BCS exams in need of reform

For as long as civilisations and empires have existed, there has been a bureaucracy. Early empires had governorships and officers loyal to the monarch who enforced the law of the land and, most importantly for any agrarian society, kept track of the grain being produced and distributed. The jobs, however, mostly went to the children of the nobility, who could afford an education. Court intrigue and nepotism also had a lot to do with it. It was China, during its Sui Dynasty (around 580 CE), that formalised the first known meritocratic system of appointing civil servants through a centralised civil service exam. This marked a democratisation in the bureaucracy, as candidates would be chosen through a competitive exam, rather than being appointed hereditarily.

The post-feudal centralised civil service on this subcontinent is, in large part, shaped in the image of the British Civil Service. After being exclusively ruled over by a mix of traditional and European bureaucrats in the company era, the then British Parliament set up the Macaulay Commission that formulated and inaugurated the first Imperial Civil Service (ICS) examination in 1853, open for all citizens of the empire aged 18 to 25.

The exam focused heavily on English as the primary language of the bureaucracy, along with Greek, Latin, Arabic, and other Indian languages as well. Civil servants required mastery over the language of the province they'd be posted to, as well as the language of the Crown. The ICS is the precursor of the modern Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) exams in India, the Central Superior Service (CSS) exam in Pakistan, and, from 1972 onwards, the Bangladesh Cadre Service (BCS) exam in Bangladesh. With an aim to keep the bureaucracy apolitical and to oversee the appointment and welfare of bureaucrats, the Bangladesh Public Service Commission (BPSC) was declared an independent commission in the newly drafted constitution, and the first exams in independent Bangladesh were held in 1972.

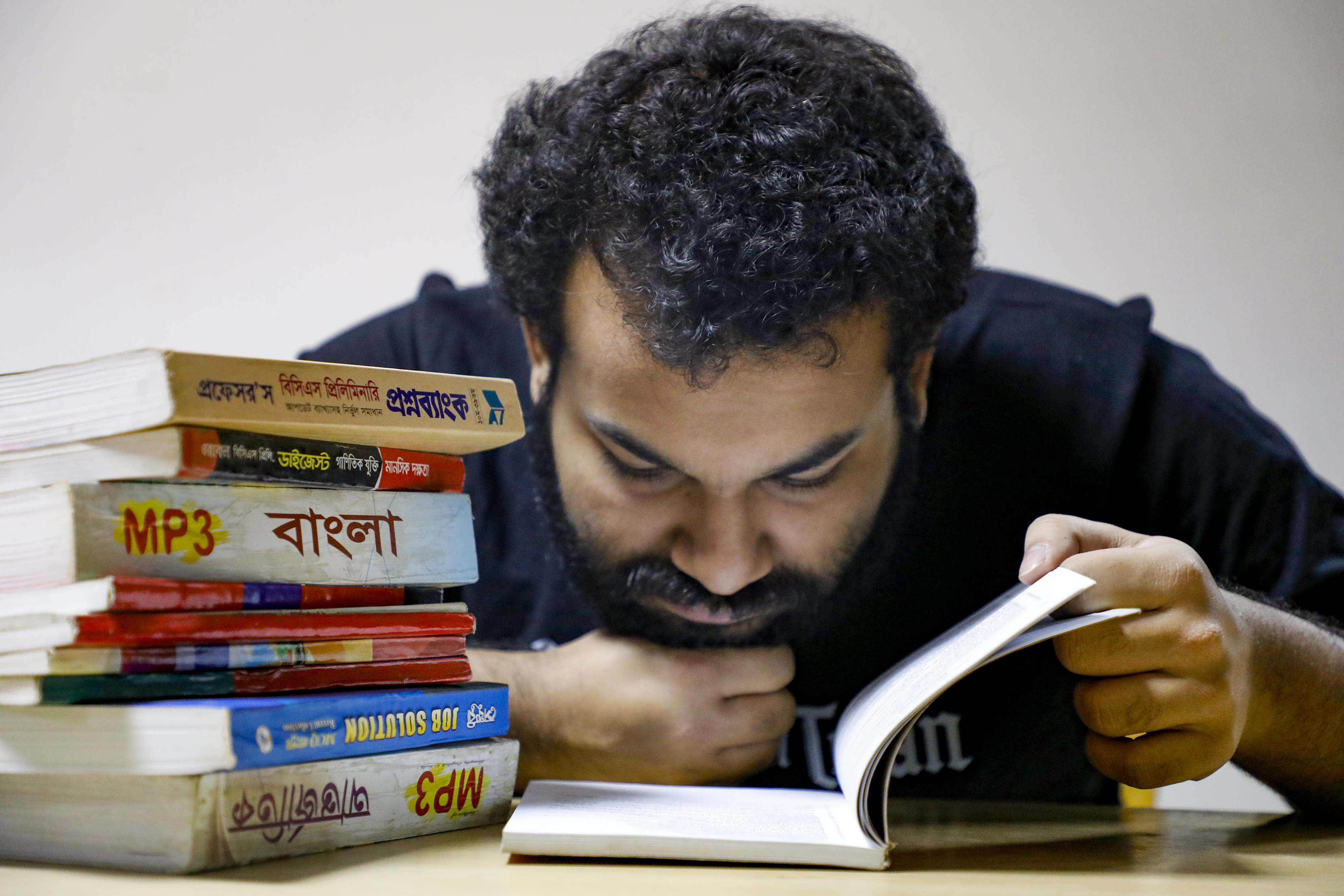

In total, 49 BCS exams have been held to date. Currently, there are 26 cadres of appointment, comprising 10 general cadres (such as administration, police, and taxation), 12 technical cadres (such as Health, Education, Agriculture), and four mixed cadres. Due to the exam being open for any citizen with a bachelor's degree, relative job security, and perceived social status, BCS government jobs still remain among the most coveted jobs in the country, especially for the middle class. In any given year, approximately 4.5 to five lakh applicants sit for the preliminary exams. A little more than one thousand applicants end up getting a job.

With an almost 0.2 percent appointment rate, the BCS exam is one of the toughest exams to crack. The exam is tough – but much of it still depends on memorising huge amounts of information. This requirement is something inherited from its predecessor, the ICS exams. Just like the British system, our civil service exams still lean hard on Bangla and English literature and grammar. In any given year, 70 out of 200 MCQ questions in the preliminary exams will be from Bangla and English, covering grammar and literature. 400 marks out of 900 in the written exams are allocated for Bangla and English.

Examining language proficiency is, of course, necessary for appointing a civil servant, but the predominance of language and literature in the exams suggests a unique knowledge of language-based trivia is required to hold a bureaucratic job. The methods of evaluation of language proficiency barely reflect the realities or responsibilities of a modern public service. They're more of a relic of the colonial era. In an attempt to thin out the crowd, questions from the literature portion have become arbitrary and cannot be said to reflect an actual mastery over language or literature.

Ironically, the UK has moved on towards a more modern skill-based appointment system for its own civil service, which tests verbal, numerical, and judgement skills through comprehensive tests. A larger emphasis is given to the interview portion and problem-solving. Therefore, their recruitment process is empirically more likely to bring out the right person for the job.

In accordance with global standards, recruitment exams in our private sector have rapidly evolved as well to assess both competence and character. A leading international bank, for instance, now requires all applicants to sit for a behavioural assessment exam even before CVs are screened. This early filter prioritises personality traits and cultural fit, narrowing the pool to candidates who are better aligned with the organisation's values.

Multinational companies follow similar models. Candidates first sit for tests measuring language proficiency and analytical ability. Those who clear this stage move on to a focus group discussion (FGD), where small groups tackle a case study under the supervision of a moderator. Here, recruiters observe how candidates think under pressure, negotiate disagreements, and contribute within a team. Candidates with the proper skillset move on to the interview round for one last round of scrutiny. Increasingly, employers are also adding practical tests, such as Excel assessments, to gauge whether candidates can perform the actual tasks required of them.

If the government hopes to build a more capable and productive civil service, it must rethink its recruitment model. Modernising the language proficiency tests with applied communication modules and comprehensive literature quizzes, increasing subject-based evaluation for technical cadres, and including FGD sessions before interviews would serve as improved tools of evaluation for our future bureaucrats. Modernising the BCS exam is no longer optional; it is essential that the BPSC ensures a system of examination fit for our era. We can hope that through necessary reformations, the bureaucracy of this republic will continue to be represented by our nation's best.

References:

1. Athens Journal of History (2025). The Chinese Imperial Examination System's Historical Significance: Why was it administered?

2. Britannica (May 12, 2025). Chinese civil service

3. Vajiram and Ravi (Nov 7, 2025). Evolution of Civil Services in India – Civil Services During British Rule

Tazrin is a Contributing Writer at The Daily Star. Remind her to take regular breaks at rashidtazrin1@gmail.com

Mehrab Jameeis a 5th-year medical student at Mugda Medical College and writes to keep himself sane. Reach him at mehrabjamee@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments