How one family keeps the 'Tepa Putul' tradition alive

Rag dolls made from tattered saris and handmade clay dolls called tepa putul were once the few tangible belongings young girls in rural Bangladesh ever had.

Silt and clay collected from riverbeds, along with scraps found around their homesteads, were the materials village children used to craft their own toys. They kept them with utmost care in shoeboxes or rusted tin containers.

But these are stories of once upon a time. Today, the face of toys has changed, and with it, the fate of traditional toys and crafts.

With imported culture flooding the market and the aggressive rise of plastic products, even village shelves are now filled with mass-produced items.

These seemingly insignificant clay dolls, tepa putul, once found across pastoral Bangladesh, along with other artisanal items, have now become part of our lost craft heritage.

I met Subodh Kumar Pal, a tepa putul artisan, at an upmarket fair in Dhaka last year. Since then, I have followed his work, and he eventually took me to his village, Boshontopur Palpara in Rajshahi.

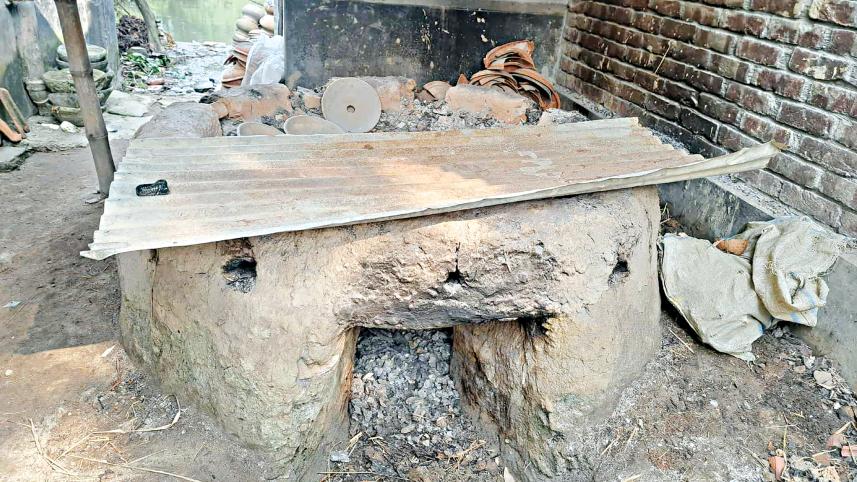

I am fascinated by heritage and folk keepsakes, and tepa putul is one cultural legacy I want to hold on to. Crafted by pressing raw clay with fingertips, dried in the sun, and then fired, tepa putul derives its name from the Bengali words tepa (pressing) and putul (doll), a nod to its simple finger-moulding process.

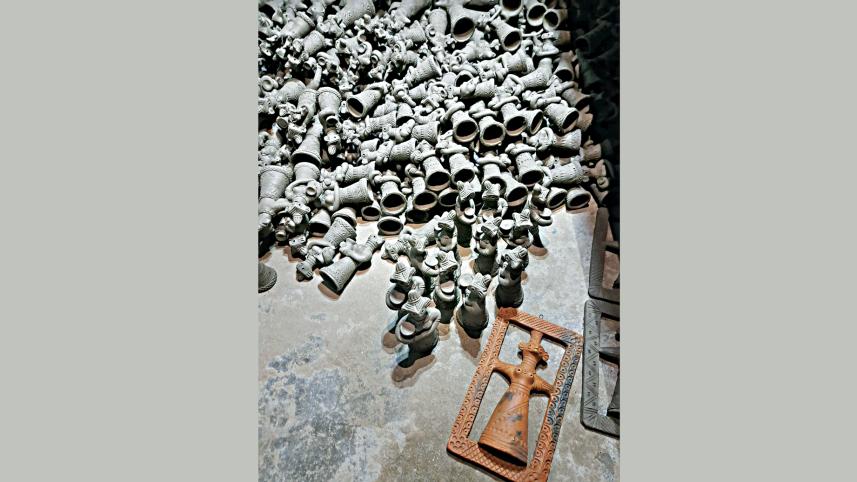

Figures of a mother and child, brides and grooms, farming families, or deities make up these rustic dolls. Unpainted and adorned only with ornamental clay markings, they are fine specimens of Bengal's folk artistry.

These crafts are not only cultural markers but also vital to the livelihoods of artisan communities.

A HEREDITARY CRAFT

Subodh's small family -- his son Shojib Kumar Pal and wife Bijli Rani Pal -- is the only one in Rajshahi still making tepa putul.

There are other potter families in the village, but each specialises in a different traditional craft. His neighbour, for instance, only makes Shoker er Hari or Hobby pots, decorative vessels used to store food or carry sweets during weddings and rituals.

Subodh, however, carries the torch for clay dolls. Bijli Rani has been making traditional clay dolls for 18 years and insists the craft requires a joyful mind.

"To do this kind of work, your mind must be in a good place. If the heart is heavy, the work won't turn out well. You must keep yourself happy," she says.

Her journey into mrit shilpo, the art of clay crafts, was shaped by her husband's family. Her father was a doll maker as well, though her mother never practised the craft. Bijli embraced it after marriage, continuing a fragile lineage of artisans.

An intricate doll can take two to three days to finish, while smaller ones are often made in batches of eight or ten over two days.

"The dolls that require painstaking work are priced at Tk 100 to Tk 400 depending on size, and Tk 3,000 to Tk 5,000 for the large ones. But profits are limited. People don't want to pay much for these delicate items. Only collectors who value heritage pay their true worth. Most prefer cheaper products," Subodh says.

In Rajshahi, only one family continues the craft; in Tangail, Somodarani Pal keeps it alive; in Kishoreganj, Sunil Pal does the same. Bijli says only a handful of artisans remain, though perhaps some practise quietly elsewhere. The tradition is on the verge of disappearance.

HAND-CRAFTING THEIR SURVIVAL PLAN

Sales in Subodh's village are modest, so the family relies on fairs in Dhaka, Sylhet, and government-sponsored exhibitions.

"I am gearing up for Independence Day, the Zainul Mela, and other fairs in Dhaka this December. These events are essential for our survival," he says.

Bijli and Subodh express deep gratitude to the organisers of the Zainul Mela and the Charukala (Fine Arts) authorities, who offer food, lodging, respect, and excellent sales opportunities – almost a lifeline for niche crafts.

"They value us the most. Without such fairs, our craft would have gone extinct years ago," they say.

"If Charukala stops including clay dolls in their fairs, we will lose everything," Bijli warns.

The challenges facing mrit shilpo are many. The widespread use of plastic for household items has eroded the market for clay products. Cooking pots, bowls, plates, and even matir chari – large clay tubs used for feeding cattle – have all been replaced by plastic alternatives.

Clay items are becoming rare, and their value is diminishing.

The financial strain on artisans remains a pressing issue. It takes almost three days of labour to complete one large doll. Every step is done by hand – moulding, polishing, finishing, and designing – and even collecting raw clay requires effort. River silt, once freely available, now requires payment to collect.

Most potters work independently, stocking items for yearly fairs, which remain their primary income source. Commissioned orders are rare. This raises the hard questions: how do they manage daily expenses, or pay helpers?

"The truth is, if I don't work, I don't eat. Courier services refuse to take responsibility for fragile clay items, which limits distribution and our income," Subodh says.

Clay crafts require time and artistic freedom. Electric wheels may help with larger items like pitchers or tubs, but they cannot replace the artisan's touch. Delicate work still relies entirely on hand finishing and creative insight.

Tepa putul is more than craftwork; it is a heritage skill passed down through generations. Subodh showed me an archetype of the first tepa putul made by his great-great-grandfather. The red-fired clay figure had only a pressed outline and simple dots for eyes. Over generations, intricate designs were added, shaping the doll we recognise today.

Subodh believes his son will eventually add his own creativity to this age-old tradition.

The story of Subodh and Bijli is emblematic of Bangladesh's endangered mrit shilpo. Their words reflect resilience and vulnerability. They reveal a devotion to craft despite low margins, cultural neglect, and systemic obstacles.

This tradition is sustained by festivals, a fragile network of artisans, and the stubborn persistence of those who refuse to let crafts like tepa putul vanish.

It is a way of life rooted in joy, patience, and heritage. Unfortunately, its future is threatened by rapid urbanisation and the social turmoil of the present.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments