The city that didn’t throw things away

In 1980s-90s Dhaka, “recycling” wasn’t a virtue you announced like a new gym membership in the first week of January. It was the background music of middle-class life.

We weren’t sitting around dinner tables discussing carbon footprints. “GDP” wasn’t something you heard on TV. The country was materially strapped, on paper and in practice. Bangladesh’s GDP per capita in 1990 was under US$ 300, which is a polite way of saying: everything had to stretch, especially the taka.

So, we stretched.

If you grew up middle-class in 1990s Dhaka, you knew the ritual: the start of the school year meant new books, and new books meant book covers you had to make with your own two hands. Child labour, sure. The raw material was old wall calendars, especially the glossy ones with scenic photos (Japanese mountains protecting a Bangla grammar book, globalisation at work). The book wasn’t only yours; it was a future hand-me-down. Your younger sibling, your neighbour’s kid, someone in the extended family ecosystem was waiting in the wings.

That’s the thing about that era: people weren’t buying things to discard them. Disposables existed, but they hadn’t staged a full cultural takeover. The city still behaved like objects had second lives. At home, glass bottles were repurposed for storing drinking water. Not because we were romantically attached to glass. Because the bottle still had utility, and Dhaka households have never been sentimental about utility.

Even “waste” had an afterlife.

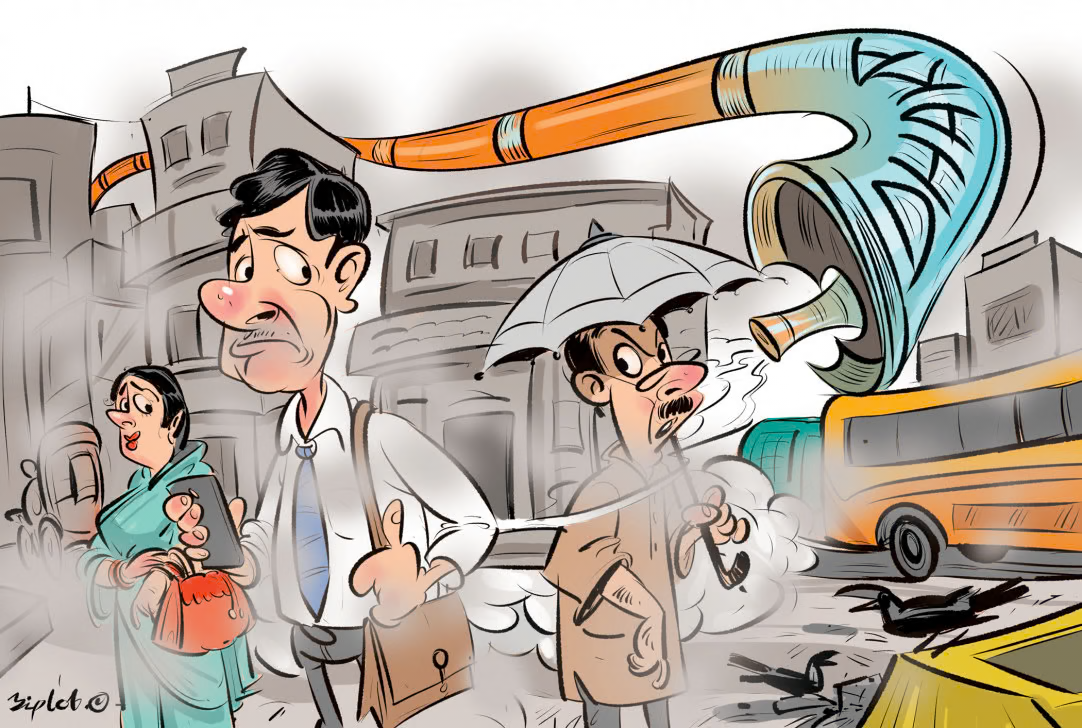

Old newspapers, broken aluminium utensils, empty jars, cardboard weren’t thrown out and forgotten. They were converted into cash. Door-to-door waste buyers made their rounds, buying household clutter for a meagre handful of taka.

In the early 2000s, research teams documenting Dhaka’s solid waste ecosystem described a large recycling workforce and a clear value chain -- collectors, buyers, and small recycling factories -- fuelled by precisely this kind of household-to-informal-sector exchange. One study (JICA’s Dhaka solid waste management work) estimated about 74,000 people engaged in recovering materials from waste, and explicitly noted the role of these “buyers” collecting waste from households in exchange for cash.

In other words, our “environmentalism” looked like a man with a sack and a loud voice. It was capitalism, but with reuse baked in, not as ideology, as necessity.

And then, Captain Planet arrived on TV like a blue-skinned conscience with a bright green mullet.

For a generation of Dhaka kids, this was the first time “the environment” showed up as a story with villains and stakes. Captain Planet and the Planeteers was packaged with a very clear moral universe: pollution and greed are the bad guys; kids have agency; and “the power is yours.” Even the episodes often ended with a little civic sermon, nudging viewers to be “part of the solution rather than the pollution.”

But here’s the great irony: we were already doing half the things Captain Planet preached, albeit without the vocabulary. We were reusing containers. We were extending product life. We were feeding an informal recycling market. We did not know the throwaway lifestyle. Yet.

We just didn’t call it “saving the planet.”

And that practice matters now more than ever, because the planet we watched on CRT televisions is no longer a cartoon crisis. Bangladesh is already paying immensely for real heat; a World Bank-linked finding reported by Reuters pegged the economic cost of rising heat in 2024 at around $1.78 billion, with Dhaka singled out as one of the world’s most heat-stressed cities.

Here’s the other uncomfortable truth: as Bangladesh moved up the income ladder, we imported the aesthetics of convenience. Disposables blew up, and the old culture of “keep it, you might need it” began to look unfashionable. We started treating objects as if they were born to become trash. Dhaka started flirting with being wasteful. As if wastefulness is a sign of progress.

What the ‘80s-‘90s generation carries, quietly, is a form of expertise: the instinct to look at an item and see its next possible life. The creativity to repurpose. The lack of shame in repairing.

The tragedy is that this intelligence has often been dismissed as “poor people habits,” when it’s actually a survival skill the rest of the world is now trying to rebrand as “circular economy.”

Dhaka didn’t learn recycling from global campaigns. Dhaka already had its own version, born out of necessity.

And now, when climate anxiety is very real and “sustainability” looks fashionable in an Instagram bio, the most radical thing we can do is admit: we’ve been here before. Just not with hashtags.

The power was ours all along.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments