The untold story behind 1971’s two most haunting photographs

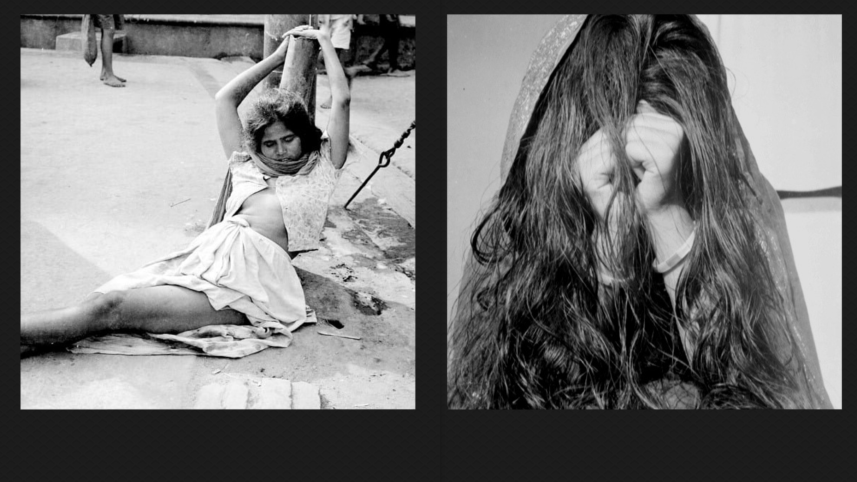

With dishevelled hair and clenched fists shielding her face, she tries to hide herself. Her scarf lies over her head like a small umbrella. Light slips through the window and falls across her body. On a day in May 1971, at Mymensingh Medical College Hospital, Naib Uddin Ahmed photographed several black-and-white images of the girl whose face was covered. A few months later, one of these photographs was published in the world-renowned newspaper The Washington Post. After its publication, the world was shaken. People everywhere came to know about the brutal sexual violence inflicted upon vulnerable Bangladeshi women during the Liberation War. Because the image was published, Naib Uddin's life came under threat. Even when standing at the door of death, he refused to reveal where he had hidden the negative. In the years following the Liberation War, the photograph came to be recognised as a symbolic portrait of Bangladesh's birangonas — the women subjected to sexual violence during the war.

Even so many years after the war, some still insist that the photograph was staged. A few even claim it was taken after the war with a model. Yet during his lifetime, Naib Uddin explained the full story of this image. On 9 December 1998, Prothom Alo's Wednesday supplement Narimoncho published a report titled How This Liberation War Photograph Was Taken. The report, written by journalist Mehedi Masud, was based on an interview with Naib Uddin.

Mehedi asked him, "For many years people have been saying — or you may call it an allegation — that this widely discussed photograph was arranged or staged. What do you say to that?" Naib Uddin replied, "During the Liberation War, the question of staging such a photograph simply never arose. In reality, the horrors were far worse." Mehedi Masud asked him for the girl's name, but Naib Uddin refused to reveal it. "Just assume some name," he said. He did, however, describe in detail how, and under what circumstances, the photograph had been taken.

At the time, Naib Uddin was the chief photographer at the East Pakistan Agricultural University in Mymensingh (now Bangladesh Agricultural University). On 26 March 1971, Vice-Chancellor Dr Kazi Fazlur Rahim declared the university as "Independent Bangladesh Agricultural University". The news reached Dhaka Cantonment within moments. On 26 April, two battalions of soldiers arrived at the university. They declared the campus a regional command headquarters.

With the support of local collaborators including a section of Biharis, the occupation forces unleashed killing, looting, rape, and destruction across the city. In fear for their lives, university students, teachers, and staff fled. Although classes were suspended, the administration tried to keep essential operations running by reaching the officials who had taken shelter in nearby villages. Many returned to work on persuasion. Most believed the Pakistanis were their "brothers," that Muslims would not harm fellow Muslims. Trusting this, they continued going to office each day and sending their children to school and college.

Naib Uddin often saw a young girl on the road. She was lively by nature. As her father was his colleague, she affectionately called him "Uncle". One day, when she greeted him, Naib Uddin asked, "So many soldiers roam the campus — aren't you afraid to walk through them to get to college?" She replied, "There are no classes, but my father still forces me to go." On another day, she told him, "Uncle, the fields by the Brahmaputra are full of white kash flowers. Will you take a picture of me there?"

"Of course," Naib Uddin said.

Laughing, she added, "Uncle, that day I will also sing you a song."

Humming a line from the song — 'Bendhechi kasher guchchho-amra/ Gethhechi shefali-mala' — she walked away.

On 16 December 1971, the country was freed from enemy occupation. The girl had a cousin who was living in London at the time. For advanced treatment, her parents and relatives sent her to London to stay with him. Under treatment there, she made a full recovery. Later, she married that cousin. In his interview with Prothom Alo, Naib Uddin said he had heard that her married life had been quite happy. She became the mother of two children. She never returned to the independent country again.

A few days later, she disappeared. After much searching, one collaborator revealed that Pakistani soldiers had taken her away. With his help, she was rescued from Captain Anjum's bunker. Unconscious, she was admitted to Mymensingh Medical College Hospital. Hearing this, a crushing heaviness fell upon Naib Uddin's heart. He went to the hospital. Her hands and feet were tied to the bed. At times she writhed like a distraught madwoman. Her mother stood beside her, tears in her eyes. Seeing her, Naib Uddin felt like crying loudly — but he could not. His chest tightened with grief.

Naib Uddin wanted to take a photograph of the girl. Her mother initially protested: "Please do not photograph her in this condition." But Naib Uddin explained, "I will send her picture to newspaper offices. If this is published, the world will know of the atrocities committed by the Pakistanis." Hearing this, her mother said, "She has already lost everything — there is nothing left. But if publishing her photo can help stop the torture of other girls, then do it." She untied her daughter's hands. As soon as Naib Uddin raised his camera, the girl covered her face with her hands and hair. As though she no longer wished to show her face to anyone; as though she wanted to flee from the crowd of this world. With his Rolleiflex camera, Naib Uddin captured several frames of that gesture.

A representative of The Washington Post visited Mymensingh at that time. Naib Uddin learned this news from his friend, the artist Shahtab (nephew of Colonel Taher). Through Shahtab, he sent a print of the photograph to the foreign journalist, requesting that it be published. He also requested that his name not be mentioned. A few days later, the photograph was printed in The Washington Post. The world was stunned.

Meanwhile, the occupation forces erupted in rage — "Who sent this photograph? Who has such audacity?" Major Bukhari and Major Kayyum of the Pakistan Army's intelligence unit arrived in Mymensingh to investigate the incident. Although the photographer's name was not printed with the photograph, the two intelligence officers suspected Naib Uddin alone. They were certain that no one else in Mymensingh other than Naib Uddin could have taken such a picture. They went to Naib Uddin's office and began interrogating him. He was then taken away in a jeep. The jeep stopped in front of his house. They searched every corner of the house; they ransacked the furniture. But because they could not find the negative, Naib Uddin survived. Before leaving, they issued stern warnings. After this incident, Naib Uddin left the campus and took refuge in Charharipur village across the Brahmaputra River. From there, casting aside concern for his own life, he continued capturing the images of Pakistani barbarity on the enchanted reel of his camera.

On 16 December 1971, the country was freed from enemy occupation. The girl had a cousin who was living in London at the time. For advanced treatment, her parents and relatives sent her to London to stay with him. Under treatment there, she made a full recovery. Later, she married that cousin. In his interview with Prothom Alo, Naib Uddin said he had heard that her married life had been quite happy. She became the mother of two children. She never returned to the independent country again.

After the country's independence, on 26 March 1972, the daily Purbodesh published its Independence Day edition. On the cover of that issue, four photographs including Naib Uddin's image were printed. On 16 December 1973, the Victory Day issue of the daily Bangla published a visual narrative titled Bhuli Nai (not forgotten); this photograph was displayed at the top of that story. On 26 March 1975, the Independence Day issue of the daily Bangla also published the photograph with the caption On That Day in '71. Nowhere did Naib Uddin reveal the girl's name or identity. Twenty days before his death, in November 2009, Naib Uddin's photo album Amar Bangla was published. In the chapter titled Ajeyo Bangla (the undefeated Bengal), he wrote: "When I remember Shahana, I still cannot keep myself steady. Her helpless cries in the hospital still strike hard against the walls of my ears."

From various bunkers across the vast university grounds, 15 women were rescued. The next morning, Naib Uddin set out with his camera. Walking past the killing field, he heard voices: "The boys are saying — the country has been freed, the country has been freed; come out from inside." A few women, covering their faces, ran in different directions. One girl crawled out of a bunker. She had very little clothing on her. She could barely walk. A short distance ahead, she sat down by a lamppost. Leaning against a broken pillar, she tried to look upwards. Sunlight fell upon her face. But she was unable to lift her gaze. Exhaustion forced her eyes shut.

Another photograph deeply unsettled Naib Uddin's heart. The heartbreaking portrait of a raped and defenceless Bangali woman became the closing signature of his photographic journey. Afterwards, he occasionally went out with his beloved Rolleiflex to take pictures, but he could never photograph as he once had. Whenever the subject of this photograph arose during interviews, his pained eyes would moisten. Muttering to himself, he would say, "How horrific, how horrific were the crimes committed by the occupation forces — yet the country has forgotten everything!"

In the Prothom Alo Narimoncho interview, Naib Uddin also elaborated on this second photograph. It was 10 December 1971. Indian soldiers and freedom fighters fought the occupation forces throughout the day. At 4 pm, defeated in battle, the occupation troops fled. In celebration of victory, the allied forces and freedom fighters hoisted the flag of Bangladesh on the campus of the Agricultural University. Afterwards, under the leadership of Brigadier Sanat Singh of the Indian Army, a rescue operation began. From various bunkers across the vast university grounds, 15 women were rescued. The next morning, Naib Uddin set out with his camera. Walking past the killing field, he heard voices: "The boys are saying — the country has been freed, the country has been freed; come out from inside." A few women, covering their faces, ran in different directions. One girl crawled out of a bunker. She had very little clothing on her. She could barely walk. A short distance ahead, she sat down by a lamppost. Leaning against a broken pillar, she tried to look upwards. Sunlight fell upon her face. But she was unable to lift her gaze. Exhaustion forced her eyes shut.

Naib Uddin went to her and tied the strap of her petticoat. She realised that someone had come to stand beside her. She said nothing, only lowered her head. Her hands and body bore scratch marks. Naib Uddin took several photographs of her. From a distance, a few Indian soldiers noticed what was happening. They ran up and said, "Hey, what are you doing...!" They tried to stop him from photographing. Meanwhile, one soldier arrived carrying a blanket. The girl was wrapped in the blanket and lifted onto a truck.

About two years later, one morning, an unfamiliar girl arrived at Naib Uddin's government quarters. From her attire, he realised she was from the Hindu community. Placing both hands on her forehead, bowing her head, she said, "Do you recognise me?"

Naib Uddin shook his head.

After a pause, she said, "I found your address after asking many people."

She reminded him of that day's incident.

"I recovered a few months ago and returned home. My husband accepted me. But people in our community did not take the matter kindly. So we have decided to leave the country. Before going, I felt I should come and tell you."

Naib Uddin remained staring at her face — unmoving, like stone.

Shahadat Parvez is a photographer and researcher. The article is translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments