstances sometimes use color as their first language for emotions they cannot yet verbalise. Dark colors don't necessarily indicate sadness alone, they can represent a need for boundaries, for contained spaces, for control in lives that have felt chaotic. The choice reveals how these children process their world.

Many paintings depicted natural scenarios. One young artist explained, "I have painted my dream house in a natural scenario." Houses, flowers, and nature dominated their canvases. Under the theme "Home of Happy Colors," paintings showed dream homes where every color of their imagination exists.

Some artworks captured deeper longings: a child painted himself looking through a window, watching a future version of himself performing on a stage—a quiet dream of becoming a musician. In a segment called "Amar Priyo Bondhura" (My Dear Friends), children painted pictures with their friends. One painting portrayed loneliness—a child alone, the entire composition conveying solitude. Another showed a child who has to work but dreams of going to school, capturing the daily reality these children face.

In another corner, abstract pieces made with fingers and thumbs showed the children's joy in uninhibited creation. Their handmade clay foods were just as revealing: miniature chickens, eggs, curd, bread, and bowls of rice. These reflected not only what they usually eat, but what they wish they could eat, portraying five meals a day, full and satisfying. Through these tiny sculptures, hunger transformed into imagination, and imagination into art.

The installation paintings included birds made with stones, gardens created with fingerprints, birds and butterflies, and fish in the deep sea. There was a 3D dream house model featuring a beautiful house, a school, a colorful garden, a playground, a small pond, a canvas on the rooftop, and two cats, reflecting a complete world imagined by the children.

Nearby stood the "Tree of Letters," its branches covered in handwritten notes from the children. Some expressed simple desires, others carried big dreams. One child wrote that she wants a room where she can dance, sing, and play music on a speaker—and a place to keep her sarees because she loves wearing them. Each letter reads like a quiet confession from hearts that rarely get asked what they want.

The exhibition ran from 3 pm to 10 pm on both days at Gallery 5 of the National Art Gallery, inviting visitors from all backgrounds to witness what these children see when they imagine home. Ashik Chowdhury, Executive Chairman of BIDA and BEZA, visited the exhibition with his family. He told The Daily Star, "It's very different from other exhibitions. We work for a lot of communities but we do not cover this community. It's very touching to see that someone's trying to save the kids and their dreams."

In a video screening, the children spoke about their aspirations to become teachers, doctors, army officers. They dream of travelling the world using Doraemon's "Anywhere Door", building nice homes, and living lives free of fear. Ahmed Fahmi, Executive Director of Give Bangladesh Foundation, shared, "Children born in the red-light community remain absent from the very systems designed to protect them. This exhibition is a reminder that recognition is the first step toward reform. These artworks offer evidence of the potential that Bangladesh cannot afford to overlook."

"The Catcher in the Rye" was not just an exhibition, it was an invitation to witness childhood in its most honest form. Through colors, textures, and tiny handmade dreams, these children showed not only who they are, but who they hope to become. Their art asked visitors to pause, to feel, and to remember that behind every stroke lies a child trying to hold on to imagination, even while walking through the shadows of reality.

It was a reminder that innocence, once recognised, deserves not protection alone but opportunity, dignity, and a world willing to let it grow.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments