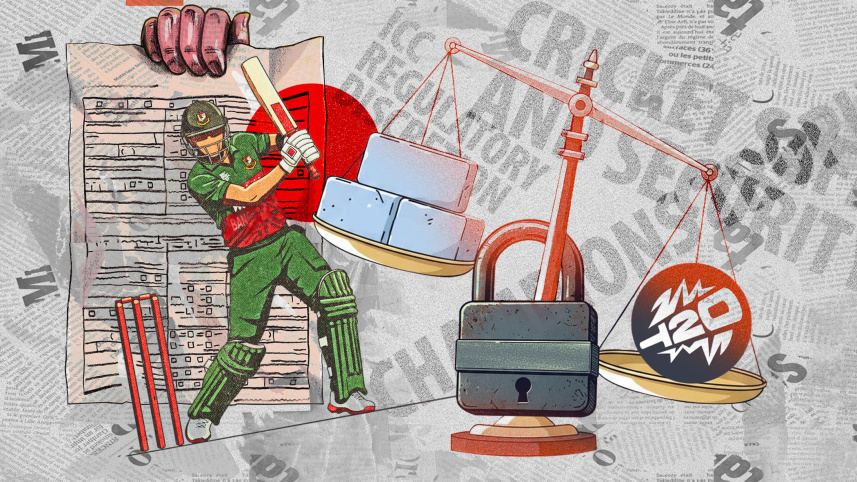

Bangladesh’s T20 snub: ICC failed a key test of sporting governance

International sport depends on a simple bargain: athletes accept risks, including physical and monetary, but governing bodies accept responsibility. When that bargain fractures, the question of credibility follows. The International Cricket Council’s (ICC) handling of Bangladesh’s request to relocate the country’s matches for the Men’s T20 World Cup from India to tournament co-host Sri Lanka due to security concerns—and its subsequent decision to replace Bangladesh with Scotland—represents one of the most consequential governance tests that cricket has faced in recent years. The controversy is not about diplomacy or rivalry, but about whether global sports regulators still operate within the constraints of fairness, consistency, and reasoned discretion that modern sports law demands.

Bangladesh’s request was framed as a security precaution, supported by government advice and recent precedents within cricket itself. Changing venues is not exceptional in the sport’s history; it is a recognised move for managing geopolitical and security risks. Pakistan’s frequent venue adjustments,Sri Lanka’s war-era relocations, and multiple ICC events staged outside the territory of host nations all testify to that reality. What makes this episode an issue is not that the ICC disagreed with Bangladesh’s assessment—regulators are entitled to disagree—but that it escalated disagreement to exclusion without publicly demonstrating why less disruptive alternatives were unworkable.

The ICC has argued that it conducted internal security assessments and found no credible threat warranting relocation. That may be so, but in regulatory governance, assertion is not explanation. Modern sports governance, shaped increasingly by the jurisprudence of the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), requires decision-makers to show not merely that they considered an issue, but how they weighed competing interests. Transparency in this regard is not a courtesy; it is a legal safeguard.

CAS panels have consistently held that international federations exercise a form of quasi-public power. With that power comes obligation. In FC Sion v FIFA, CAS stressed that governing bodies must provide reasoned and transparent decisions, particularly where the consequences for participants are severe. Exclusion from a global tournament is among the most severe sanctions available in sport. The ICC rejected relocation of matches without making the independent security assessment public, without demonstrating proportionality, and without showing that graduated remedies had been exhausted. The message, intentional or not, was that compliance mattered more than safety concerns raised in good faith.

Replacing a qualified team is much more than administrative housekeeping; it is the regulatory equivalent of a nuclear option. CAS jurisprudence is unambiguous on this point. In Matuzalem Francelino da Silva v FIFA, the panel rejected excessive regulatory discretion and held that sanctions must be proportionate and must not violate fundamental rights, including the right to pursue one’s profession. Although the case concerned football, its principles apply across sports. The proportionality test requires regulators to ask three questions: i) whether the measure is suitable to achieve a legitimate aim; ii) if it is necessary, or if less restrictive alternatives are available; and iii) whether it imposes an excessive burden relative to its objective. Applied here, the ICC’s decision struggles at the second hurdle.

Then there is the matter of consistency. When rules are applied unevenly, trust erodes, especially among smaller or less powerful member states.

In Guillermo Cañas v ATP Tour, CAS recognised that inconsistent application of regulations undermines regulatory legitimacy and may give rise to legitimate expectations. Bangladesh could reasonably argue that the ICC’s long reliance on neutral venues created an expectation that similar accommodation would be available when comparable concerns arose. This is not an argument for automatic approval, but for consideration with equal seriousness. When India refused to play in Pakistan, citing security concerns and political tensions, it was treated as a systemic challenge to be managed. Bangladesh’s concern about playing in India was treated as an obstacle to be removed.

This distinction matters. Replacing a qualified team with a non-qualified one—without disciplinary proceedings, without formal sanctions, and without an appealable decision grounded in published reasoning—stretches the ICC’s regulatory discretion to its limits. It also exposes the organisation to legal risk, even though Bangladesh has signalled that it will take no further action beyond what’s already done. Under ICC regulations, disputes ultimately fall within CAS jurisdiction. CAS rarely intervenes in sporting merits, but it intervenes readily where procedure, proportionality, or consistency fail. Remedies could include annulment of decisions, declaratory relief, or compensation—outcomes that would damage the ICC far more than a negotiated venue compromise ever could.

The ICC’s decision has also alarmed player representatives. The World Cricketers’ Association (WCA) has warned that punishing teams for raising safety concerns creates a chilling effect: players and boards learn that silence is safer than candour. Neutral venues, security bubbles, and independent assessments were not gifts from governance; they were concessions wrested by past experiences. When a governing body signals that safety concerns will be met with replacement rather than mitigation, it disincentivises transparency.

This controversy should not be misread as a geopolitical quarrel between boards or states. It is a policy failure rooted in centralisation of power without corresponding accountability. The ICC has spent the past decade consolidating authority over scheduling, revenue distribution, and tournament design. Centralisation can bring efficiency, but only if matched by transparency and restraint. Otherwise, it becomes coercive.

The ICC, therefore, needs a course correction. First, the ICC should publish a clear framework for handling security-based relocation requests, including independent assessments and graduated remedies. Second, it should reaffirm that neutral venues remain a legitimate governance tool, not a concession of last resort. Third, it should ensure that exclusion is treated as a sanction requiring heightened procedural safeguards, not an administrative shortcut. Cricket is a global game only so long as its governance treats all participants as equally entitled to safety, voice, and reasoned judgement. The Bangladesh episode suggests that assumption can no longer be taken for granted.

Md. Arifujjaman is deputy solicitor (additional district judge) at the Solicitor Wing of the Law and Justice Division under the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. He can be reached at arifujjaman.md@gmail.com

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments