From fear to trust: Why policing must change now

When Institutions Serve Power, Not People

In Why Nations Fail, Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argue that countries suffering from poor governance do so not because of geography, climate, environment, or culture, but because of the extractive nature of their institutions. Such institutions are designed to serve narrow elite interests, repress the broader population, and often carry deep colonial legacies. Bangladesh fits this diagnosis in many respects, particularly in the functioning of its state institutions.

The police, as an institution inherited from and shaped by colonial governance, was never designed to serve citizens as rights-bearing individuals. Instead, it evolved as an instrument to protect power and maintain control, rendering human rights largely irrelevant to its operational logic. Over the years, this extractive character has manifested in grave abuses: extrajudicial killings — most notably through the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), enforced disappearances, kneecapping, fabricated cases, and inhumane torture. In many instances, these practices were deployed not to uphold law and order, but to suppress political opposition and silence dissent. In this sense, the police force has functioned less as a public service and more as an extractive arm of state power.

The July uprising exposed this reality in its most brutal form. One of its most painful revelations was that the police — an institution meant to protect citizens — had instead become a symbol of repression. The widespread use of force against protesters shattered any remaining public illusion of neutrality or professionalism. This rupture pushed police reform into the national spotlight and compelled the interim government to establish the Police Reform Commission, one of six reform commissions formed in the early phase of the transitional administration. The uprising thus did more than trigger political change; it forced a reckoning with the extractive foundations of policing itself and raised a fundamental question that Bangladesh can no longer avoid: can an institution built to serve power be transformed into one that serves the people?

Reflections from the Police Reform Commission: Institutional Resistance and the Limits of Reform

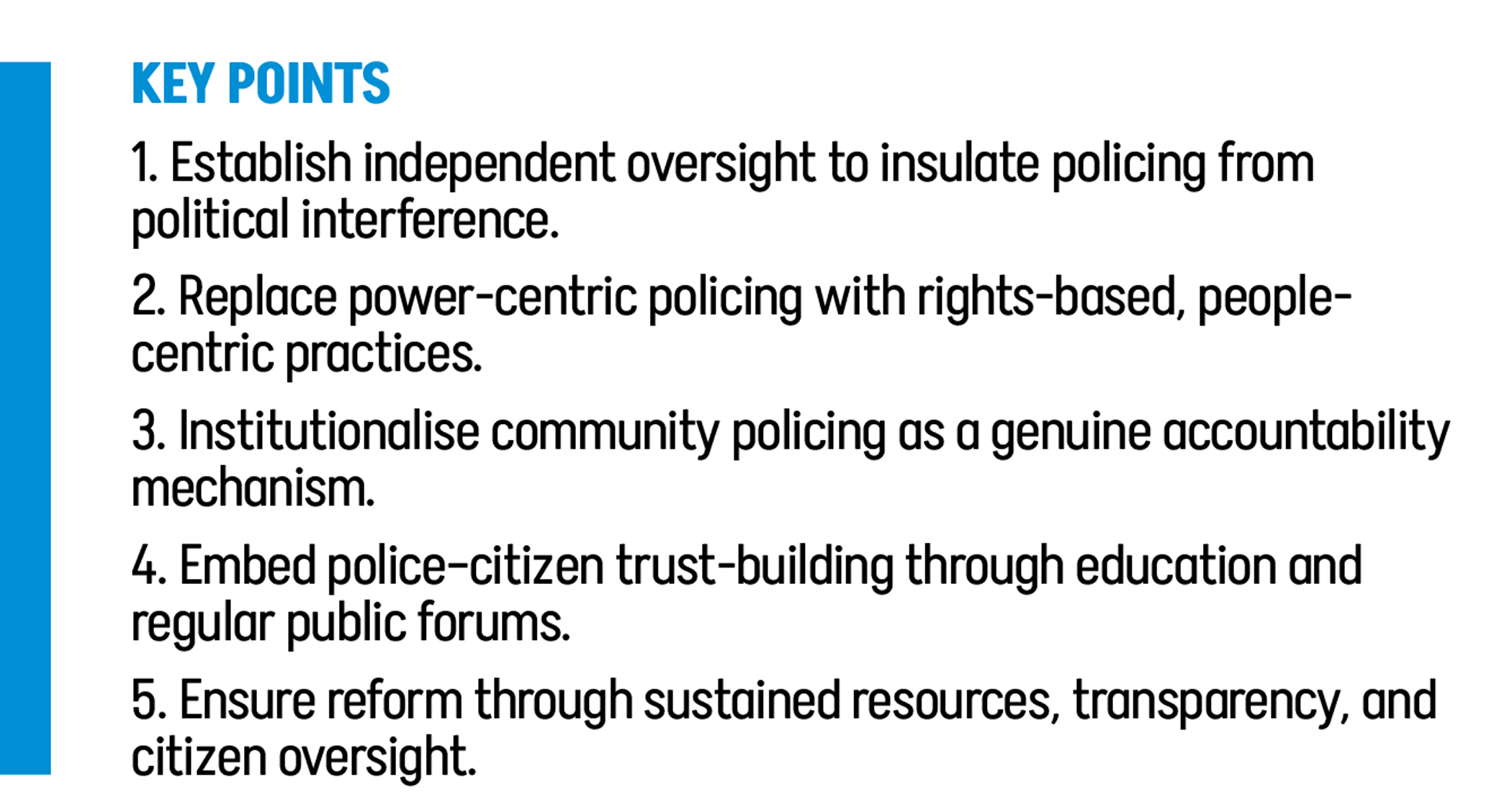

When work on the Police Reform Commission began, two key agendas dominated the table. The first was the formation of an Independent Police Commission. The logic was clear: such a body would insulate the police from political interference by acting as a buffer between the Ministry of Home Affairs and the police command structure. The brutal crackdown during the July–August mass uprising underscored how deeply political influence has eroded the credibility of the police.

The commission’s report did recommend the establishment of an Independent Police Commission, though it noted the dissent of the Ministry of Home Affairs. At the same time, the commission refrained from outlining a detailed structure or legal framework, stating that the idea “requires further examination by experts”. This hesitation attracted criticism for a lack of specificity. Yet the recommendation has, in effect, already been implemented: the interim government has passed the Police Commission Ordinance, 2025. Its effectiveness, however, remains an open question.

Another widely discussed demand in public discourse has been the repeal or updating of the colonial-era Police Act of 1861. Police representatives have repeatedly argued that a law designed to maintain colonial control — rather than democratic accountability or human rights — remains a troubling relic. While Police Headquarters submitted detailed reform proposals to the commission (annexed to the report), the commission itself stopped short of endorsing them directly, instead recommending that “outdated laws should be reviewed or replaced”.

Curiously, the Consensus Commission — tasked with harmonising the recommendations of all six reform commissions — initially sidelined police reform altogether, arguing that it could be achieved through executive orders alone. Only after sustained public pressure did the issue of a Police Commission re-enter the agenda and ultimately find a place in the July Charter.

From Technical Fixes to Transformative Reform

Through executive decisions, the interim government has also begun implementing several technical reforms recommended by the Police Reform Commission: the nationwide introduction of online GDs, the passage of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Ordinance, 2025, and the decision to conduct remand in glass-walled rooms, among others.

The commission further proposed a five-tier model for the use of force in crowd control, aligned with UN guidelines. The first two stages emphasise non-contact measures — verbal communication, negotiation, and physical barriers. The third stage introduces limited non-lethal force, including batons, gas sprays, water cannons, tear gas, sound grenades, smoke launchers, stun canisters, soft kinetic projectiles, pepper spray, shotguns, and electric pistols. The interim government has stated that training is underway to ensure police officers can properly follow these steps.

The home affairs adviser has also announced that police will no longer carry lethal weapons — a significant step forward. However, no official list clarifies what constitutes lethal versus non- or less-lethal weapons. This ambiguity must be addressed through sustained public scrutiny. If, for instance, pellet guns (chhorra guli) are classified as non-lethal, there must be strong civic resistance. Research by Sapran has already documented the devastating effects of such weapons: Abu Sayed, Tahmid, and many other July protesters lost their lives or eyesight to pellet injuries.

Yet beyond these technical reforms lies a set of far more transformative recommendations — largely overshadowed by debates over the Police Commission, the Police Act, and higher-profile reforms such as constitutional and electoral change. These overlooked proposals represent a paradigm shift in policing itself.

They appear in the report’s section titled “From Power-Centric Policing to People-Centric Policing” (pp. 68–78).

The Reform Report’s Overlooked Shift: From Power-Centric to People-Centric Policing

The section begins with a stark premise: the relationship between the police and the public is fundamentally broken. Many citizens do not understand their rights during police interactions, leaving them vulnerable to harassment and bribery. Over time, public perception has hardened to the point where the police are seen less as public servants and more as agents of coercion — a perception reinforced by their actions during the July uprising.

Building Police–Citizen Trust from the Classroom

One of the most practical yet transformative recommendations is to introduce public–police relationship content into the school curriculum. The goal is to build basic awareness of laws, fundamental rights, and the role of law enforcement from an early age. Such education could act as an icebreaker, nurturing empathy and dismantling mutual suspicion between future citizens and the police.

While curriculum reform is a medium- to long-term goal, immediate steps are possible. District-level police officers could begin visiting schools to hold awareness sessions, while selected students could visit police stations to observe everyday policing. These exchanges would humanise police officers in the eyes of young people — and remind officers of the communities they are meant to serve. Many superintendents of police, additional superintendents, and deputy commissioners we have spoken to are enthusiastic about this idea. What is needed now is a formal directive from the Ministry of Home Affairs to implement it nationwide.

Reforming Community Policing as a System of Checks and Balances

Another critical recommendation concerns the restructuring of community policing. In practice, community policing in Bangladesh has often been captured by local elites, turning committees into shields for misconduct rather than mechanisms of accountability.

The report calls for a paradigm shift: community policing must function as a system of checks and balances. Committees should be composed of diverse, credible, and non-partisan members, with clear mandates to monitor police conduct, convey public grievances, and bridge the gap between citizens and law enforcement. Rather than acting as political operatives or passive informants, members must become active participants in ensuring accountability.

This model is reinforced by the proposal for regular town hall meetings bringing together teachers, students, religious leaders, political representatives, and police officers. These forums would review local safety conditions, share police performance data, and document community concerns. Institutionalised as monthly meetings with public scorecards and incident reports, such forums could significantly strengthen trust through transparency and participation.

Resources and Institutional Support

The report also emphasises the need for proper budgetary allocation and infrastructure at the district level. Community policing training, school–police engagement, and public awareness campaigns require sustained institutional support. Without resources, even the most well-intentioned reforms risk remaining paper promises.

Accountability from Below: Reclaiming Policing for Citizens

For these reforms to succeed, coordinated leadership is essential — across the Ministry of Home Affairs, Police Headquarters, the Ministry of Education, local administration, civil society, and the media. The media, in particular, must go beyond episodic coverage and actively track the implementation of citizen-centric reforms.

Some may argue that reducing distance between police and citizens will weaken authority. But in a healthy democracy, discipline flows from respect for the law, not fear of law enforcement. A professional, rights-based police force earns legitimacy through accountability and service, not coercion.

The citizen-oriented proposals in the Police Reform Commission’s report must not be forgotten. If implemented seriously, they could lay the foundation for a policing model rooted in trust, transparency, and shared responsibility. As members of the Police Reform Commission, we carry a responsibility to bring these overlooked recommendations into public conversation — especially as elections draw near.

Real reform does not endure through executive orders or elite consensus alone. As Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson remind us, societies escape repression not by changing rulers, but by transforming the institutions that concentrate power in a few hands. Reform begins when institutions are forced to become inclusive — when citizens are informed, empowered, and prepared to hold authority to account. In the case of policing, this transformation cannot be imposed from the top down. It must grow from below, through public awareness, participation, and oversight. And if our laws fail to restrain the police, then it is the responsibility of citizens to do so. Only when policing is anchored in citizen accountability can Bangladesh move away from extractive control towards an institution that protects rights, commands legitimacy, and truly serves the people.

ASM Nasiruddin Elan Human rights activist and Director of Odhikar, a human-rights organization. He was a member of the Police Reform Commission.

Md. Zarif Rahman Researcher, columnist and activist. He currently serves as the Research Director at Sapran -- Safeguarding All Lives, a rights-based think tank. He previously served as a member and student representative on the Police Reform Commission of Bangladesh.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.