Sharpened focus, unshaken resolve: Women breaking barriers in sports

For decades, girls in Bangladesh have grown up hearing an invisible rulebook: real sports, the ones defined by sweat, muscle, adrenaline, and grit, are spaces for boys. Boys played in the playgrounds. And girls? They used to stay at the margins. However, that scene is beginning to change.

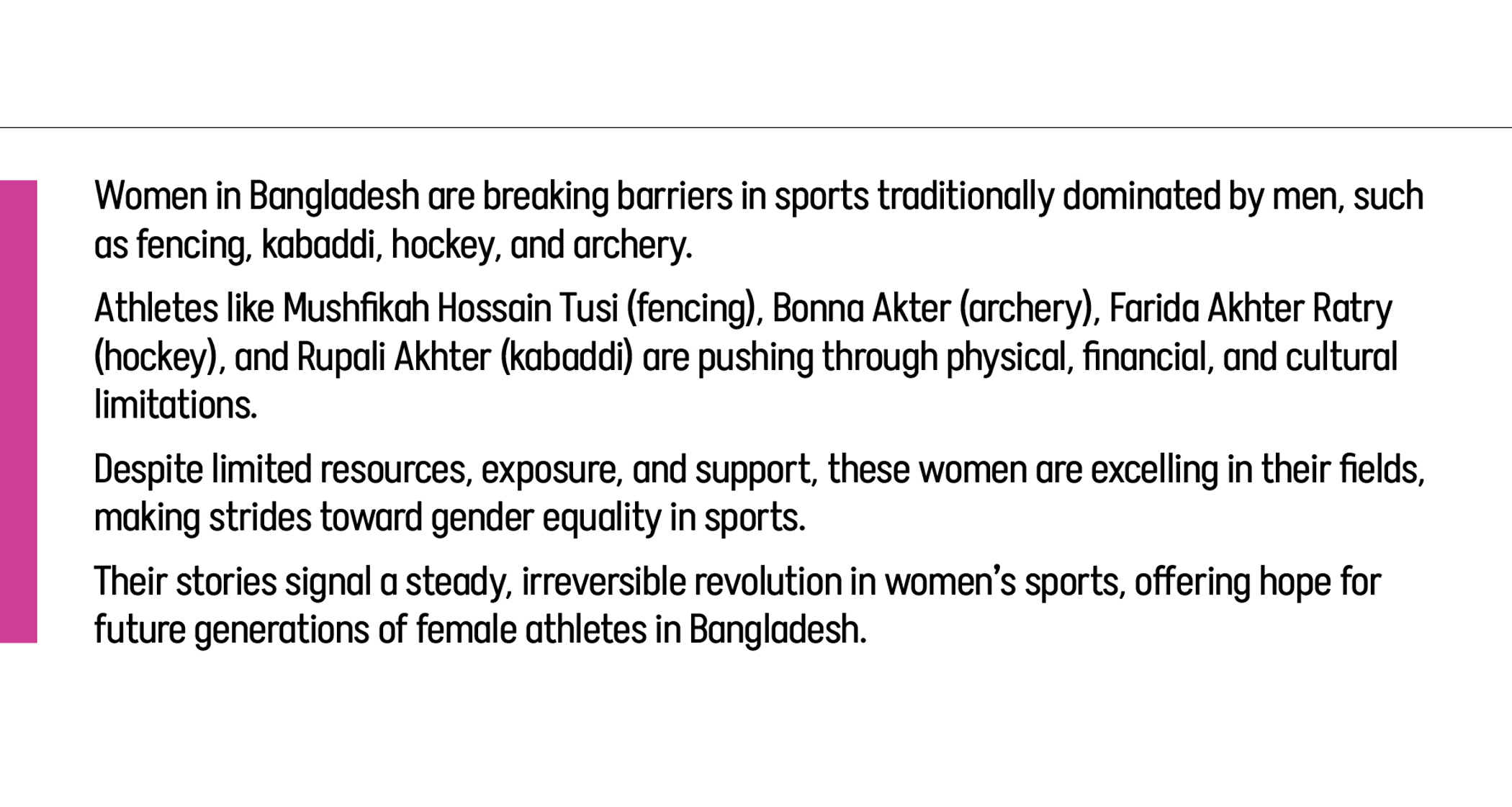

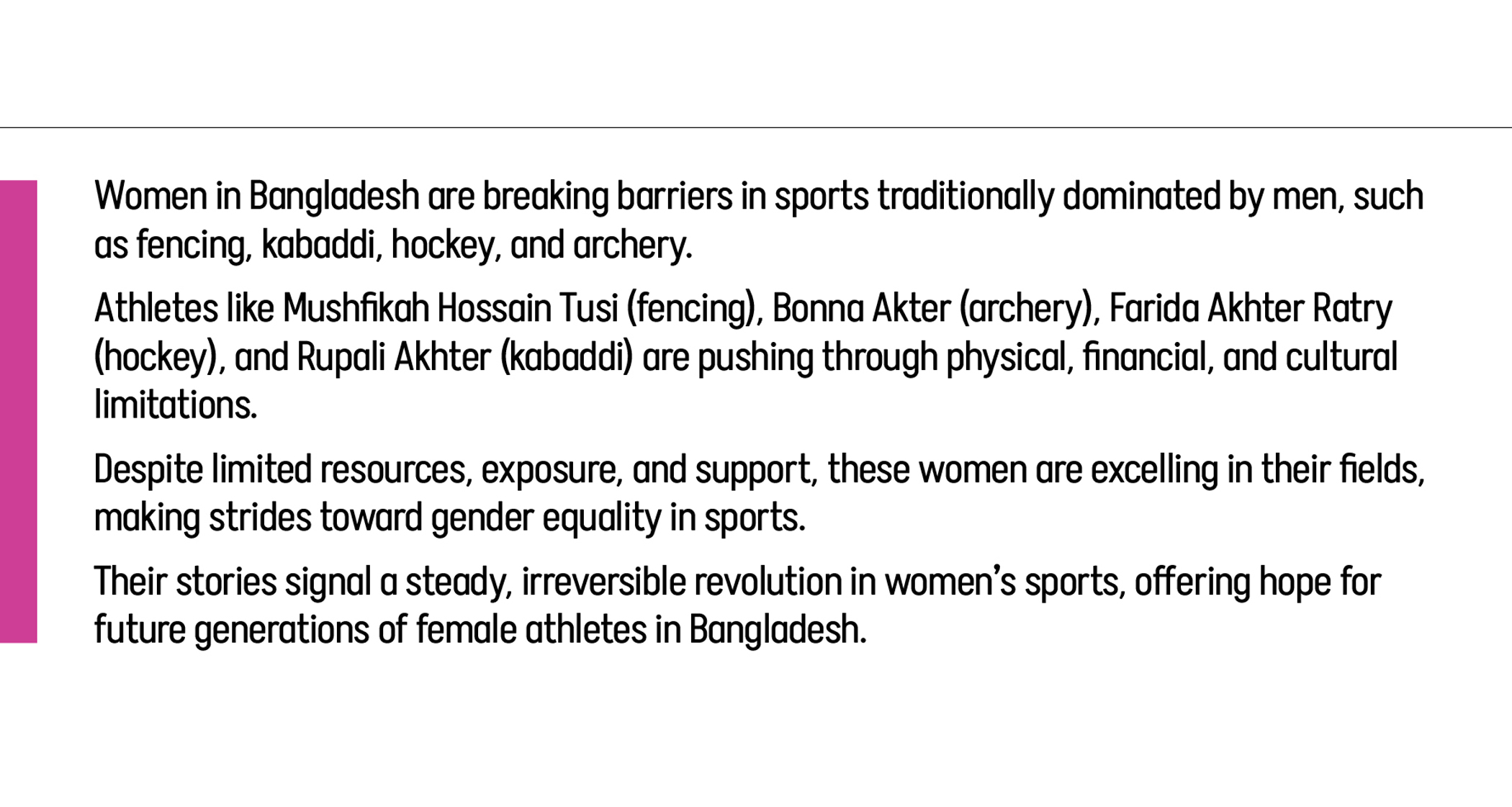

Across the country, female athletes are beginning to enter arenas that once seemed sealed off from them: fencing halls, kabaddi courts, hockey turfs, and archery ranges. Long considered somewhat unconventional for women, these sports have become the unlikely sites for reinvention. And in that shift lies a larger transformation in Bangladesh’s sporting culture.

Grace under pressure, courage in motion

“I saw the footwork, and it felt elegant. I’m drawn to elegant things,” says Mushfikah Hossain Tusi, laughing a little. So far, Tusi has participated in four national tournaments, a commendable achievement in a country where fencing was barely part of the public consciousness even a couple of years ago.

One cannot say fencing in Bangladesh is a sport that was inherited from tradition or even built into school culture. Yet, inside Dhaka’s sports complexes and private clubs, promising fencers like Tusi are learning how to move with a blade in hand with dexterity.

At Navy College, where Tusi studied, she would see the Navy fencing team training early in the morning.

“I felt inspired by watching them practise in our sports complex, and I thought, why can’t I do this too?” she recalls. This is how she joined the Royal Fencing Center. Nevertheless, she gradually discovered that fencing, the sport she considered so elegant, comes with weight, sweat, and hours of discipline.

“You need an immense amount of mental labour, along with physical endurance. It is not easy, as during training, your mind has to be right there, and this is what I love most about this sport. It keeps you focused,” she explains.

The sport does not allow an athlete to blend into a team or disappear in a crowd, unlike other team sports. Rather, it forces you to stand alone, masked, wired, and watched. In a country like Bangladesh, where girls are often told to shrink themselves, fencing’s insistence on visibility can be a radical experience.

“Discrimination is present everywhere, including sports, but I have never faced this. In fact, everyone — our seniors, the federation, my coaches — encouraged me. They are always like: ‘Yes, you can do this!’ This encouragement matters to me the most,” Tusi shares.

Yet, numerous times, Tusi has faced this question: Why fencing? — including from her own family. “My father and mother asked why I was doing this,” she admits. “But when they saw how healthy I had become, they stopped questioning.”

For a young woman who is standing firmly on a piste, blade in hand, mask on, and body steady, fencing is certainly a steady assertion that she has the right to take up space and compete. And perhaps that is why more girls will follow, because female athletes like Tusi are making it more visible with time.

Precision, patience, and a national stage

Amid persisting constraints, young female archers are advancing to significant stages and earning attention for more than just participation. Take, for example, the 2025 Asian Archery Championships in Dhaka, where Bonna Akter and Himu Bachhar advanced to the final, defeating strong teams from countries such as Bhutan and South Korea.

Nevertheless, the journey to international tournaments has been anything but easy, as Akter details, “Back in 2014, I went from Faridpur to attend the Bangladesh Ansar trials and started practising archery. At first, I used bamboo bows. Although they allowed me to learn the basics, I knew I couldn’t go far using them. Ultimately, I managed to acquire a compound bow.”

That was a turning point for her, and within a year, she rose to the national team.

At its core, archery is a game of mental discipline. And despite being considered somewhat of an unconventional sport, in recent years, it has become one of the fastest-rising sports for Bangladeshi women. It is not because archery is something that is traditionally encouraged, especially to girls, but because it offers a level playing field where gender does not automatically decide ability.

Akter elaborates, “The calmer I keep my mind, the better my game gets. Years of training have conditioned me, and from the moment I shoot my first arrow, my mind starts to focus on practice. I rarely notice what is happening around me.”

But the mental quiet she nurtures on the field is disrupted when she thinks of the sport’s place in the country. “Football and cricket get so much publicity. We don’t,” she says. “If archery got that focus and if the media helped more, the government would notice too.”

For Akter, archery is her only source of income now. Her rigorous routine is what keeps her motivated in spite of the meagre honorarium she receives. “I stopped my education because I was so engrossed in sports,” she says. She doesn’t regret it, but the system around her hasn’t risen to match her commitment.

Running hard without a clear path ahead

Farida Akhter Ratry, centre midfielder of the Bangladesh women’s hockey team, began playing hockey as most girls discover a certain sport: by accident. “It was during an inter-school tournament in 2016, when I first played hockey. I was a student in Kishoreganj, and in my school, boys practised hockey regularly.”

Ratry was inspired by her district coach and brother. And soon, she started her training on the Sylhet fields, anticipating opportunities that rarely came.

When asked about her biggest frustration, she answered, “It is not lack of talent, but rather the lack of games and exposure. We are training regularly and are more than willing to play. But there are barely any tournaments for us. Many of our seniors have dropped out, gotten married, or quit because there’s no chance to play.”

Rupali Akhter, kabaddi

She has represented Bangladesh twice internationally, once as a junior and once as a senior. But the five-year gap since her last international match hangs over her career.

Despite the recent success at the AHF Women’s Under-18 Asia Cup, where the Bangladesh women’s hockey team earned the bronze medal in their maiden appearance, the women’s national field hockey team still has far to go.

Ratry suggests, “Every year we need at least one or two domestic tournaments. Along with that, of course, the chance to play regular international tournaments, and then maybe we could bring laurels for the country.”

Strength in a sport that barely pays

Kabaddi demands physical contact, strength and audacity, qualities that girls are seldom encouraged to display. However, Rupali Akhter, the captain of the Bangladesh women’s kabaddi team, was adamant about defying the norms from the start.

“I was involved in athletics in school, 100 and 200 metres. A coach noticed me and suggested I should give this a shot. I eventually reached the Women’s Complex, where I was selected for the national team in 2009.”

Her career since then has been full of international matches — World Cups, Asian Games, and regional tournaments. But the rewards do not match the effort. “For international camps, we get Tk 10,500 as pocket money,” she says. “Other than that, no salary.”

Despite the limitations, Akhter doesn’t want to leave kabaddi behind, but rather, wants to contribute so that this sport can flourish. “If I retire from the national team, I’ll move into coaching.”

Her decision captures the state of kabaddi perfectly. There is passion, talent, and persistence, but an almost complete absence of infrastructure.

The larger picture: A country in transition

Even though these four athletes are from four very different sports, their stories are almost the same. Whether that’s fencing, kabaddi, hockey or archery, female athletes are doing incredibly well in their respective fields. However, the limitations they face are not vague in any manner – financial ceilings, lack of tournaments, inadequate training facilities, and a cultural hesitation that still lingers.

But what’s new is the wave of girls who are stepping in anyway.

Their stories give testimony to one fact: the revolution in women’s sports in Bangladesh is steady and irreversible.

Photo: Silvia Mahjabin/Courtesy

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments