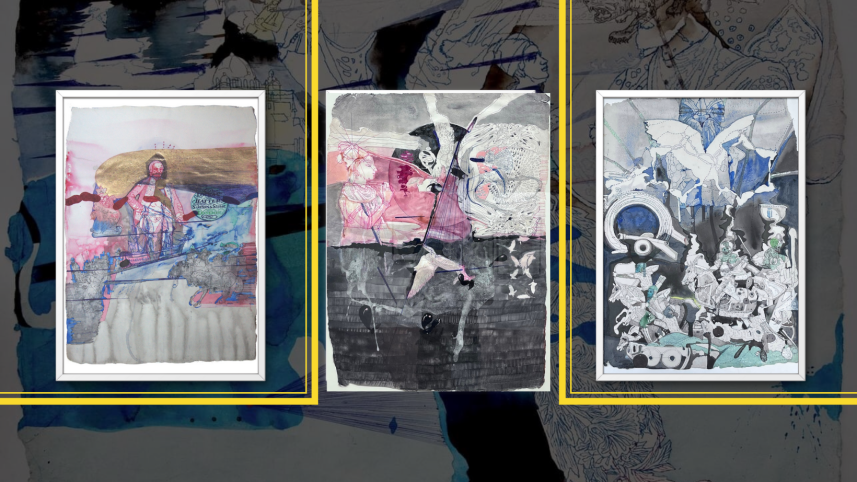

Mapping Bengal’s inherited histories through art and memory in Firoz Mahmud’s work

In this series of mixed media on paper on his own native histories and legacies, Firoz Mahmud draws on the histories of his home in the Bengal region, where many communities and their cultural sites, agriculture, and industries have been transformed by constant colonisations over nearly 2,000 years. Although the rulers of the region legendarily staved off an attack by Alexander the Great in 325 BCE with a cavalcade of elephants, the people and fertile land of the greater Bengal region — spanning present-day Bangladesh and India — have endured continuous waves of military invasion and civil war, including the Islamic conquest led by the Ghurid general Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, the Mughal annexation during the reign of Emperor Babur, the defeat of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah by the British East India Company, and later, large-scale intercontinental migrations following the Partition of Bengal along the Radcliffe Line and the subsequent Bangladesh Liberation War.

Tracing the paths of these complex histories rooted in the violence of occupation, Mahmud illuminates their continuum to present-day Bengali immigrant communities in New York City, where he now also resides. Mahmud has enjoyed reading history and geography since childhood, inspired by his father and grandfather, both academic historians and teachers. Combining a wide range of media, he links disparate times, places, and perspectives through diagrammatic drawings and paintings that chart the socio-political impact of successive regimes and the Bengali diaspora. Alongside mixing media, Mahmud weaves together culturally established and personally invented iconographies, incorporating images culled from historical photographs into multilayered palimpsests.

For example, the most pronounced component of "On-Sight" (Luxury) is a large, ornately bordered portrait floating in the upper left of the picture plane, high above the fray of ordinariness. Vivid red rays emanating downward from this majestic ellipse towards the faceless crowd below emphasise the subject's undeniable power. Whether the elevated figure is a ruler or conqueror surveying a newly claimed land, the indistinguishable people on the ground initially appear to await benediction rather than resist subordination. Yet the organic black marks shrouding the masses may conceal their true selves from interrogation and subjugation. For the artist, the smoky wisps leaving their bodies signify not only the spiritual and psychological drain of colonisation on individuals forced to surrender their labour, but also the extraction of economic resources by successive authoritarian powers in the Bengal region.

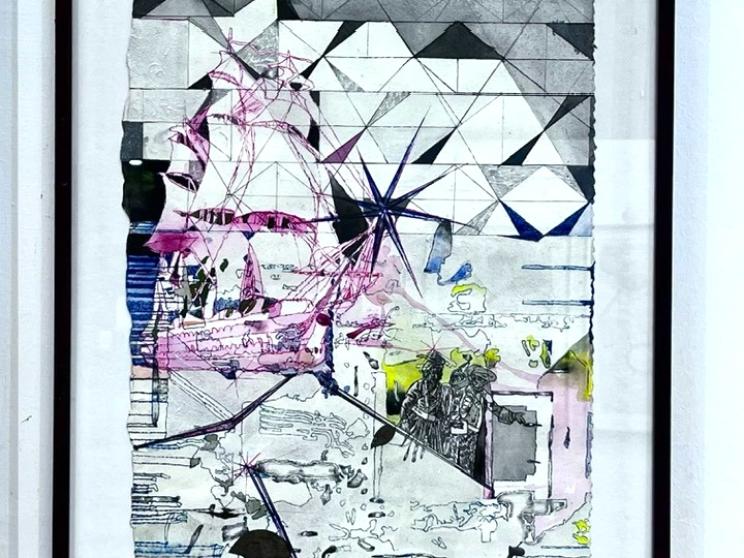

In the lower left, where a flock of people occupies a marketplace, Mahmud employs a single vanishing point to construct the architectural scene before disrupting the logic of linear perspective by juxtaposing disproportionate elements and layering interfering lines. This fracture, one of many within the work, unsettles both image and narrative, leaving viewers to question whether something essential lies beyond the frame. On the right, Mahmud retraces the same vessel three times using contour lines, inviting renewed observation with each repetition. Whether the object has been preserved across generations or destroyed and remade, generational trauma is inscribed within this triplicate form.

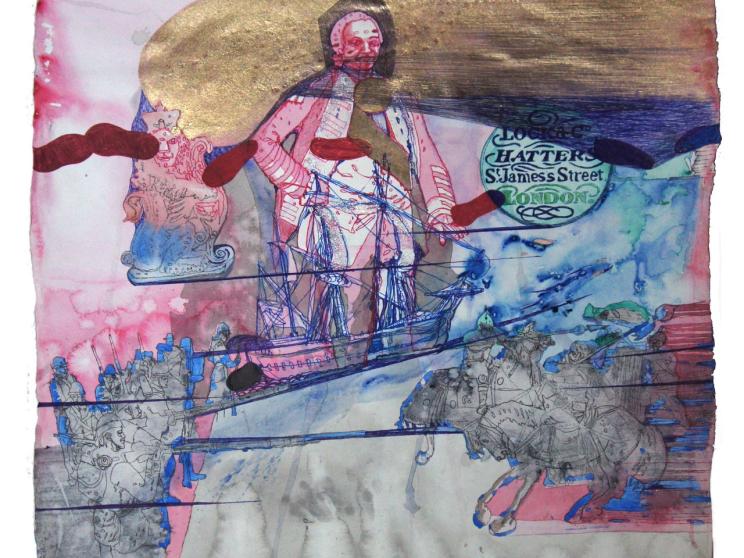

While producing the "Drawing Reverberation" series, Mahmud worked simultaneously on multiple sheets of homemade paper laid across the floor, repeating motifs, colours, and textures. Owls appear to symbolise wisdom, tigers power, and eyeglasses a vision of hope and desire. In "Entanglement" (Digitised Pseudohistory), soldiers and three-masted schooners recur as symbols of war and economic exploitation. The upper third is dominated by a sailing vessel used for military transport and colonial export. Though steady in form, its shadow appears unmoored, while dark ink pooling behind it suggests impending disaster.

Below the sea's surface, Mahmud reconfigures his recurring ray motif, converging blue ballpoint lines at a single point to convey the interconnected fate of military actors. The Mughal Nawabs' continuum is reinforced through near-symmetry, with mirrored figures facing one another. Their visages are obscured by washes of miniature cavaliers, underscoring the erasure wrought by centuries of conquest. Even the conquerors, Mahmud suggests, ultimately return to dust.

In "Shawopno" (Satt Somudro Tero Nodi Pari, Pseudohistory), Mahmud shifts focus from invaders and faceless masses to individual Bengali migrants, each framed in decorative borders once reserved for rulers. Saturated in yellow and extending edge to edge, the work reimagines ships as vessels carrying people rather than goods — or as sites of departure from the port of Calcutta — marking a further depletion of the region's human capital.

In "The Syncretic Preach", Mahmud adopts a pared-down approach, limiting both media and surface area to produce graphic character and scene studies. Here, Islamic geometric patterns and architecture are repositioned within the compositions. A mythological hybrid emerges as the Sixty Dome Mosque is mounted atop the legs of a cavalry horse, visualising the arrival of Islam and its visual traditions in Bengal. In a triptych from the same series, fragments of Islamic geometry overlay images of a herald bearing a mosque maquette, reiterating the religious and architectural transformations of the region. As the artist notes, "The series of works are about how Islamism prevailed in South Asia and how Turkic and Arabians preached Islam in the region."

Alongside works on paper, "Inscaping Legacies" includes large-scale Lapaya oil paintings on reshaped, asymmetrical canvases. In "On-Sight" (Cause of Gain-1-b/b/w), Mahmud reworks the formal portrait of a decorated warrior, replacing the head with shifting symbols — a gathered court, a dinosaur skeleton pierced by a sword — documenting the erosion of military authority rather than its triumph.

Mahmud emerges as a compelling chronicler of inherited histories. As suggested by the title "Inscaping Legacies", these events continue to shape both place and psyche. His works function less as seamless collages than as urgent thought maps, drawn by an inheritor determined to preserve memory against erasure. In continuing the historical work of his father and grandfather, Mahmud sustains a three-generation lineage of story-keeping, securing histories that might otherwise fade or be overwritten.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments