Fail to save rivers, and we fail to save ourselves

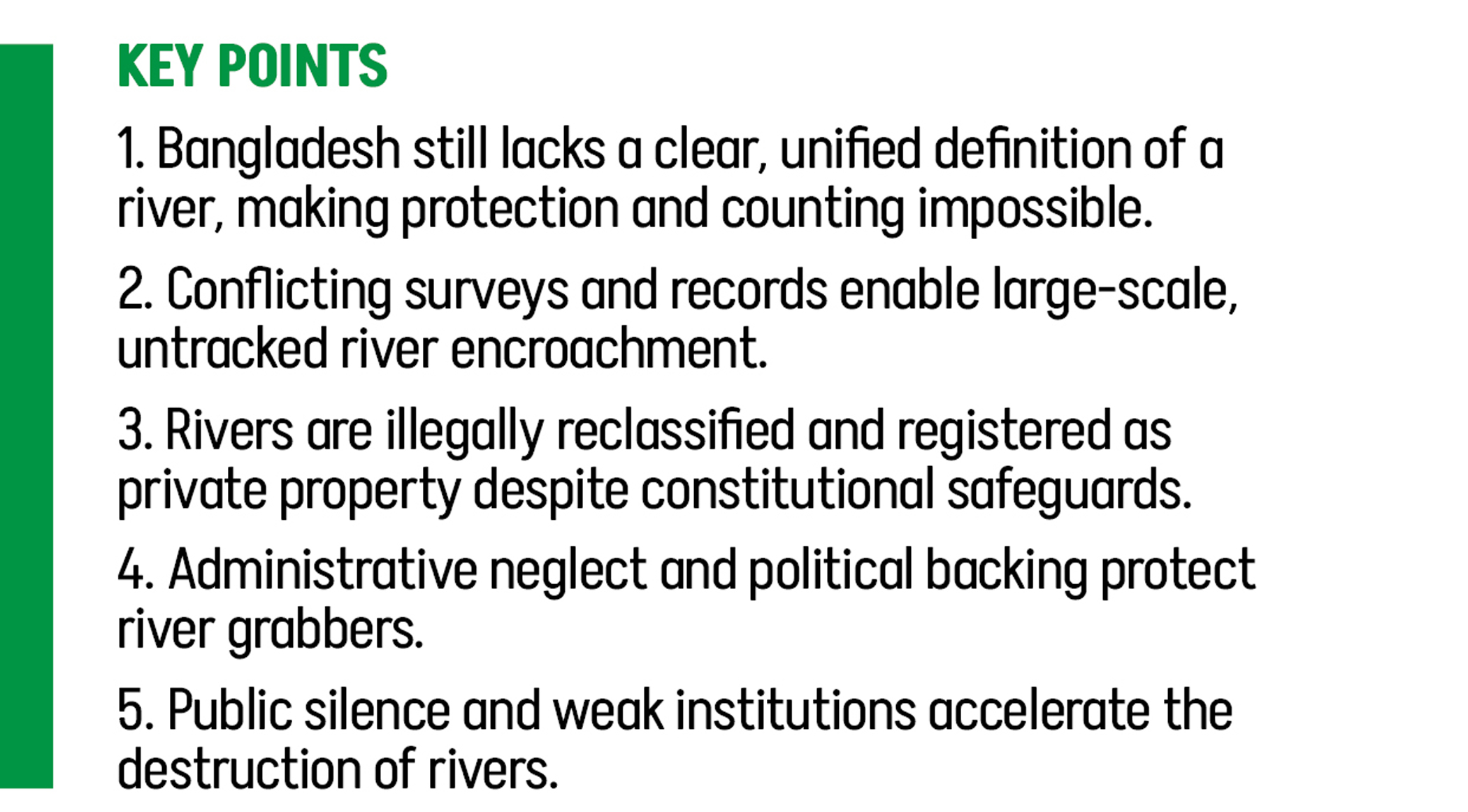

Our country is a riverine land. Rivers are deeply intertwined with the very formation of this land. Yet, even today, the definition of a river has not been finalised in Bangladesh. Without a settled definition, it is impossible to determine the actual number of rivers. In 2023, the National River Conservation Commission proposed a definition of a river. However, it does not appear that all government agencies have accepted this definition. Had it been accepted, the same definition would have been followed in determining the number of rivers.

Does only what was marked as a river in the British-era CS (Cadastral Survey) maps qualify as a river? Are flows that local people have, for generations, called rivers not rivers at all? Unless it is clearly defined which flow can be called a river, it will never be possible to calculate their number. And without knowing the number of rivers, it is also impossible to say how much river area has fallen into the hands of illegal grabbers.

To our knowledge, during the British cadastral surveys there were no clear guidelines on which flow would be considered a river. Many wide and long flows were recorded as khals (canals), while comparatively narrow and short flows were recorded as rivers. It appears that surveyors simply recorded flows according to the names used locally: what people called a khal was recorded as a khal; what they called a dara was recorded as a dara; similarly khari, dohor, or chhara were recorded as such. As a result, many sections within rivers, canals, daras, chharas, dohors, and kharis were recorded as wetlands or waterbodies.

Officially prepared lists of rivers in Bangladesh have changed year after year. Many of us who have worked on river issues for a long time believe that Bangladesh has more than two thousand rivers. In 2005, the Bangladesh Water Development Board spoke of 230 rivers. In 2011, the same institution reported 405 rivers. In 2024, the National River Conservation Commission stated that there are 1,008 rivers. In 2025, the Ministry of Water Resources of the interim government published a list identifying 1,415 rivers. This list was prepared within a very short period of time by the interim government.

Across the country, we are witnessing countless rivers being encroached upon. The scale of this encroachment is not publicly available. To my knowledge, the government has still not undertaken work on encroached river land using CS maps. The main reason for this is a lack of political will. Without identifying encroachment, it is impossible to free rivers from illegal occupation. A few years ago, when Dr Mujibur Rahman Howlader was Chairman of the National River Conservation Commission, we learned of more than fifty thousand encroachers across the country. The government procrastinated in evicting them, and as a result, the illegal occupations remained.

Many rivers have even been recorded in the names of private individuals. I would like to mention one or two such examples. In Nageshwari upazila of Kurigram district, there is a river called Girai. It is recorded as a river in the CS records. However, in the RS records, the river has been registered in the name of a private individual. Some rivers have been completely occupied; others are gasping for breath under encroachment; and in many rivers, encroachment has only just begun. Apart from the rivers of the Sundarbans and the hill tracts, it is doubtful whether a single river in this country remains entirely free from illegal occupation.

Neglect by those responsible for river protection, combined with public indifference, is allowing our rivers to be illegally occupied. No action is taken against river grabbers, or against those who unlawfully register rivers in private names or facilitate such occupation. There is virtually no accountability for officials responsible for rivers.

The primary responsibility for river protection lies with Deputy Commissioners (DCs), Upazila Nirbahi Officers (UNOs), and Assistant Commissioners (Land). However, DCs and UNOs do not treat rivers as a priority issue within their jurisdictions. Moreover, since society at large does not strongly protest river encroachment, many officials choose to ignore the issue and complete their tenure without confronting it. Because politically powerful figures often support river grabbers, DCs are reluctant to take action against them.

River land is often registered in private names, land revenue (khajna) is assessed and collected, and official records are prepared. At the root of every such process lies the illegal reclassification of river land. Legally, there is no scope to change the classification of river land. Constitutionally and legally, rivers are public property. As rivers are public property, the government has no authority to allocate them for private use.

Since river property cannot legally be reclassified, any arrangement to sell it is entirely unlawful. Once the classification of river land is illegally altered, the path is cleared for encroachers. Illegal occupiers then register river land in their own names under other land categories. When the issue of land revenue arises, government officials, often in collusion, accept khajna.

If a river is registered in a private name, it is unquestionably illegal. Yet even when such illegality becomes public, people do not protest. This protest, however, is crucial. When someone fills a river with earth or creates ponds within a river, local residents must be the first to raise their voices. While working directly on river issues, I have seen countless structures inside river channels. It is obvious to the naked eye that these structures lie within the river. In some cases, roads have even been built by blocking the natural flow of rivers. Yet local people have not objected. This lack of resistance accelerates river encroachment.

Often, river encroachment begins in the name of religious institutions or public welfare clubs. Later, private encroachment spreads around these structures. In many cases, bridges are constructed narrower than the river’s actual width. Over time, the width of the bridge is treated as the river’s width, and encroachment continues accordingly.

There are also difficulties associated with river protection movements. Those who advocate for river conservation are often labelled as anti-government. Through this, local administrations are positioned against activists. We had hoped that realities would change after the July uprising, but that expectation now seems naïve. Instead, encroachers have become even more powerful. If future elected governments do not give special attention to river protection, it will be extremely difficult to save our rivers.

If the government truly wishes, every river in this country can be freed from illegal occupation. Rivers can be protected within the existing administrative framework. However, for long-term protection, the National River Conservation Commission must be strengthened. The Commission should have regional offices in every division, along with special powers to evict illegal occupiers. Accountability of Commission officials must also be ensured.

Public awareness is essential. Exemplary punishment must be ensured for river encroachers and everyone involved in the encroachment process. Only through a combined effort of legal enforcement and public awareness can the rivers of our country survive. There is no alternative to freeing our rivers from encroachment for the greater interest of future generations.

Tuhin Wadud is the Director of Riverine People and a Professor in the Department of Bengali at Begum Rokeya University, Rangpur. The article has been translated into English by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.