The face of an unknown woman in Rayerbazar

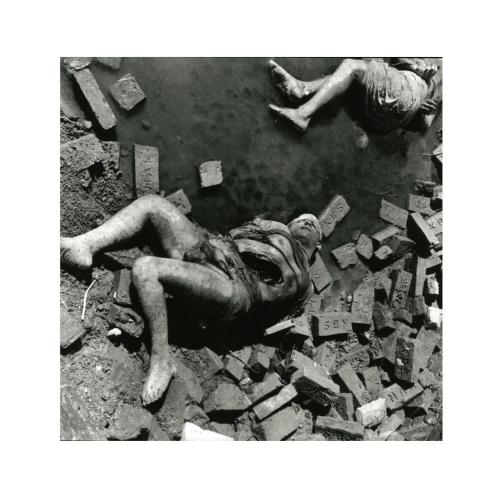

The afternoon after Victory Day. In the fading light, a sight in the abandoned brick kiln of Rayerbazar froze Rashid Talukder's blood. A body lay sunken in the muddy water of a pit, most of it submerged. Breaking through the layer of soil and hard brick dust, the face of a woman had surfaced like a mummy. A bullet wound marked her chest. Her body bore signs of torture. The left eye had been gouged out; the right remained shut. Her mouth hung open. As he pressed the shutter of his Rolleiflex, tears blurred Talukder's viewfinder. He wiped the glass with the handkerchief wrapped round his nose, then stepped into the muddy water, positioned the camera over her face, and took several vertical frames. Fifty-four years have passed. The identity of this unfortunate woman has never been found. Yet her anonymous face became one of the defining documents of the genocide in Bangladesh.

The black-and-white photograph of this woman—brutalised by the Pakistani occupation forces and their local collaborators—still silences every human feeling within us. For generations born long after the war, the image evokes a visceral hatred of the perpetrators and a desperate urge to learn the history of Bangladesh's liberation. Through this one photograph, Talukder provided a stark visual backdrop to that collective yearning. His Rolleiflex bore witness to many other historic moments of the Liberation War, making it impossible to study the visual history of 1971 without encountering his gaze.

For at least the last decade of his life, I had the privilege of knowing him closely. We photographed many political events side by side across Bangladesh. He liked riding pillion on my motorbike on our assignments. Between shots, he would share memories of his long career in journalism and the harsh years of the war. Through his camera, he spent his life searching for life itself. He wanted to make images that spoke of human experience. It is from those memories that I, the humbler one, have attempted to record this tragic chapter of Rayerbazar.

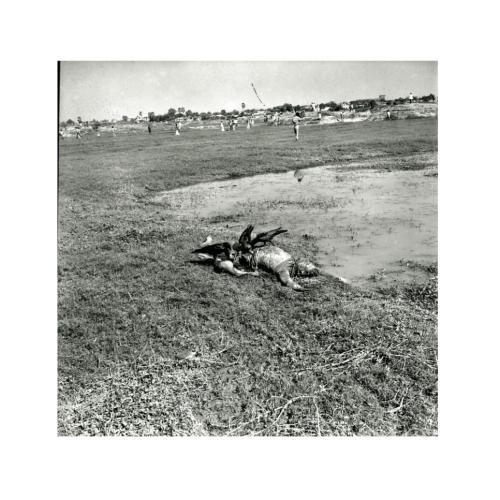

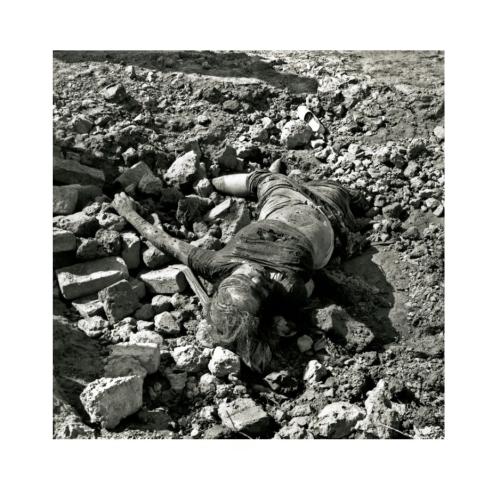

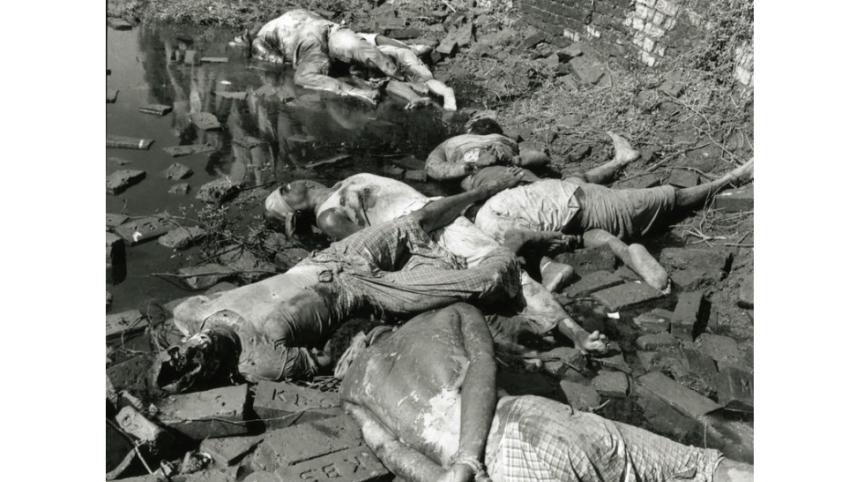

At dawn on 16 December, Rashid Talukder set out to take photographs with Michel Laurent, an American photographer from the Associated Press. All day they captured scenes of gunfire and jubilation. Shahjahan, a young man who lived in his home, was killed by the occupation forces later that afternoon. The joy of victory turned to grief for Talukder. The next day at noon, he heard of the massacre of intellectuals. News spread that hundreds of their bodies lay in Rayerbazar, Katasur, and Basila. Word travelled from mouth to mouth with the speed of wind. Overwhelmed by the weight of the moment, he reached Rayerbazar after midday. In front of a deserted kiln known as KBS, he saw hundreds of corpses. Some were blindfolded, some with tied hands; some had eyes gouged out; parts of faces had been slashed; others had their stomachs ripped open. Many had already become food for crows, kites, vultures, and wild dogs. Some skeletons lay scattered at the edges of the wetlands. He photographed until dusk descended.

As the staff photographer of Dainik Sangbad, he returned the next morning. Along with local journalists, representatives of the international press had also gathered. Waves of people rushed in search of missing loved ones. Instead of celebrating victory, a shadow of profound grief enveloped their hearts. Their wailing tore through Rayerbazar and its surroundings. Many fainted at the sight. Numerous bodies—mostly decomposed beyond recognition—were recovered that day from ponds, ditches, and pits across the area. Among the identified martyrs were Professor Munier Chowdhury, Professor Abul Kalam Azad, Professor Dr Abul Khair, eminent physician Professor Alim Chowdhury, Dr Mohammad Fazle Rabbi, journalist Syed Najmul Haque, and Awami League workers Mohammad Badiuzzaman, Mohammad Shahjahan, and Muhammad Yakub Mia. Talukder captured the final, harrowing moments of these intellectuals' lives through his lens.

Reports in Dainik Ittefaq and Dainik Bangla published on 19 December 1971 revealed that, when Bangladesh's victory became almost certain after nine months of war, the Pakistani army and their collaborators devised a grand plan to annihilate the nation's intellectual class. They prepared a list of 1,500 people. Like vicious predators, they raided homes and abducted countless teachers, doctors, journalists, writers, researchers, lawyers, scientists, political thinkers, and students. They were taken to various locations in Mohammadpur and Rayerbazar, blindfolded, bound, bayoneted, and shot. Ittefaq wrote: "From the age of Pharaoh to Hitler's gas chambers, we have heard tales of countless inhuman massacres. But the killing of the golden sons of Golden Bengal has overshadowed them all."

That same day, Dainik Bangla published a searing report titled "In What Language Shall We Describe the Brutality of the 'Al-Badr' Beasts?" The reporter's name was not mentioned. He wrote: "Before reaching Katasur, Rayerbazar, and Basila wetlands on Saturday morning, I had never understood how shattering grief can be. After the great cyclone of November 1970, I saw processions of thousands of corpses. Nature's fury left me devastated then. But here, at this killing field, witnessing the savagery of the Pakistani forces and their collaborators Al-Badr and Al-Shams, I felt paralysed with sorrow. Many of us journalists had survived only because we fled our homes. In the sea of bodies of loved ones, I felt as though I could see our own shadows. This too was meant to be our killing field."

To understand the context and horror of the intellectual killings in Bangladesh, the report's concluding lines are essential:

"Bodies were scattered across the vast field. In some places, several corpses lay in heaps. Women were among them. Most appeared two or three days old. In one spot, parts of limbs protruded from two half-buried bodies—older, by several days. One corpse after another. Some beheaded. Locals who had fled earlier told us that hundreds more bodies had been found near the Saat Gombuj Mosque and the Shia Imambara to the west. That area was still inaccessible—they said gunshots continued. Suddenly I heard sobbing. Beside me was the Australian journalist Mr Finlay. He was crying. An Indian journalist was crying. I was crying. Many others were crying. Standing at the killing field, the world of our sorrow had become an ocean."

After reading that deeply moving report in Dainik Bangla, I became eager to know the name of the journalist who had written it. I shared the matter with Ahmed Noor-e-Alam, a distinguished journalist of the 1960s now living in the United States. He told me, "The widely acclaimed report on the killing of the martyred intellectuals was written by Hedayet Hossain Morshed. In my journalistic career, I have never seen another reporter like him. Unfortunately, in this country, talent is not recognised, and that is why he has been forgotten today."

Shahadat Parvez is a photographer and researcher. The article is translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments