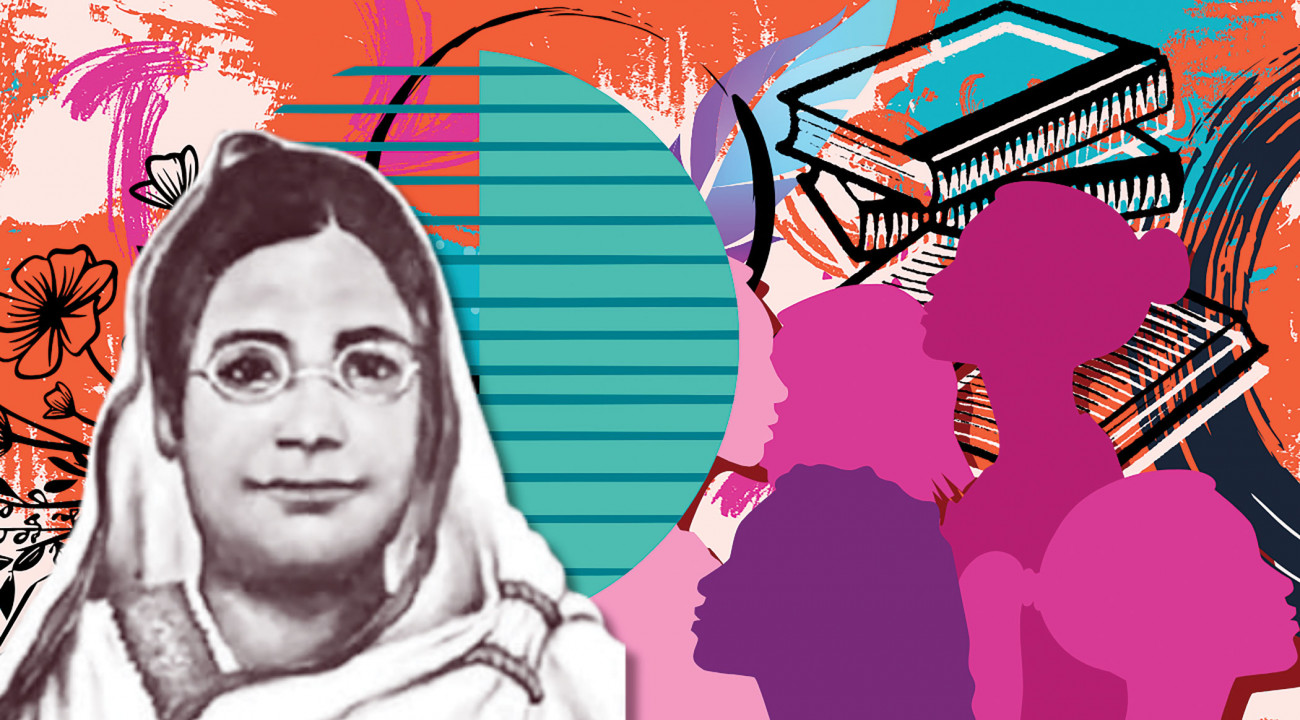

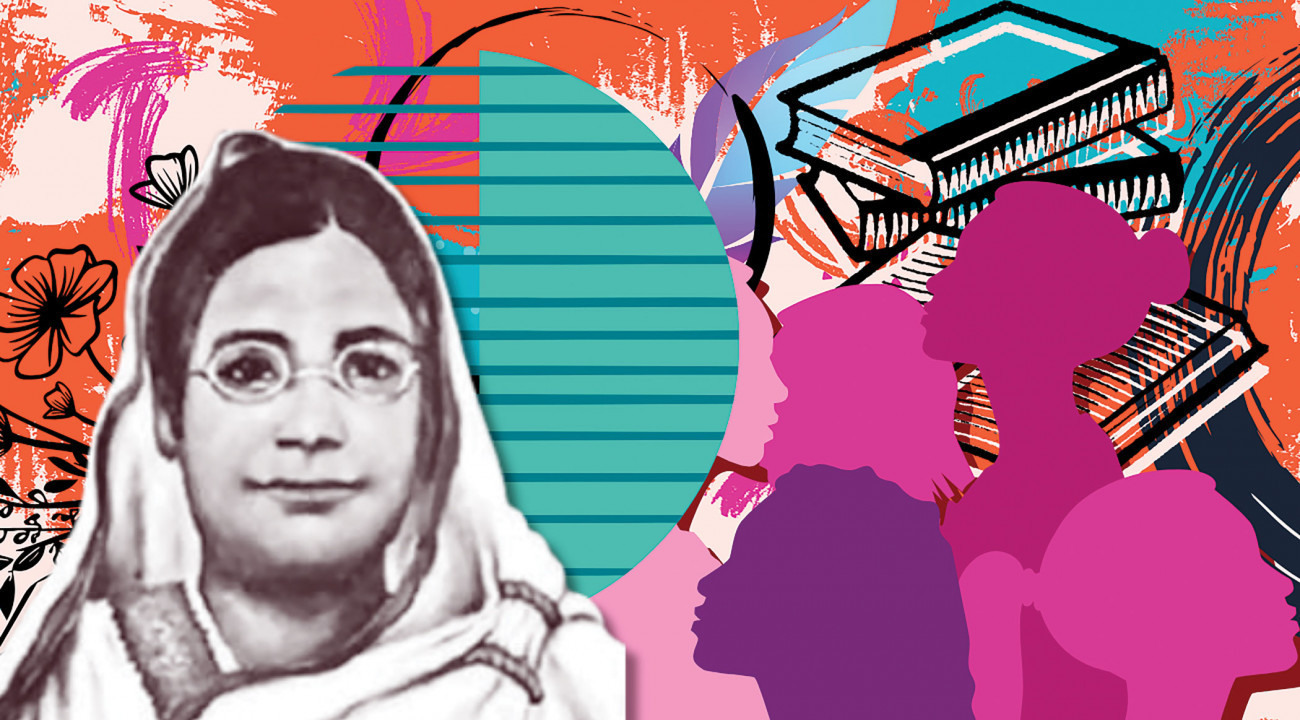

The nuisance of distorting Begum Rokeya’s legacy

When I first heard about the desecration of Roquiah Sakhawat Hossain, popularly known as Begum Rokeya, at Dhaka University in the aftermath of the July uprising, I paid it little attention, assuming it was a false flag operation aimed at discrediting the mass movement that ended an oppressive regime on August 5, 2024.

On the morning of November 11 this year, I delivered a speech on Begum Rokeya and Mary Wollstonecraft at my alma mater and former workplace, the Department of English at DU. While waiting for the event to begin, I was told that the defacing of Begum Rokeya's graffiti near Shamsun Nahar Hall in November last year had been a foolish act by an individual, not an organised attempt to malign Bangladesh's foremost woman writer. I later learned that a naive and ill-informed female student had committed the act, later apologised, and the matter was considered closed.

However, we are once again confronted with disruptive behaviour targeting Bangladesh's feminist icon. This time, it involved a university teacher. The individual, whose name matters little, defamed the devout Rokeya with preposterous accusations, seeking to portray her as an adversary of Islam.

Though nonsensical and presumably a publicity stunt, this attempt to sow dissonance between Rokeya and Islam has caused confusion about her religiosity. It struck me as a "mixed nuisance"—both a private and public irritant—affecting the wider public as well as me personally. As an academic who has studied and taught Begum Rokeya's works for decades, I can state with certainty that the university-affiliated critic's claims are the exact opposite of who she was.

Friends, both local and international, aware of my research interest in Begum Rokeya, continued to alert me to the controversy. I then came across a column by the editor of The Daily Star, titled "Bangladesh needs more dynamic Islamic discourse" (published on December 12, 2025), which touched on the issue. It suggested that the social media distraction surrounding Begum Rokeya's stance on Islam had shifted from triviality to seriousness, prompting me to respond.

I first learned about Islam in depth from the late Shah Abdul Hannan (1939-2021), a scholar versed in both Islamic sciences and worldly matters. Before meeting him in November 1994, my understanding of Rokeya's perspective on Islam was vague. As a second-year undergraduate, I attended Hannan's classes, where he discussed diverse scholarly debates on Islam. He devoted several sessions to examining Rokeya's work, presenting her as an Islamic reformist who opposed entrenched patriarchal and un-Islamic traditions in Bangalee Muslim society.

My own research later led me to the same conclusion: Begum Rokeya criticised cultural distortions masquerading as Islam, not the religion itself. In other words, she distinguished between "ethical Islam" and "establishment Islam," as Leila Ahmed terms them in Women and Gender in Islam (1992). Hannan also introduced us to Begum Rokeya's May 1931 essay, titled "Dhangsher Pathe Bangiya Muslim," which I later translated as "Bengal Muslims on the Way to Ruin"(2019). His discussion sparked my interest in her work, shaping my future research trajectory.

During my PhD in comparative literature at the University of Portsmouth (2007), I compared Rokeya's feminist ideas with those of Mary Wollstonecraft, Virginia Woolf, Attia Hosain, and Monica Ali. I have co-edited, jointly with Professor Mohammad A Quayum of Flinders University, and contributed to A Feminist Foremother: Critical Essays on Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (2017). In addition to numerous newspaper and magazine essays, I have authored journal articles on Rokeya published by Sage, Routledge, and the University of Florida.

Begum Rokeya's oeuvre does contain statements which, if decontextualised or interpreted simplistically, might seem to place her outside Islam. To avoid misrepresentation, it is crucial to read her writings critically and holistically rather than selectively. She employed the framework of Islam to promote women's education and rights. For instance, in her presidential speech at the Bengal Women's Education Conference in 1926, she stated: "The person who spoke first for equal education for men and women is our Prophet. He made it compulsory for both men and women to acquire knowledge."

She added, "The opponents of women's education say that, if educated women become imprudent and obstinate. Woe to them! They call themselves Muslims but go against fundamental precepts of Islam. If men do not go astray obtaining education, why will women?"

In Motichur-1, Rokeya observes: "In Arab society, where women were oppressed and female infanticide was widespread, Prophet Muhammad liberated them…. Alas! It is because of his absence [absence of his teachings] among us that we [women] are in such a despicable plight!"

Her Islamic framework is further evident in her English essay "God Gives, Man Robs" (1911): "THERE is a saying, 'Man proposes, God disposes,' but my bitter experience shows that God gives, Man Robs…. Our great Prophet has said, 'Talibul Ilm farizatu 'ala kulli Muslimeen-o-Muslimat' (i.e., it is the bounden duty of all Muslim males and females to acquire knowledge). But our brothers will not give us our proper share in education."

I could cite many more examples to demonstrate Begum Rokeya's commitment to advancing women's rights within an Islamic framework. Regarding her critical remarks, often used to suggest tension between her and Islam, I have previously written: "In places where she appears critical of religious authorities, her actual targets are pseudo-religious people and texts."

Given her righteous lifestyle and innumerable affirmations of her faith, it is inconceivable that she would question the divine origin of Islam's primary texts. Her pointed critiques were directed at misogynistic texts written by self-styled custodians of Islam.

In "Dhangsher Pathe Bangiya Muslim," Rokeya notes that books such as Rahe Najat (Path to Salvation) and Shonabhaner Puthi promoted women's unquestioned obedience to men. In her essay "Griho" (Home), she cites passages instructing women: "Never utter a word even if your husband wants to kill you," and "Husband is woman's guide and crown/Worship your husband as you do your Guide."

In the introduction to A Feminist Foremother, Professor Quayum and I clarify that when Rokeya wrote, "These are nothing but written by men," she referred to "numerous cheap and popular texts written by misogynists, clad in counterfeit religious garb" that promoted female subservience. Begum Rokeya did not question the authority of the Qur'an and Sunnah.

A proverb says: "If someone says it's raining and another person says it's dry, it's not your job to quote them both. It's your job to look out the window and find out which is true." Begum Rokeya's entire oeuvre is modest in volume. Let us read it, re-evaluate her relationship with Islam, and see for ourselves who she truly was.

Dr Md Mahmudul Hasan is professor of English language and literature at International Islamic University Malaysia. He can be reached at mmhasan@iium.edu.my.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments