Lohakath

The first time I saw lohakath was some years ago during monsoon on my way to Padma Resort with friends. About an hour from Dhaka, near Louhojong, I noticed roadside groves of tall, elegant trees with leaves of deep green. My friend Micky informed me they were lohakath trees, so called because the wood was so hard that it was impossible to hammer a nail (loha) into the wood.

That was my first encounter with lohakath whose botanical name is xylia xylocarpa. The tree belongs to the large fabaceae family of plants – a family that includes peas and legumes. What surprised me is that within the family, lohakath occupies a slot in the mimosideae sub-family. After all, the tiny mimosa (lojjaboti) and this tall tree had very little in common.

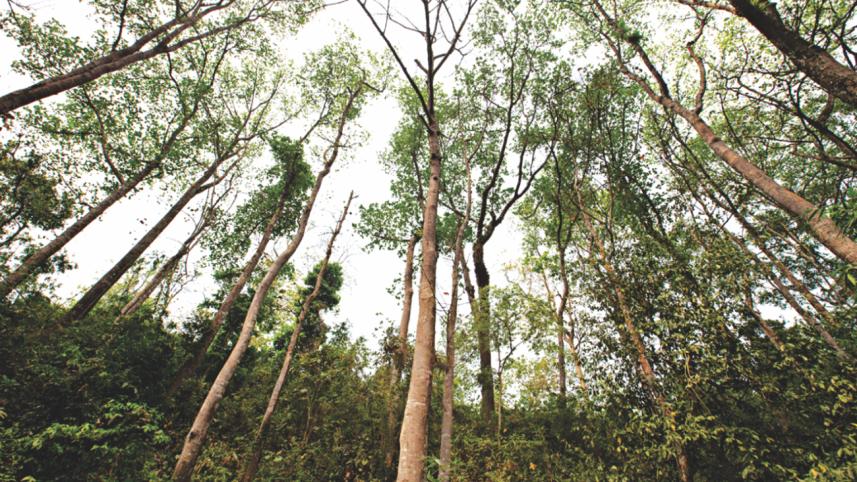

Lohakath can grow very tall (40 metres) and attain a girth of perhaps a metre. Branches are sparse and start growing at a substantial height. They radiate from the trunk allowing sunlight on the forest floor. A native to tropical Asia, lohakath thrives on higher land, particularly hilly, well-drained terrain.

I saw the most impressive lohakath trees in Lawacherra National Park. I had gone there looking for pig-tailed macaques. Having spotted and photographed them quickly, I found myself with free time to wander the trails. A few hundred feet from the entrance, to the left, was a grove of lohakath, magnificently shooting up to the sky.

What were they doing here in the park? It turns out that lohakath was planted in Lawacherra in the 1950s by the Forest Department. During that time, it was a popular choice for Forest Department plantations. Lohakath groves can also be found in Satchari, Rema-Kalenga and other protected forests and plantations of Sylhet, as well as in forests in Chittagong.

The wood of lohakath, coloured an attractive red, is very strong and useful for heavy-duty uses such as construction, railway slippers and boats. Lohakath bark is used in traditional medicine for a slew of illnesses including diarrhoea and fever.

Lohakath has another potential benefit. Normally, it is difficult to grow other plants on the ground between tall trees because sunlight cannot reach them. But because of the sparse density of lohakath branches, it might be possible to grow crops such as vegetables and strawberries in the ground between the trees in lohakath groves. Scientists have discovered that as long as they are not planted too close to the base of the trees, the yield of these crops planted in gaps among lohakath trees is comparable to those grown in open land. This opens the possibility of interplanting other cash crops among lohakath trees, important in Bangladesh where acreage is at a premium.

So, why is it that we don't see more of this elegant tree?

The main reason seems to be other hardwood trees such as acacia auriculiformis (akashmoni), which yields similar if not better quality timber while growing faster than lohakath. It is also easier for nurseries to grow saplings of akashmoni than lohakath. Thus, for economic reasons, akashmoni – and some other hardwood trees – are more popular than lohakath in our countryside.

Be that as it may, I am certainly grateful to those who planted the lohakath trees in Lawacherra, for their beauty is memorable.

www.facebook.com/tangents.ikabir.b

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments