Jamdani and Nakshi Kantha enter global conversations through design

At first glance, you may feel like looking at a thrifted jacket or a misfit patchwork dress. Once you look closely, you will see the stitches do not repeat. Instead, the embroidery breaks the pattern. Although the threads are uneven and frayed, they all hold together. This is Nakshi Kantha, but reimagined! On the other end of the spectrum, you might find a crisp, translucent kurta made of fabric so light it almost blends into the air. If the motifs look like tiny flowers or water droplets, you are most probably looking at Jamdani, worn as an everyday casual outfit.

These are not merely nostalgic revivals, but active reinterpretations of Bangladesh’s textile heritage. They are not only making their way into contemporary wardrobes but also global conversations.

A past that refuses to stay in the past

Traditionally, a form of hand-embroidered quilt made from old sarees and sometimes lungis, Nakshi Kantha was once a quiet craft mindfully employed by rural women. The art of kantha stitching was and is still deeply personal — embellished with birds, vines, boats, and scenes of everyday life.

Samaha Subah, founder of the experimental label SIZ, is bringing the kantha out of the homes and into the wardrobes and for her, Nakshi Kantha functions as a canvas.

“For me, it’s like painting. Through this craft, you can explore your own imagination. You can choose what you want to illustrate – florals, patterns, or even something like a dragon,” she says.

For generations, Nakshi Kantha has been a domestic, traditional textile, stitched from old clothes, made into a quilt, and embroidered with intricate motifs. However, today, the same stitchwork is being translated into streetwear, handbags, and even jackets. And it is being done by none other than our very own Bangladeshi designers like Samaha Subah.

In slight contrast, Jamdani, woven in and around Dhaka for centuries, has become internationally prized. The weaving of Jamdani is a very laborious job, with supplementary threads added by hand to create motifs that float within the cloth. And for a long time, it has been considered too exquisite for everyday use.

This, however, is no longer the case.

Presently, many young and conscious designers are attempting to redesign it, not for the sake of modernisation but to make it in vogue again. One of them is Farhana Munmun, founder of Bene Bou. Growing up in Demra, the heartland of Jamdani weaving, she remembers looms as a phenomenon that was a part of everyday life.

“While I was working, my colleagues would ask me to bring Jamdanis for them. That’s how it started,” she recalls. At first, Munmun worked only with sarees, sourcing directly from weavers she met by visiting haats at dawn. She soon realised that Jamdani’s biggest obstacle was not design, but wearability.

Her customers abroad could not wear sarees in cold climates. Many wanted Jamdani clothing that was washable and practical. This is how she started to diversify, and now, Munmun is designing jackets, coatees, kurtis and long vests.

She argues, “If we want to save Jamdani, we must diversify it. People should be able to wear it in their everyday lives.”

Due to rapid industrialisation, both crafts are facing decline and mostly remain reserved for festivities. Therefore, reinvention has become a necessity, as it addresses an urgent question: how to survive in a world that has a faster consumption rate and cheaper alternatives.

Reworking the loom

For decades, Nakshi Kantha and Jamdani have been labelled as “heritage,” a word that often traps these textiles in museum-like reverence. It is high time they should be pulled firmly back into the present by being reconfigured as contemporary fashion, lifestyle objects, and cultural statements.

Subah is capturing this reconfiguration boldly. Her latest collection features a dragon motif, stitched entirely by hand, that crawls across the back of a jacket — a design familiar yet unexpected and unmistakably contemporary.

“I feel fascinated by Nakshi Kantha’s adaptability, you know, not just stylistically but structurally. I like to intentionally keep my designs mismatched because I want my pieces to look like the fabric had been cut directly from old kanthas,” she explains.

Subah wants to challenge the mass-market expectation of perfect symmetry. This is why one may find variation in thread tension or the small shifts in motif placement in her collection. This, she explains, is not a flaw, but the signature of authenticity.

“You see, the pieces in my collection are not made by machines. Real artisans make them, so naturally, there will be certain differences. And that’s the beauty of it, which I am very proud of,” she remarks.

While Nakshi Kantha is being translated through stitch, Munmun is trying to reinterpret Jamdani through structure. “My clients used to complain: ‘Jamdani frays, Jamdani can’t be washed. If only there was something more practical!’ And so, I switched looms and experimented,” she shares.

In an attempt to get a more practical output, Munmun worked with slightly thicker thread counts – still handwoven and rooted in tradition, but washable and more durable. And then she broke the rule and moved Jamdani beyond the saree.

Today, her collections are being sought after by Bangladeshi and international customers alike. And perhaps most remarkably, Munmun’s most impactful contribution is in upcycling.

She explains, “I collect worn-out Jamdani sarees that people would otherwise throw away. The parts where motifs are intact, I turn them into wall frames, jewellery, hairbands, even shoes.”

In her hands, Jamdani has now become a resource, turning into a memory bank with infinite second lives.

Both of the designers are aware of these textiles’ luxury appeal. However, they are determined not to treat them as something untouchable but as a wearable statement; something that belongs in offices, universities, and social gatherings. In this way, both Jamdani and Nakshi Kantha are not being diluted, but they are being redistributed across the aesthetic spectrum.

Can these crafts reach the world?

The answer is yes, but not passively.

Munmun shares details about how foreigners keep returning to her stall at embassy fairs. “I have had clients who came back two or three times. They find the motifs and other small details very attractive, and this is why they keep recommending Jamdani to others.”

She has been selected for an SME Foundation–supported fair in the UK, pending visa confirmation. For her, the one thing missing is not demand but proper infrastructure.

“Now, more than ever, we need a structured channel,” she says plainly. “Buyer‑seller meetings, international fairs, platforms where we know whom to approach and what global markets need.”

According to her, without systematic export channels, artisans, especially those living in remote areas, will stay trapped in domestic volatility. Simply put, without cultural positioning, Jamdani and Nakshi Kantha will remain beautiful heritage products, but can never be globally competitive.

Both Subah and Munmun are clear about one fact: the path forward demands a thoughtful collaboration between local designers, weavers, and international platforms.

Nevertheless, on the brighter side, both Jamdani and Nakshi Kantha are transitioning from household objects and ceremonial gifts to evolving design languages that can move fluidly between climates and generations. And this reminds us that heritage survives when it learns to speak the language of the present.

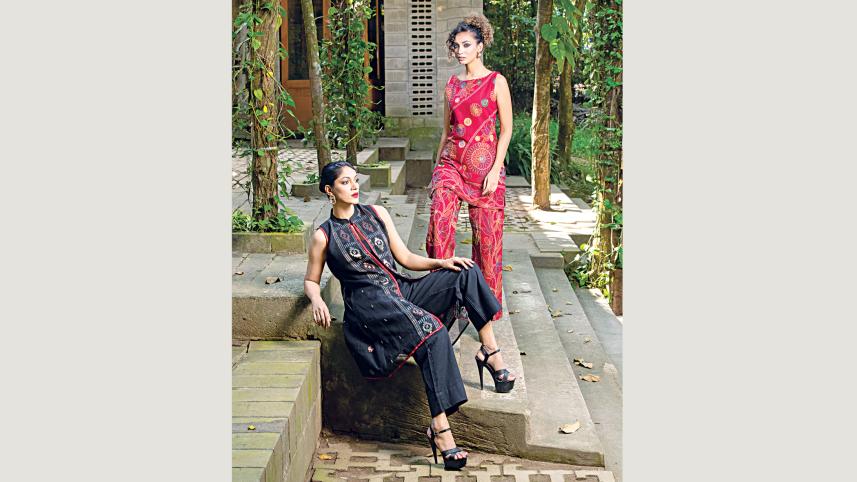

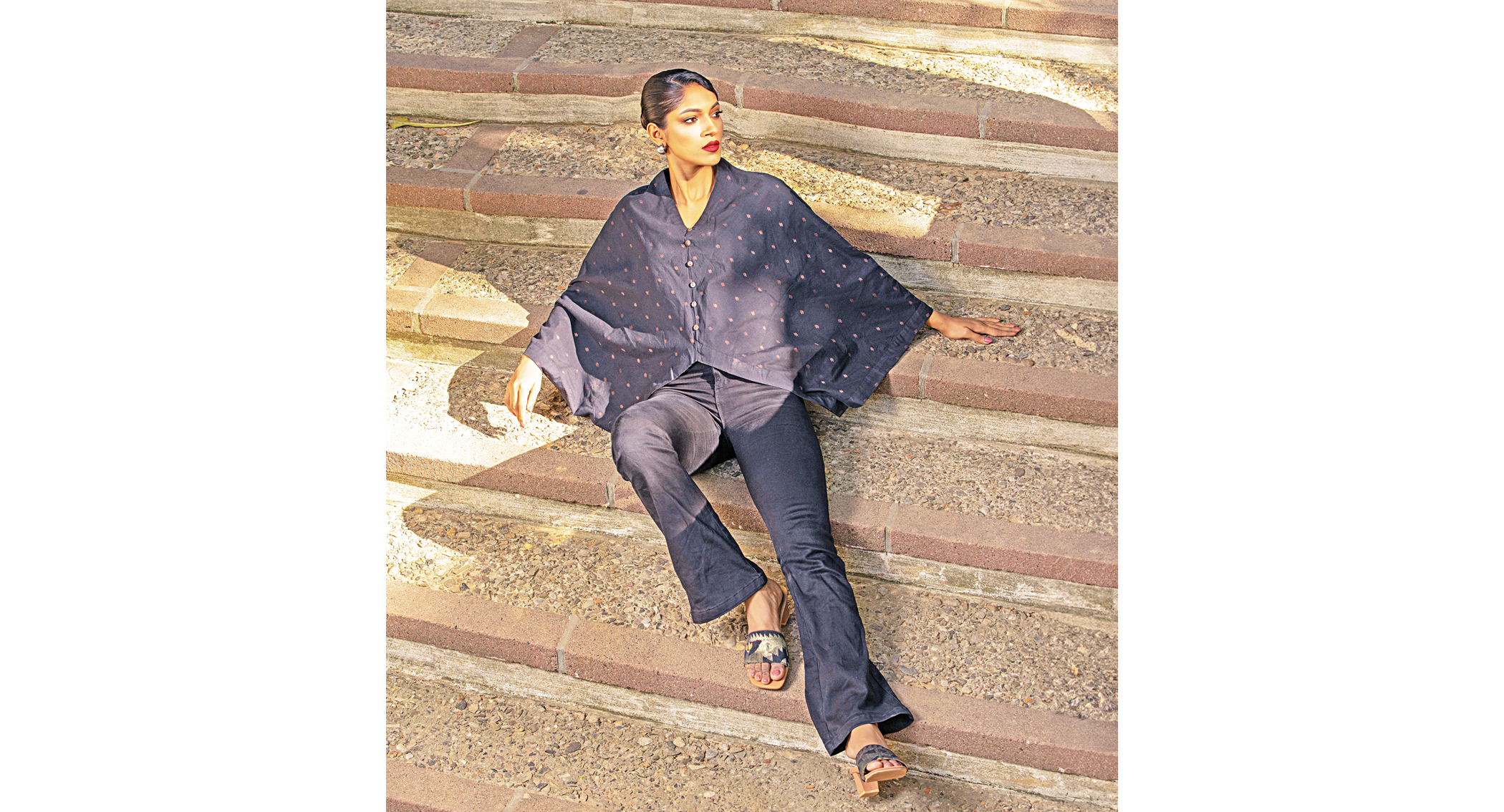

Photo: Adnan Rahman

Model: Proma & Surjo

Wardrobe: Bene Bou & Siz by FF

Styling & direction: Sonia Yeasmin Isha

Makeup: Sumon

Hair: Nayon

Location: Zinda Park

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments