Refusing constitution assembly oath defies people’s verdict

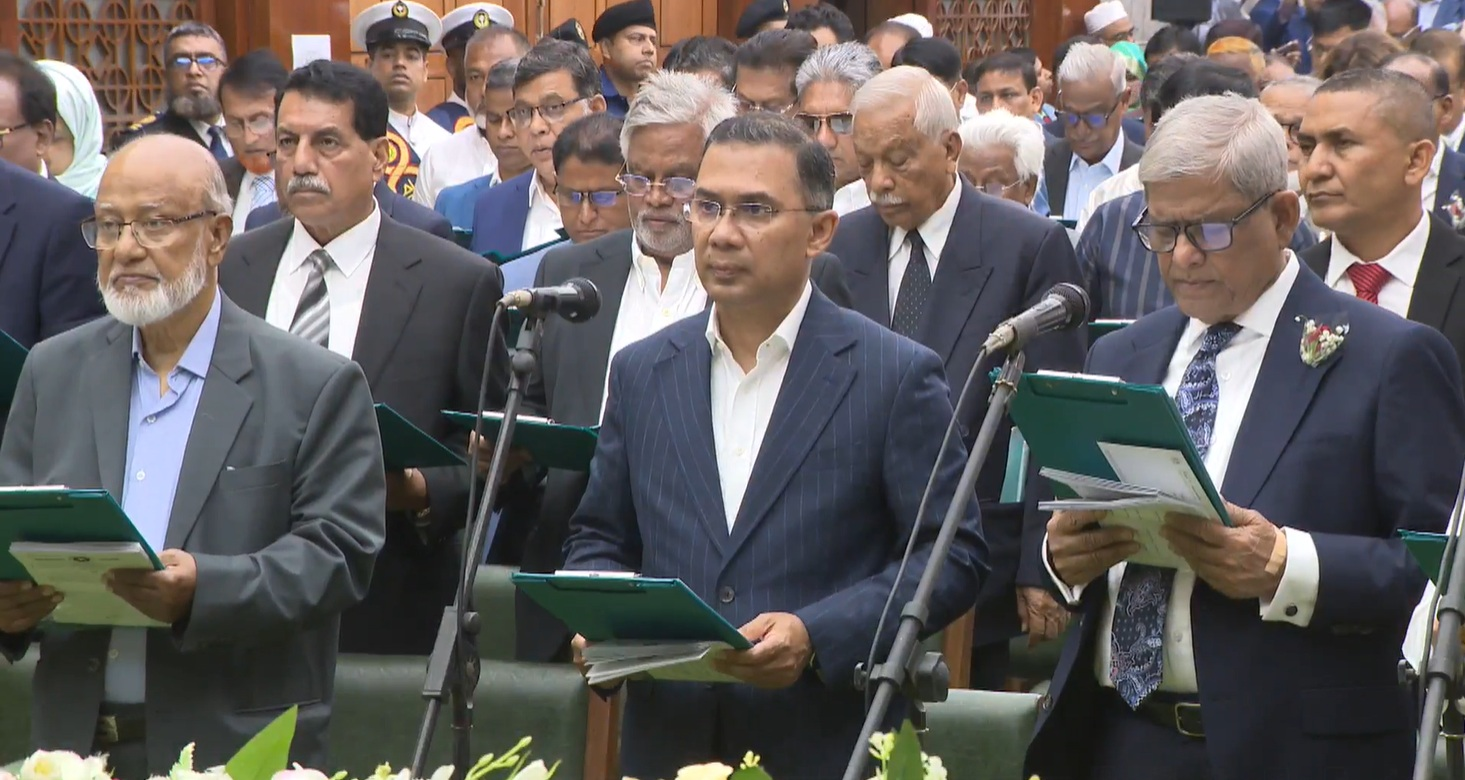

The newly elected BNP representatives’ refusal to take the oath as members of the Constitution Reform Assembly (CRA) on February 17 prevented what might have been a more meaningful new beginning for both the party and the country. BNP’s reason for not taking the oath—that the constitution does not provide for the CRA or the oath—is constitutionally unfounded. This is because the people are supreme, even above the constitution itself. Article 7 of the constitution recognises this principle, stating that all powers in the republic belong to the people. Accordingly, it is not tenable to argue the absence of constitutional provisions regarding something that the people have overwhelmingly approved in a referendum.

Furthermore, if we are to speak of the absence of provisions in the existing constitution, many actions taken since August 5, 2024, including the parliamentary election of February 12, are not covered by the constitution’s provisions. BNP does not appear to have any objection to most of those.

By refusing to take the oath, the ruling party has disregarded the people’s verdict in two ways.

First, more than two-thirds of the participants voted “Yes” in the referendum. Among the questions in the referendum was whether the people approved the July National Charter (Constitution Reform) Implementation Order, 2025. Since “Yes” received an overwhelming majority in the referendum, the constitution reform order gained the people’s approval. Among other matters, the formation and functions of the Constitution Reform Assembly (CRA) are significant parts of this order. Even the requirement to take an oath as a member of the CRA is included in the order, and the form of the oath is also provided for in the order. Since the order received public approval through the referendum, these provisions likewise have the people’s consent.

Second, there are strong grounds to say that the BNP is disregarding the people’s mandate because, before the election, BNP Chairman Tarique Rahman clearly called on the public to vote “Yes” on the election day. Just like BNP’s other electoral promises—such as the family card and agriculture card—its position in favour of “Yes” in the referendum was also an election pledge.

Therefore, it is reasonable to ask: if BNP had taken a position in favour of “No” instead of “Yes,” would it have been able to achieve the electoral success it did? It is quite possible that, had the BNP supported “No,” its performance in the election might not have been as strong. However, the situation that would have arisen if the referendum result had been “No” is now effectively what the nation is facing due to BNP’s refusal to take the oath. In other words, the party’s current position regarding the oath could have been justified only if the referendum result had been “No,” whereas in its election pledges, the BNP took a position in favour of “Yes.”

Thus, by disregarding the referendum outcome and by stepping back from its own electoral promise, the BNP has ignored the people’s mandate.

As a result, the process envisaged for implementing the constitutional reform has faced an initial setback. In this process, the first step was the issuance of the constitution reform order, the second step was the referendum, and the third step was the Constitution Reform Assembly. While the first two steps have been carried out, the third step remains pending.

But it can still be hoped that BNP representatives will take the oath. The party would face no disadvantage in doing so, as it will hold a two-thirds majority in the CRA.

If it is not possible to form the reform assembly, then constitutional reform will have to be implemented through the amendment of the constitution under Article 142. However, the problem of doing so is that the power to amend the constitution under Article 142 is limited, and it is not possible to alter the fundamental features of the constitution through it. This limitation arises from the basic structure doctrine which is a part of our constitutional law.

The basic structure doctrine is grounded in the idea that legislative power under the constitution is limited. Legislative power is derived from the constitution and must operate within its framework. In contrast, constituent power refers to the authority to create or fundamentally alter a constitution. This power resides with the people themselves, and the people have already exercised this power in the February 12 referendum.

Under Article 142 of the constitution, the parliament holds the power to amend the constitution. However, this is a derivative power and therefore subordinate to the constitution. As such, it cannot be used to alter the basic structure, which constitutes the inviolable core of the constitution.

In the past, amendments to the constitution have been declared unconstitutional by the courts by applying the basic structure doctrine. For example, the Eighth Amendment concerning the decentralisation of the High Court and the 13th Amendment concerning the caretaker government system were later declared unconstitutional.

It is worth noting that the court’s annulment of the 13th Amendment made the establishment of an authoritarian system in the country possible.

Therefore, implementing the extensive and fundamental reforms of the July charter through Article 142 procedure may not be the most sustainable approach.

As noted earlier, it is still possible for the BNP to take the oath, which could lead to a satisfactory resolution of the entire matter.

Dr Sharif Bhuiyan is senior advocate at the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, and has served as a member of the Constitution Reform Commission and as a legal expert for the National Consensus Commission.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments